At Nairobi’s bustling Muthurwa Market, 34-year-old Mary Wanjiku begins her day at dawn, arranging tomatoes and onions on a rickety stall. By evening, she has paid multiple levies market fees, security charges, and informal “compliance” costs to county askaris. Her profits shrink to a mere fraction of what she hoped for.

“I sell to survive, but it feels like I work for the county,” she laments. “Every shilling is taxed, yet I don’t see the benefits.”

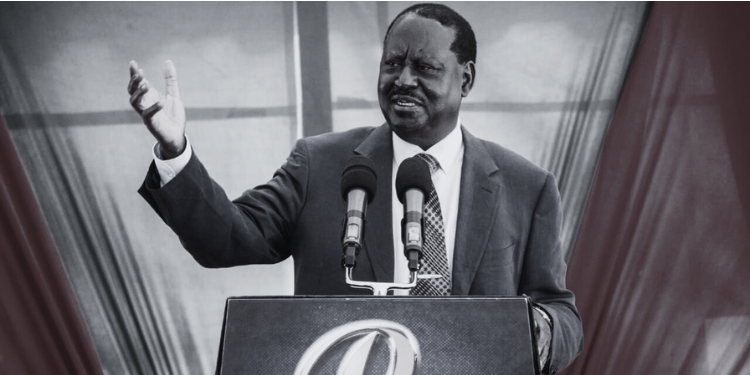

Mary’s experience is shared by millions of informal traders across Kenya —small business owners who form the backbone of the economy yet carry the heaviest tax burden. For decades, the late Raila Amolo Odinga championed their cause, calling for progressive taxation —a system in which those with higher incomes contribute more, ensuring fairness and inclusion for all. His stance on taxation was never about opposing taxes but about promoting justice, equity, and dignity for ordinary Kenyans.

When Taxation Becomes Oppression

Raila consistently argued that Kenya’s tax structure had become punitive rather than developmental. He warned that increasing taxes without addressing corruption and inefficiency would only breed resentment and evasion. “When you increase taxes, people will evade them,” he said bluntly. To him, raising taxes on essential goods like bread, cooking oil, and maize flour while offering generous loopholes to elites was “cruelty disguised as taxation.”

His words resonate with the findings of the National Taxpayers Association (NTA), which recently launched a campaign for inclusive taxation. The NTA urges both national and county governments to adopt progressive tax measures that ease the burden on women, youth, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and persons with disabilities (PWDs).

Also Read: Babu Owino Pens Glowing Tribute to Raila Odinga Amid ODM Succession Fireworks

“Kenya’s tax system doesn’t favor those at the bottom while rewarding those at the top,” says Patrick Nyangweso, CEO of NTA. “Women in informal markets, youth entrepreneurs, SMEs, and PWDs are paying more than their fair share. That is not fiscal justice it is economic exclusion.”

SMEs and the Forgotten Majority

Kenya’s SMEs employ the majority of citizens and sustain families across the country. Yet instead of nurturing them, the tax system suffocates them with multiple levies and complex compliance demands. A boda boda rider in Kisumu or a hairdresser in Umoja often pays more proportionally than a multinational corporation shielded by sophisticated tax lawyers.

“Our SMEs are suffocating under levies designed without their realities in mind,” says Nyangweso. “If we want them to grow and employ more Kenyans, taxation must be progressive

and fair.”

Raila echoed this sentiment throughout his political life. He believed that taxation should expand opportunity, not extinguish it. His approach was to broaden the tax base by empowering growth, rather than punishing productivity. He urged the government to seal corruption loopholes, formalize the informal sector, and simplify compliance procedures arguing that efficiency, not excess, was the path to fiscal stability.

Persons with Disabilities: Left Behind by the Taxman

While Kenya has some of the most progressive disability laws in Africa, implementation remains poor. A new NTA study shows a troubling gap between awareness and access to tax benefits for Persons with Disabilities (PWDs).

“Almost 80 percent of PWDs know tax incentives exist, but fewer than 40 percent have ever applied,” explains Tom Onditi, the researcher who led the study. “The barriers are not about motivation they are about systems that are too complex, centralized, and unfriendly.”

Many PWDs describe the application process as tedious, expensive, and humiliating. Some must travel long distances just to be certified. Even those with permanent disabilities must renew their tax exemption certificates every five years. “Why must I prove I am still disabled when my condition has no cure?” one respondent asked.

The shift to digital platforms like eCitizen has worsened the problem. “The system is simply not disability-friendly,” Onditi says. Older PWDs and those lacking assistive technology find the online process almost impossible.

Even when approved, some employers resist implementing exemptions, citing payroll complexities. Meanwhile, Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) officers have been accused of inconsistent application of rules. The NTA report also highlights the caregiver blind spot, families providing unpaid care for PWDs are excluded from existing tax reliefs despite bearing heavy financial burdens.

“The caregivers are the silent enablers of our society,” Nyangweso notes. “Recognizing them within fiscal policy would strengthen disability inclusion and household resilience.”

Blueprint for Fairness

Both Raila’s economic ideals and NTA’s advocacy outline a roadmap for an equitable tax system:

- Reduce VAT on essential goods to protect low-income households.

- Simplify tax filing and registration for SMEs and startups.

- Introduce tax credits for PWDs and their caregivers.

- End unnecessary reassessments for permanent disabilities.

- Decentralize medical vetting to Huduma Centres nationwide.

- Incentivize inclusive workplaces to expand employment opportunities.

- Establish tiered county fees reflecting business size and income level.

Raila emphasized that such measures would not only make taxation fairer but also rebuild trust between citizens and the state. “People will gladly pay taxes when they see honesty, fairness, and service delivery,” he said.

Accountability, Transparency, and Trust

Raila’s lifelong struggle for fiscal justice was grounded in the belief that taxation without accountability is exploitation. He criticized successive governments for overtaxing citizens while failing to deliver essential services. His vision was clear: public trust must be earned through integrity in spending.

Also Read: Raila Rests: The Unhealthy State of Affairs He Leaves Behind

At the county level, Nyangweso echoes this view. “It makes no sense for a woman selling vegetables in Muthurwa to pay almost the same as a supermarket chain. Revenue collection at the grassroots must be fair and accountable.”

When taxpayers see fairness and transparency, compliance increases naturally. But when corruption flourishes, tax evasion becomes a form of protest.

Countries like South Africa, India, and the United Kingdom offer models of progressive fiscal reform. South Africa exempts assistive devices from VAT, India provides tax holidays for startups, and the UK integrates gender-sensitive budgeting. These policies not only reduce inequality but also boost productivity, proving that progressive taxation is both ethical and practical.

A Legacy of Equity

For Raila Odinga, taxation was not just an economic instrument; it was a test of justice. He envisioned a Kenya where fiscal policy uplifts the weak, not burdens them; where paying tax is seen as an act of shared nation-building, not coerced survival.

As the NTA’s report concludes, “We cannot talk about inclusion if our tax system locks out people with disabilities.” The same could be said of any Kenyan struggling under an unfair tax regime.

Raila’s voice may have fallen silent, but his message rings louder than ever: a just tax system is one that leaves no one behind.

Mary Wanjiku, the market woman in Muthurwa, and thousands like her are not asking for charity—they are demanding fairness. They are asking for a Kenya where taxes build hope, not hardship. And that, as Raila would have said, is the true meaning of freedom.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates