One day, we went to bed, as usual, and woke up to a new world. Life, as we knew it, had changed, or at least promised to change sooner rather than later.

The novel coronavirus had been reported in Africa, Egypt, to be specific, a month ago and there were concerns that it would eventually enter Kenya. On March 15, 2020, outside the President’s office, former Health Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe announced that Kenya had recorded the first case of coronavirus. The country immediately descended into a panic.

I was sitting on a bench outside Jomo Kenyatta Memorial library at the University of Nairobi when the announcement was made. The lady who was sitting next to me, whom I supposed was a student, was certainly following the announcement from her phone. When she let out a deep sigh, fidgeted and stared into the sky, I got the drift. Covid-19 was here.

Schools were closed two days later indefinitely. In those first days, we watched with disbelief as hundreds of deaths were reported in Spain and Italy. Some analysts started saying that this could perhaps be the worst spectre on the European soil since World War II. In Italy, two-thirds of the total deaths – eight of every ten associated with Covid-19 – in one week was from Lombardy, a former kingdom in the northern part of the country. In Iran, in the last week of March, one person was dying every ten minutes.

We watched on CNN and BBC as our world came to a standstill, marching to nothingness bit by bit. Many of us had not seen it like this before. From Kabul to Cape Town to New Delhi, our world was at war with a faceless enemy with whom it couldn’t negotiate. Then United States started to report more than a thousand deaths in a single day, and it all turned scary. The country that invented the internet, took men to the moon and brought them back safely was being humbled right before our eyes. Enter the lockdown. Although in Kenya we didn’t have a total lockdown, some countries like Israel and United Kingdom imposed some of the strictest lockdowns, the like of which the world has never seen.

We in Kenya were somehow lucky, lockdown remained just that: a western imagination. For a total lockdown – which some people passionately called for – meant we would grapple with the question of economic sustainability. “You cannot put hungry masses in a lockdown, that’s akin to inviting class war, “some cleaver Kenyans warned. We were worried about what would remain of our Africa if this thing entered Zimbabwe or Burkina Faso or South Sudan. If the superpowers were themselves stretched to the brink of total collapse, what would happen to us in Kenya where we spend less than 15 per cent of our GDP on healthcare? By April 2020, of the ten most impacted countries in the world, only Spain and Iran weren’t members of the G-20 – world’s most industrialized countries. By the third week of March 2020, Covid-19 had killed at least 11, 000 people globally and infected 240, 000 others.

Also Read: Post Covid-19: How Africa “Survived”

The World Health Organization immediately offered guidelines that people were expected to follow to curb the virus. One of those guidelines was social distancing. Defined loosely by Wikipedia as a set of non-pharmaceutical infection control actions intended to stop or slow down the spread of contagious disease. The idea of social distancing was to minimize disease transmission, mobility, and mortality. Experts argued that social distancing was critical in flattening the curve.

The lower the cases, the less strained health facilities would be.

