It’s tariff season again, with the next deadline looming on Friday, August 1. Since the beginning of July, the United States has issued another flurry of tariff announcements, revising the sweeping plan announced on April 2. Back then, the Trump administration threatened to apply so-called “reciprocal” tariffs of up to 50% against many trading partners, plus an eye-watering 125% on Chinese imports.

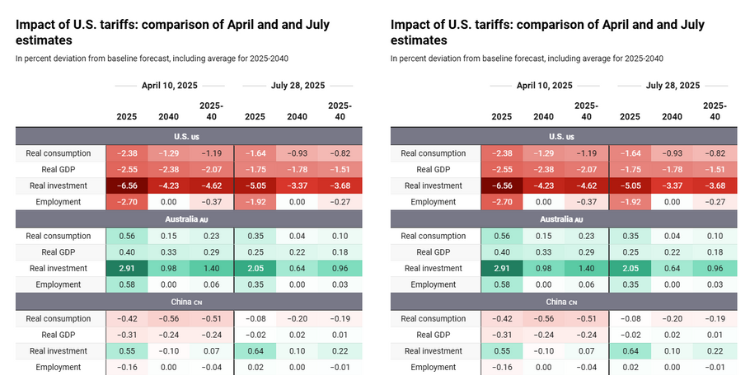

In April, we modelled those measures, together with retaliation by trade partners. We reported they could cut more than 2.5% from US gross domestic product (GDP), reduce US short-run employment by 2.7%, and cut US real investment by almost 7%.

In the wake of those “Liberation Day” tariffs, financial markets took fright. On April 9 the Trump administration hit pause: the “reciprocal” tariffs were deferred until July 9 and replaced by an across-the-board 10% tariff increase, with a handful of exceptions.

Trump Trade Deals

Even so, the Trump tariff drum kept beating. Duties on steel and aluminium were doubled to 50%, and copper was swept in with its own 50% rate. Washington announced some “trade deals” with:

• United Kingdom – dropping the UK rate to the base rate of 10%

• China – cutting the tariff to 34%

• Vietnam – reducing its “reciprocal” tariff from 46% to 20%

• Japan – a 15% levy on all imports, including motor vehicles (otherwise tariffed at 25% for other regions)

• European Union – just announced at the weekend, reducing its “reciprocal” tariff from 30% to 15%.

When the first pause expired this month, a second extension pushed the start date for the “reciprocal” tariffs to August 1. But the tariff announcements keep coming, with recent threats to apply revised tariffs on imports from many trading partners, including a 50% tariff on imports from Brazil.

Also Read: How Europe Plans to Respond to U.S. Tariffs in 2025

What do the New Tariffs Mean for the Economy

To find out, we reran our global economic model with the US tariff schedule as it stood on July 28, again allowing trading partners to retaliate proportionally (excluding Australia, Japan and South Korea, which have ruled out retaliation). This table compares the April projections with the updated results.

Damage to the US economy is less severe, but still substantial. In 2025, the falls in: real (inflation-adjusted) consumption narrow from a decline of 2.4% to 1.6%; real gross domestic product (GDP) from a fall of 2.6% to 1.7%; and real investment from a slide of 6.6% to 5.1%.

For the US, lower tariffs on the EU, UK, Japan, Vietnam and especially China, mean less disruption to short-run employment and long-run capital markets, lower efficiency losses in product markets, and less punishing retaliation from abroad.

Beijing also benefits from Washington’s climbdown. Short-run losses in Chinese real consumption shrink from 0.4% to 0.1% in 2025, and the GDP loss all but disappears. Cutting the US tariff on Chinese goods to 34%, and the corresponding pullback in China’s retaliatory duties, explains most of the improvement.

Australia is Still a Winner – But Less So

Australia remains a beneficiary, but to a lesser degree. In April we projected short-run gains of 0.6% in consumption and 0.4% in GDP. These are now more modest, with a gain of 0.3% and 0.2% respectively. Two forces lie behind the downgrade:

1. Australia’s relative tariff treatment has narrowed. In April, Australia faced a 10% base tariff while many of our trade competitors in the US market confronted much higher “reciprocal” rates. Many of those have now been cut, eroding the relative price advantage of Australian products in the US market.

2. The global investment diversion is smaller. When investment contracts in the US and in regions relatively hard-hit by US tariffs and retaliatory action, some investment is reallocated to more lightly hit economies.

Because the projected fall in investment in the US and other regions is now milder, the corresponding investment inflow to Australia weakens, with our forecast boost to Australian investment dropping from 2.9% to 2.1% in the short-run.

Also Read: Disappointed Trump Shortens Ceasefire Deadline for Russia’s Putin

What Should Canberra Do

For the moment, the tariff outcomes still tilt slightly in Australia’s favour. That hardly argues for rushing into concessions in a bilateral “deal of the week” with Washington, let alone making unilateral concessions outside of any bargaining framework. This is especially true when US policy continues to appear reactive, volatile and unreliable.

However, the source of Australia’s edge is fragile.

As the US pares back its own tariff threats against other countries, the relative price advantage Australia enjoys of being subject only to the 10% base rate will diminish, and so too will the investment diversion effect.

Hence, a further US retreat from high and differentiated tariffs may yet expose Australia to net economic harm. That point has not arrived, but it may be on the horizon as US tariff policy evolves.![]()

James Giesecke, Professor, Centre of Policy Studies and the Impact Project, Victoria University and Robert Waschik, Associate Professor and Deputy Director, Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.