Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is reportedly considering an expansion of fighting and a “full occupation of the Gaza Strip”.

There is strong opposition to the idea from within Israel’s senior military ranks, amid growing international condemnation of Israel for the increasingly dire humanitarian disaster in Gaza. Yet Netanyahu is expected to present the plan to his cabinet to capture the last areas of the strip not held by the Israeli military, including areas where the remaining hostages are believed to be being held.

A majority of Israelis want the war to end and see any remaining live hostages returned safely. But a section of the population are preparing for the very real possibility that their dreams of resettling Gaza will be realised. Netanyahu’s decision is not necessarily driven by the same motives as the would-be settlers, but the consequences on the ground may end up aligning.

This reflects similar dynamics in the history of Israeli settlement building. Based on security rationale, successive Israeli governments have set about controlling the Palestinian population.

In the wake of military conquest, settlers have moved in to establish outposts. Gradually, these outposts have become settlements as families have flooded in, whether driven by secular Zionist ideology, encouraged by cheaper properties, stirred through religious beliefs, or inspired by dreams of a better quality of life.

The Gaza Strip was first occupied by Israel at the beginning of what became known as the “six-day war”. Responding to intelligence reports that its neighbours were mobilising against it, Israel launched a series of pre-emptive strikes against Syria, Jordan, and Egypt.

Israel Occupation of Gaza

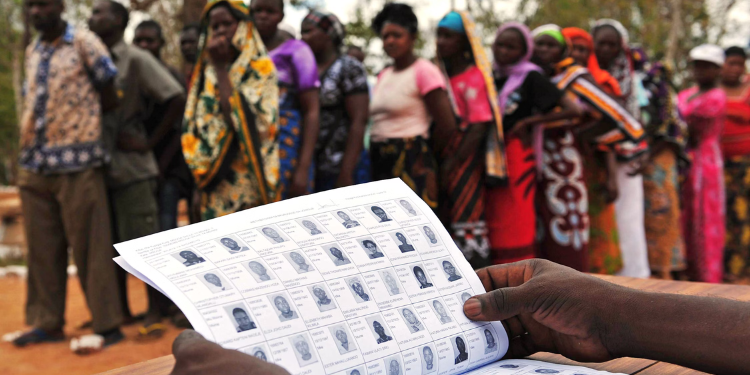

On June 5, 1967, Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Major General Yeshayahu Gavish commanded his troops to occupy the Gaza Strip, which was then under the control of Egypt.

He did so in defiance of orders from Israel’s then defence minister, Moshe Dayan, who had warned against being “stuck with a quarter of a million Palestinians” in an area “bristled with problems … a nest of wasps”.

But once it had moved IDF troops into the Strip, the Israeli government followed a policy of breaking up Palestinian-populated areas by establishing military outposts, which then became civilian settlements.

In 1970, Israel’s then Labour government established two “Nahal settlements”. Named after the Nahal brigade, founded by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, these settlements were agricultural communities established by military force. By 2005, there were 21 civilian settlements in the strip, with a total estimated population of 8,600, living alongside a Palestinian population of around 1.3 million.

The settlers’ ideology at that stage did not include the sort of racist anti-Arab sentiments that have become prolific in the ultranationalist corners of the settler movement. But the disparities between the overpopulated Palestinian refugee camps and the flourishing Israeli settlements in the Gaza Strip – protected by IDF troops – led to growing Palestinian resentment.

Also Read: UK and France Pledges Won’t Stop Bombing Gaza – But Donald Trump or Israel’s Military Could

Disengagement from Gaza

Things began to change with the second intifada (uprising), which erupted in 2000 and led to a reassessment of Israel’s settlement policy. Security considerations and a desire to reduce confrontations between the IDF and Palestinian civilians necessitated a new policy of separation.

The Israeli government also wanted to maintain a majority-Jewish population in areas under its control. So the idea of separating off majority Arab areas under the control of a Palestinian authority was appealing to the government of the then prime minister, Ariel Sharon.

Sharon had previously been known as the father of the settlement project. But in 2004, he ordered the evacuation of all Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip and four settlements in the north of the West Bank, a project which was accomplished in 2005.

The previously consistent alignment between the settler movement and the state came to an abrupt end. While the majority of Israelis supported the plan, the religious right was violently opposed.

The Jerusalem Post reported: “For Religious Zionists, who link Torah, people, and land, the state’s bulldozers felt like a theological betrayal.”

The “disengagement plan” had significant consequences on the settler movement, which then fragmented. A militant racist wing emerged, which has since grown in power and influence.

After the 2022 Israeli national elections, two of the wing’s leaders, Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, were included in Netanyahu’s cabinet. The pair have been able to use their leverage over the prime minister to influence the trajectory of the war in Gaza.

Call for Renewed Jewish Settlement

Since Israel began its onslaught in Gaza, settler groups have been calling for the resettlement of Gaza. These radicals go beyond the families that were evacuated in 2005. They include the Nachala settler organisation, whose raison d’être is establishing Jewish settlements to control the West Bank and Gaza.

The liberal newspaper Haaretz recently reported a Nachala-organised march by thousands of Israelis on July 30 to the borders of Gaza, calling for the settlement of areas of the northern Gaza Strip currently occupied by the IDF. Operational plans to establish settlements have been drawn up, and 1,000 families have signed up to reestablish a Jewish community in Gaza.

It’s not yet clear whether Netanyahu will order the full occupation of Gaza – or whether he plans to allow the establishment of civilian settlements there. But historical precedent makes this a very real possibility.![]()

Leonie Fleischmann, Senior Lecturer in International Politics, City St George’s, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.

![Senator Allan Chesang And Chanelle Kittony Wed In A Colourful Ceremony [Photos] Trans Nzoia Senator Allan Chesang With Channelle Kittony/Oscar Sudi]( https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/11/Trans-Nzoia-Senator-Allan-Chesang-with-Channelle-KittonyOscar-Sudi-360x180.png)