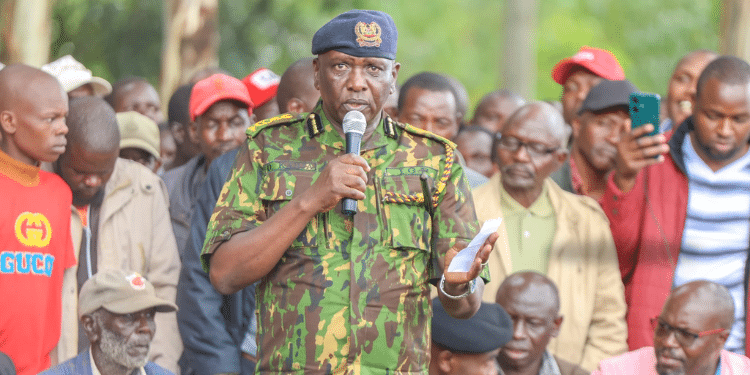

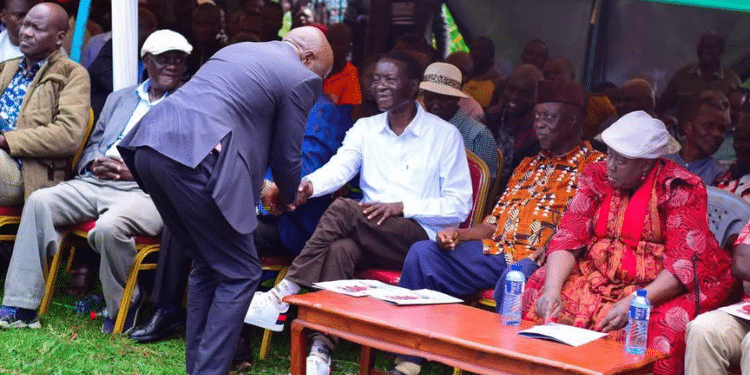

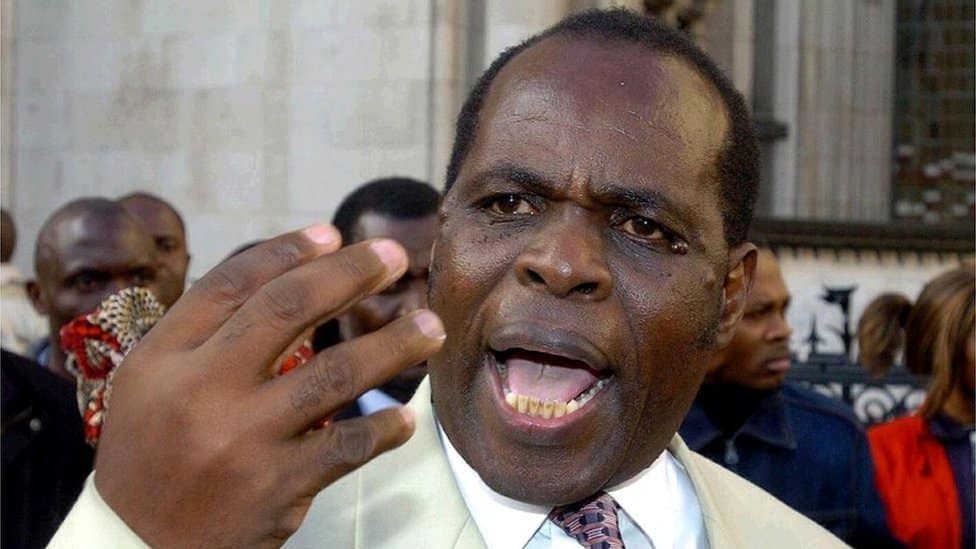

Anyone with the right conscience who had seen what was happening in Europe and the Americas would observe this guideline. Throughout the pandemic, Kenyan politicians disregarded this guideline with impunity. They held huge rallies, which turned out to be super spreaders, to advance their narrow politics at a great cost to the everyday man. When the cases surged, the government revised restrictions of movement, meaning more Kenyans lost their jobs and sources of living. The political class treated Covid-19 normally; the disease treated the people abnormally.

As Covid-19 continued to ravage the world and with calls to practice social distancing finding traction in social settings, Africa’s neglected socio-economic system was naturally exposed. In Europe, for instance, folks in lock down got their nerve from playing badminton on their balconies or hanging out on zoom and such kind of things.

Most observers raised concerns on how someone living in a squalor tin without a window in Africa can practice social distancing by staying indoors. I argued in an article published in the Standard that what was originally a health crisis could have mutated into a political one with a potential of shaking hegemony of the bourgeois elite. “Venal African leaders have modelled Africa into a progressively unequal society in which social prestige, honor, precedence, and authority is overwhelmingly acceded to the rich. And the people have but revered this system,” I noted.

Where they’re expected to build modern hospitals for sustainable health care they engage in populist acts like clearing hospitals bills for patients as they fly their families abroad to access better services. When they’re elected to amend the economy, they steal and grab everything and anything. And where they’re elected to reorganize social systems, African political leaders have created class barriers that discriminate on the basis of material wealth.

Due to this selfishness, social and economic systems in most African countries have historically remained unconscious of the plight of the poor majority. As much as rapid response is important in flattening the curve, the truth is lockdown was a western imagination that would not stand the test of time in Africa.

In case of a complete lockdown, Africa’s lower-class majority would mobilize a revolutionary class consciousness that would pit them against the bourgeoisie minority. In this way, people who live from hand to mouth, who fear the lockdown more than the disease, would not be able to go to work to earn the Sh200 that they use on food. One in three Africans lives below global poverty line. And, according to African Child Policy Forum, nearly 60 million children in Africa do not have enough food despite the continent’s economic growth in recent years. If push came to shove, the proletariat would have tempted to rob from the rich. This would ignite an unprecedented political problem that no country was prepared to deal with, at least as of that time.

The impact of an ideologically unpopular and selfish foundation on which the idea of Kenyan nation-state rests was best felt during those difficult, uncertain times when politicians went out of their way in interpreting the law in the context of their own choosing. The lack of sense of guilty with which Kenyan politicians disregarded Covid-19 health protocols is the stuff of “caste arrogance”: A type of arrogance that, as was as the case in the nineteenth century Europe, must only come from the “desired elements’ in the society. The Kenyan idea was and remains a fragile society that even the most innocuous things could finish off; leave alone a pandemic that brought humanity to its knees at an unprecedented speed. Everyone knows that Kenyan health care system is underfunded and unsustainable. Everyone knows that Kenyan political leadership is corrupt and awfully inept.

Everyone knows that Kenya, like most global south countries, is proudly unequal.

When former Nairobi Senator Johnson Sakaja announced that he was resigning from Senate ad hoc committee on Covid-19, some Kenyans congratulated him for being accountable. Sakaja had initially been charged with violating Covid-19 containment measures and, upon pleading guilty, ordered to pay Sh15, 000, which he did without straining a nerve. But ordinary Kenyans didn’t have the luxury of being presented before a court of law.

From March to July 2020, when the country went into a partial lockdown, most, if not all, cases of extrajudicial killings were connected with the same rules that the good lawmaker – now the Nairobi governor – violated. By the time Covid-19 arrived in Kenya, the country was already a deeply unequal society operating within a semi-constitutional structure. This partly explains why the country struggled to fight the virus as “one people”.

In such times of great uncertainty, the foci of the political class, ordinarily, ought to have been on how to rejuvenate the economy, which was already doing poorly pre-Covid. But that wasn’t the case.

By June, in western Kenya, where political dance had started unusually early, practical politics were at the zenith, with the group allied to the President Uhuru and opposition leader Raila Odinga being allowed to hold meetings while the one affiliated to the then deputy president William Ruto denied opportunity.

Kenyan unique economic situation demanded that the government responded uniquely. As the living condition of the average Kenyan worsened day by day due to movement restrictions, the government found itself between a rock and a hard place. “It is a question of lives versus livelihood,” one commentator observed. It was about confronting what Marxist geographer and anthropologist David Harvey called pre-existing cracks and vulnerabilities in the hegemonic economic model. Despite scientists warning that the search for a medicinal vaccine would be a protracted and chancy process, Kenyan government demonstrated ineptitude as far as making ‘social vaccine’ – non-pharmaceutical measures like social distancing to contain the spread of the virus – effective was concerned.

“If you tell people to practice social distancing in the market, for example, it’s only logical and honest that you provide extra locations that are accessible and sustainable without which people will invariably disregard such directives,” I wrote in The Star.

I posed the question: If a vaccine would not be available until after the next 15 months, what happens to a people living in a troubled economy like Kenya’s? For how long is the government going to ask them to stay at home? Or continue to restrict their movement?

However, I noted, that when all had been said and done, it was not inherently the government’s role for a ‘social vaccine’ to be effective. That called on every citizen.

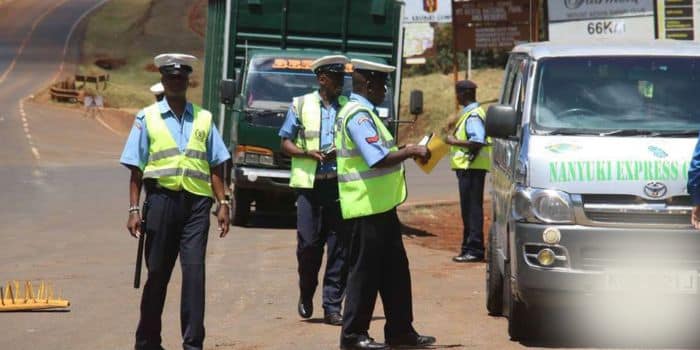

When it came to enforcement of movement restrictions, the state of the relationship between Kenyans and their government came to a sharp focus. In a classical colonial fashion, the government packaged its message in a militant language and tone in the hope that it would inspire discipline. A draconian law was signed by President Uhuru Kenyatta that would see those caught without wearing a face mask fined Ksh 20, 000.

It was possible to convince people, through aggressive sensitization, to wear masks or try staying at home as much as they financially could without forcing them. The moment the government introduced the fine, and declared war on its people, the majority started wearing masks for the police, to avoid arrest.

That’s why some put it below the chin, not necessarily to keep safe from the virus but from the often-violent police. This showed that the language used by the government was ineffective. “Why frame a public health emergency as a war? Leaders tend to like the war metaphor because it grants them the necessary authority and legitimacy to declare a state of emergency enforce exceptional measures and mobilize their resources to achieve their objectives,” Marwan Bishara, a senior political analyst with Al Jazeera, wrote.

War metaphor had been significantly used in the fight against the new coronavirus across many countries including in the U.S and U.K. But it is in Vietnam where the metaphor was taken quite literally with the military assuming the central role; supervising food supply in the community and coordinating accommodation in quarantine facilities.

While the war metaphor could be used by leaders to acquire necessary authority and legitimacy, as Bishara righty notes, in Vietnam it produced tremendous results with the country registering one of the best testing ratios in the world, at the time.

It was clear that Vietnam had learnt from previous health emergencies, like the SARS of 2003 and the Swine flu of 2009 – that infected at least 394, 133 people in Asia and killed 2, 137 others. As of April 30, 2020, Vietnam had tested 261, 004 people out of which only 271 people were found positive – It was not clear if the figures represented the number of samples tested or the number of people tested.

No Covid-19 death had been recorded in the country at the time. Kenya, on the other hand, had tested 25, 145 people as of the same date out of a population of 47.56 million people. Vietnam has a population of 95.54 million people, almost twice the population of Kenya.

Success in Vietnam, a middle-income economy with a GDP per capita of slightly less than $3,000 (as of December 2019) was attributed to a number of factors; high level of openness, timely response and measures that resonate with the people such as use of popular artists to create awareness. Whilst compulsory wearing of masks was imposed in the country immediately the first two cases were reported, on January 28, the enforcement was not violent as was the case in Kenya.

Public negligence, excessive sloganeering unaccompanied with logical measures and lack of aggressive contact tracing was the story of Covid-19 in Kenya.

Most observers raised concerns over the transparency of the Kenyan government in its response to the pandemic. Dagoretti South Member of Parliament, for example, took to Twitter to rant on what came out as a deliberate misguidance of the public by the government on the true situation in the country with regard to Covid-19. In times of crisis, when humanity is faced with a common existential enemy, people naturally turn to their leaders for assurance and direction.

When the Promised Land wasn’t forthcoming, the Israelites channeled their apprehension to Moses, whose great leadership skill is frequently used as an accepted reference. In the nineteenth century Europe, when Hitler was keen on implementing his “Jews must be exterminated like bedbugs” philosophy, the Jewish society, as dysfunctional as it was, relied on its educated elite for hope. Lack of openness on the side of the government served to perpetuate denialism among some Kenyans. “I don’t know of anyone who has been infected with this disease,” one Kenyan in Kericho said. This distrust, evident among most Kenyans especially in the rural areas, caused majority to abstain from the test.

The openness of the Vietnamese government in its endeavor to contain the virus has largely been informed by previous popular revolts where the people expressed their dissatisfaction with some of the government policies, as was witnessed in 2016 when Vietnamese took to the streets over mass fish poisoning. Why the Kenyan government was slow to learn from its past mistakes on policy implementation was a bit difficult to understand.

Why it still chose to communicate in a language heavy on violence, intimidation and subtle coercion was baffling.

Every time the Kenyan government communicated to the people on the virus, it almost always did so in a coercive and mechanical way. But that was not surprising. Use of police force to achieve government agenda has slowly become a social convention in Kenya. Kenyan state has history of adopting neo-colonial posture on virtually everything it does.

Whether it is the teachers demanding an increase in allowances or the health workers calling for implementation of a Collective Bargain Agreement signed some years ago, the government’s language has been unavailing on most occasions. In consequence, a national disconnect naturally develops between the ruled and the rulers, which hinders solidarity that any form of concerted effort calls for especially in times of crisis.

The young man who was assaulted in Nairobi’s Kahawa West in May 2020 by the police for allegedly breaking curfew order did not stay at home the following day because WHO advised people to stay at home as much as they could. He certainly stayed at home to avoid a similar experience from the police.

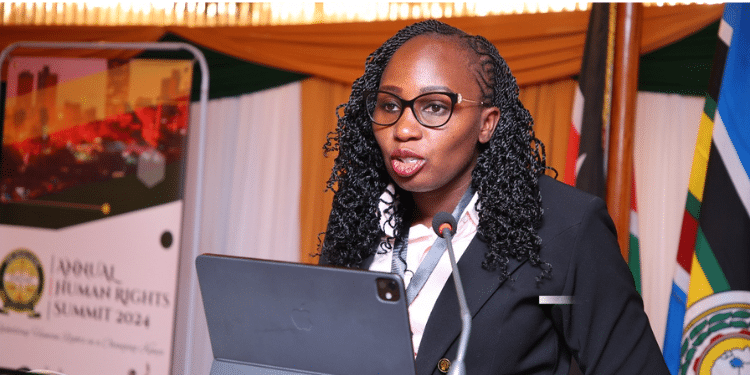

Dialogical communication and non-violent language would be critical in handling the pandemic. To end stigma, for example, more information about the virus was needed to increase people’s knowledge about it. That could not be achievable with the use of gun-toting police officers.

For people to understand Covid-19 as a disease whose containment called for individual and community responsibility it was important to use dialogical communication approach rather than a coercive, military-style approach. This would have enhanced smooth flow of information and community solidarity. Containing the spread of the virus remained a big challenge because people at the community level didn’t take relevant measures in order to protect themselves from the virus; instead, they did so to avoid arrest.

As Covid-19 cases continued to rise exponentially, the monstrous inequality in the Kenyan healthcare system was brought into sharp focus. The pandemic occasioned unprecedentedly difficult times that hit most households off the top of their heads. “We are going through the darkest period in post-independence history which could see our ravaged economy get on the skids,” one columnist wrote.

Companies furloughed their employees. SMEs went under. And a consuming uncertainty hung over many households. As a result, governments across the world were desperately racing against time to cushion their citizens against the effect of Covid-19 pandemic.

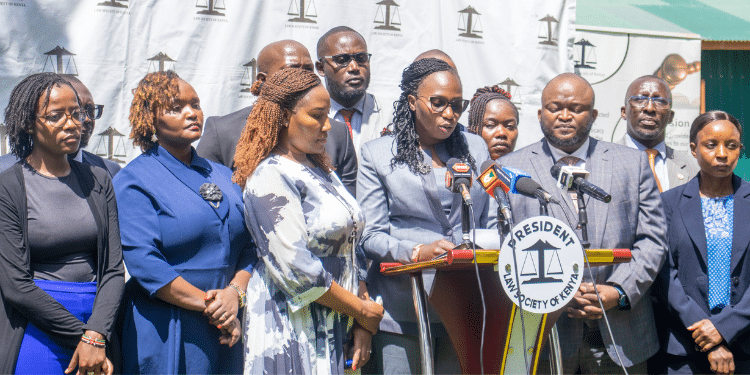

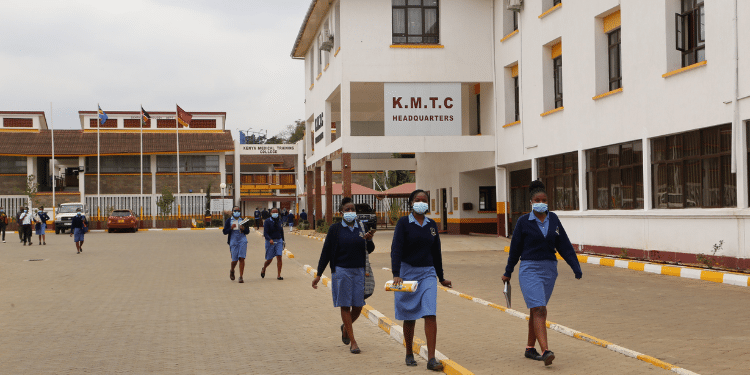

Inadequately funded, under stuffed and neglected, there were fears that Kenya’s public healthcare system would be stretched to breakdown in the worst-case scenario. In April 2020, nurses announced that they would go on strike if that is what it would take for the government to address their grievances. To defuse the imminent crisis, the government said it had an elaborate plan on how to fix the situation; nurses therefore suspended the industrial action to give room for dialogue. Four months later, little had been done. Nurses issued another strike notice.

“There is no government in this country,” one Kenyan wrote on Twitter. Kenyan state has a tendency of playing a cat-and-mouse game with health workers which rasies serious questions of governance. Why is the government slow in addressing pertinent issues around public health? In a leadership forum in May 28, 2020, Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union acting Secretary General Chibanzi Mwachonda said the welfare package promised by President Uhuru in his address to the nation had not been unveiled, more than a month later.

Kenya’s health care system, like United States’, is increasingly market-oriented making it highly discriminatory against class. Because it’s capitalist, it’s also exploitative. The end of communism three decades ago marked the triumph of capitalism, the system that saw at least 0.001 per cent of world’s population earn 350 times the wages of average workers. Kenyan founding fathers chose capitalism over socialism; the newly independent Kenya grew into extremely unequal society where national wealth was concentrated on the hands of a few people.

The inequality created corporate greed that dominates every capitalist system hence dividing the county between two classes: the bourgeoisie (also the political elite) and the proletariat (average workers).

With the need to transit from production of goods to provision of services, the bourgeois-led corporations turned services such as health and education into private enterprises with sole purpose of making profit.

The bourgeoisie leveraged its proximity to – if not possession of – political power to change the laws such that public servants could do business with the government. The Ndegwa report of 1971, for example, served to legalize this project. The bourgeoisie used its wealth to control the government, means of production and its economic policies, thereby seizing away essential services such as health and education from government’s control.

With an unlimited demand, privatization of health care has become a lucrative business and a vicious market in which profit-making is the cardinal law.

Capitalism naturally discourages the creation of an affordable and sustainable public health care system for the simple reason that demand for private health care would decrease, hence profit would plummet. This partly explains why Kenyans might not have a functioning public health care just yet as long as the capitalist bourgeoisie are allowed to run the show.

In September 2020, Ethics and Anti-corruption Commission established that public procurement laws have been flouted in the award of tenders by Kenya Medical Supply Authority, the body mandated to purchase and distribute medical resources in Kenya.

The anti-corruption agency confirmed that public money had been unlawfully spent on the purchase of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and other medical supplies. Kenya had received close to $2 billion from Jack Ma’s Alibaba Foundation International Monetary Fund, World Bank and World Health Organization to help in the fight against Covid-19. Run-away corruption and greed in the Kenya’s health sector meant health workers in the front row were exposed to the deadly virus as they attempted to save lives. At least 1,000 doctors had been infected with coronavirus as of the first week of September. Ten others had died.

Kenya had initially targeted to test at least 250,000 people by the end of June 2020, 66 days after the first case was reported. By May 17, just 15 per cent – 38,000 – of the target had been tested. 78 days after the first case was reported, Kenya had tested less than 70,000 samples and/or people.

Ineptitude, systematic corruption and lack of correct information on the virus contributed to the low testing rate recorded.

As Standard’s Mercy Korir and Daniel Wesangule reported, Kenya had the capacity to test more people than it did, thanks to generous donations from Chinese billionaire Jack Ma.

But it couldn’t because it was ill-prepared.

The Jack Ma and Alibaba Foundation did three rounds of donations to Africa. In the first round, Ethiopian Airline helped distribute the equipment consisting of: 20,000 laboratory diagnostic test kits 1,000 protective suits and face shields, to each of the African Union Member States. On April 6, an announcement of the second round of additional medical sullies to all the fifty-four countries was made.

These included five hundred ventilators, 200,000 sets of protective clothing and face shields, 2,000 thermometers, one million swabs and extraction kits, and 500,000 gloves.

In the third round, according to African Union, the donations included 46 million masks, 500,000 swabs and test kits, 300 ventilators, 200,000 sets of protective clothing, 200,000 face shields, 2,000 temperature guns, 100 body temperature scanners and 500,000 pairs of gloves.

From these, if equally distributed, in donations Kenya should have received 27,000 swabs and 18,000 extraction kits. Added to the 6,000 diagnostic and sample collection kits in Kenya Medical Supplies Authority’s possession and 200,000 testing and sampling tubes from China, testing ought to have been seamless.

National Nurses Association of Kenya Baringo Branch Chairperson Elizabeth Yatar told Daily Nation on May 19, 2020, that some of their members were not aware of the basics of handling coronavirus patients or how to take care of themselves. “We are perturbed to hear claims by Governor Kiptis (former Baringo governor) that isolation wards had been set up at the region’s major hospitals. Where are those wards? We are yet to see any. Health workers have not been trained on the infection preparedness as he (Kiptis) claims,” she said.

As Covid-19 pandemic permeated the structures of human society, bringing with it a new normal, humanity united. Or at least there was a need to do so.

People came to terms with the reality that there was more that united them than divided them.

In Kenya a sense of what Ngugi wa Thiong’o called peoplehood found traction easily in the society. A group of women from Tala, Machakos County, for more than two months, offered food for police officers manning roadblocks, erected to head off movement in and out of Nairobi metropolitan area. These women noticed that the officers could not access food due to the remoteness of their location, and as good people, they decided to cook for them.

This incident was beyond doubt a strong act of faith in humanity. Come to think of it; it came from the very people who have been at the receiving end of police violence in Kenya. Just a month earlier, police in Kisumu teargassed traders at Kibuye market in Kisumu, vandalized their wares and injured some in what was supposed to be enforcement of social-distancing rule.

Many a times when we talk about police brutality and extrajudicial killings in Kenya, it’s the common people we’re talking about.

Put into context, the relationship between the Kenyan State and the average Kenyan has not been up to snuff since the police department was established. Contemporary Kenyans have found themselves in – or rather created for themselves – a system characterized by political and moral anarchy where impunity, corruption, lawlessness, and greed are the major indictment.

Lack of proper order in the government together with arrant unwillingness to live up to true hallmarks of leadership is the reason why Kenyans’ happiness, as Plato prophesied in the Republic, remains unassured. Even if they were do their part better than they have already.

When everyone was talking about the new normal: The regeneration of life as we have known it, I found myself thinking more about the functionality of the Kenyan society. How is the Kenyan project going to be like post coronavirus? I was imagining, perhaps prematurely, a concerted attempt to reorganize the Kenyan society. I was thinking more about the emergence of national urgency to uphold fundamental laws of effective social relations and political engagement.

All those rules of life that we have paid no heed to before. I was thinking about a different new normal. Maybe I was wrong.

My wish was to never see Kenyans undergoing social ostracism. My greatest wish was a new normal that would mark the end of black apartheid. The “when are we returning to normalcy question” didn’t resonate with me as much as it did with my peers. I was more concerned about the type of normalcy we would return to.

I believed there was need to initiate a narrative, deep inside our consciousness, to live a better life than we have lived. A productive, just and honest life where we collectively put out accumulated knowledge to the service of humanity and the society. My greatest wish was a new normal that would reclaim the humanness we have lost while unlearning the selfish, self-serving habits we have committed our lives to, for a very long time.

My utopic reflections were cut short by disturbing news on racial discrimination in parts of China. Black people in Changzhou, China had been whisked out of their homes, denied access to hotels and basic amenities for allegedly spreading the virus. It was clear the fight against Covid had taken a racist turn. Although first reported in Wuhan, the origin of Covid-19, as I was researching this piece, remained unknown. However, there is no indication that it could have originated in Africa.

Therefore, to blame Africans for its spread was racist and uncalled for. It was strange listening to Kenyan foreign affairs affairs principal secretary Macharia Kamau trying to excuse this egregious violation of human rights. “Africans, Kenyans alike, have been discriminated against in the process of the provisional government’s response to trying to mop up the situation they are facing there post the crisis they had in the last few months,” he said.

By announcing that Kenyans marooned in China and elsewhere would be evacuated at their cost, the Kenyan state was yet again reminding it citizens that it wasn’t unable to fail in its most primary function: To defend its citizens.

In the week that followed this development, I wrote the following in an op-ed that was not published:

We not only have a government that is struggling with a legitimacy problem, but one that is also dysfunctional. This government has failed to fulfil its core functions in the past. And, as we know, it is used to relying on the veil of nationalism and ethnic solidarity to conceal its monstrous and violent character.

When Nation Media Group editorial director Mutuma Mathiu was economical with the truth on the matter, I sent him the following email:

Dear Mutuma,

First and foremost, Kenyan State didn’t whisk Kenyans in Changzhou from their homes, denied them access to basic amenities and committed grave human rights abuse against them. The Chinese authorities did. Second, as you appreciate, sometime in February, the Kenyan State allowed an airplane with 234 passengers aboard from China – then the epicentre of the virus – to land at JKIA, in what remains a fundamentally treacherous decision by the government of Uhuru Kenyatta. Suffice it to say that the Chinese have no moral ground to accuse people of African descent (that you fail to identify as such) of spreading the new coronavirus. This middle-of-the-road journalism, Mr Mutuma, I think, isn’t enough nowadays.

To expect a morally bankrupt and systematically corrupt government to function properly in the face of a pandemic is like asking someone who believes in the immorality of the soul to share in the administration of the State. Plato noted in his masterpiece The Republic that it is the moral speculation that would bring glory of humanity into contempt.

From the moment it was created, the Jubilee government decided to rule with violence and impunity. By choosing to pursue self-preservation – through BBI, which the courts declared unconstitutional – with earnest affection than wisdom, Uhuru Kenyatta demonstrated his inability to rise to the challenge of personal example. Of course, he couldn’t attain the character of personal truth that is the hallmark of true leadership that’s critical in responding to a global (health) crisis, for instance.

Before his death, according to Christian account, Jesus was heard saying; “it is finished”, (John 19:30). These words are normally used by Christians in times of adversities or in relevance to the difficulties of this life as affirmation of faith and victory. As Kenyans of faith turned to Jesus to provide for them during those unheard-of times, they were equally asking themselves where their politicians were. The latter had gone silent in a way that worried Kenyans but one which wasn’t supposed to. Kenyan Politicians are difficult characters to understand. One day they’re God’s chosen ones with whom He is pleased, if Kenyan political theology is anything to interpret, the next day they are vicious individuals of easy virtue ready to acquire and preserve political power at all costs.

In ordinary times, the heart of the Kenyan political class whirls on a static gyre of practical politics. But the pandemic didn’t come with ordinary times. Most politicians were literally ‘in it together’, with the people. But Kenyan politicians have never been most politicians. In the face of those strange times, they were indulging in an outburst of politics of self-preservation characterized by greed and callousness.

Four points were stark on the behavior of Kenyan politicians during the pandemic: First, we’re not equal before the law. Textbooks tell us that the law promises more than it can deliver, because:

(a) The law is always a work of political imagination.

(b) While the law is authored either by politicians or individuals with politicians’ interests at heart, it is meant for the everyday people. Selective enforcement of Covid-19 guidelines during the pandemic validates this point.

While ordinary Kenyan people were arrested and charged and sometimes beaten to death for allegedly violating some these guidelines – restriction of movement, mandatory wearing of face masks, and social distancing among others – politicians violate them with impunity.

Second, human dignity doesn’t matter to Kenyan politicians. Covid-19 pandemic exposed Kenyan politicians as self-seeking individuals who are ready to trade human dignity for public likability. Most of the items that politicians donated, be it a small bottle of hand sanitizer or a face mask, had their name or picture emblazed on it. While the act of giving is good, it can be used to extract public likability.

Public sympathy can be utilized to defeat justice, as was the case with the ICC cases in which a section of Kenyans hawked prayers for the six Kenyans, among them the current president, indicted for crimes against humanity when in real sense it was victims of their alleged actions who ought to be prayed for.

Third, Kenyan politicians perpetrate the endemic culture of impunity in Kenya. In April 2020, Dominic Cummings, a top adviser to the former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, violated a lockdown rule that restricted movement in and out of London.

Although he didn’t resign, he provided concrete reasons that prompted his action before offering a lengthy apology. In Kenya, political leaders violated Covid guidelines with neither compunction nor presence of mind to apologies.

Fourth, Kenyan politicians don’t respect the social contract that they have with them. One journalist argued in a TV talk show in March 2020 that the political elite was calling for a lockdown essentially because they feared that people living in the informal sector could spread the disease to their neighborhood. As far as Kenyan politicians are concerned, the everyday man is only important during elections after which any service offered to them is purely out of favor.

It’s difficult to imagine the magnitude of loss humanity could have faced assuming the outbreak of Sars-Cov-2, the virus that causes covid-19, happened in 1500, when, as Yuval Noah notes in Homo Dues, people lived their lives knowing that some infectious disease would annihilate them in one swoop without being able to do anything. Covid-19 had killed 6.55 million people as of October 4, 2022. The virus was first reported in Wuhan, but, as we have said, whether it originated from there is yet unclear.

This would probably have been the case three centuries ago. Take the case of “black death” that started in 1330s, around central Asia. From Yuval’s account, a flea-dwelling bacterium called Yersinia pestis infected humans bitten by the fleas. In less than twenty years, the plague had spread all over Asia, Europe and North Africa.

Between 75 million and 200 million people are believed to have died.

In England alone, the human population dropped from 3.7 million to 2.2 million people.

Apart from mass prayer meetings and processions, which clearly didn’t work, people were defenseless. Like other diseases that erupted at that time, “black death” was blamed on angry gods, malicious demons, or bad air. “People readily believed in angles and fairies, but they couldn’t imagine that a tiny flea or a single drop of water might contain an entire armada of deadly predators”, writes Yuval.

But “black death” isn’t the worst plague that has beset humanity thus. A small Spanish flotilla that left Cuba for Mexico on the afternoon of March 5, 1520, carrying 900 Spanish soldiers and a few African slaves would become the source of smallpox virus. By December of that year, the virus had killed an estimated eight million Mexicans.

Population of Mexico dropped to less than two million people 60 years later as a result of deadly waves of flu, measles, and other infectious diseases. When “doctors” and priests were consulted, they advised prayers, cold baths, and other strange remedies like smearing squashed black beetles on the sores. Excessive religiosity didn’t solve the situation, again. Remember this was at the tail end of middle age when popes still ruled Europe and the Pharaohs could still lord it over the Egyptians.

People died like chicken in tens of thousands because of lack of medical intervention. The “Spanish flu” of 1918 infected, within a few months, a third of the global population –some half a billion people. The First World War killed at least 40 million in four years, the “Spanish flu” killed between 50 million to 100 million people in less than a year. You get the picture?

Today, unlike with the 1330s folks, we can rely on a vaccine or treatment to stamp out deadly diseases. We’re lucky Covid-19 pandemic struck in this day and age of scientific revolution. At least 1.17 per cent of the world population – some 91.6 million people – had been fully vaccinated against Sars-cov-2 by March 18, 2021.

Just three decades ago, HIV was a death sentence; doctors debated if patients were even worth saving. Today, an African man (HIV disproportionately affected Africans) is more likely to die from malaria or TB than HIV, thanks to recent milestones in medical research.

Soon after Kenya confirmed its first Covid-19 case, the government had acknowledged, like most global south countries, that to reckon with the pandemic, its response would be different from those of developed countries.

Social inequality, among other factors like high cost of living, meant the government couldn’t impose a snap lockdown, as some experts had argued, to flatten the curve and get back to normalcy in the shortest time.