This year’s event stretches 8,549 km over 15 days of racing, including a four-day excursion into the yet unexplored desert dunes of the vast Rub’ al-Khali, or Empty Quarter.

“‘Be Afraid’ seems to be the message of the route for the 2023 Dakar,” said organizers when they revealed the course at the start of December.

The warning does not appear to have put anyone off: more than eight hundred riders, drivers and co-drivers will set off in an array of motorcycles, cars, quads, trucks, and light vehicles when the race begins on Saturday.

Among them are some well-known names, including nine-time World Rally champion Sebastien Loeb (BRX) who is relishing the prospect of competing in his sixth Dakar.

“It’s 14 stages, it’s very long, a proper endurance rally,” he said. “We need to find the right pace to get to the finish with as few mistakes as possible.”

The Frenchman, who has just won the 2022 edition of the Extreme E, has a tough battle in front of him if he is to improve on his three podium finishes and chalk up that first win.

Notably, he will need to unseat defending champion Nasser Al-Attiyah (Toyota), a quadruple winner of the event, but he will also be up against another WRC legend Carlos Sainz (Mini) as well as the Dakar great Stephane Peterhansel (Audi) who has won the event fourteen times — eight in a car and six on a bike.

On the motorcycle side, defending champion Sam Sunderland (GasGas) will face a stiff challenge from the likes of Daniel Sanders (GasGas), Pablo Quintanilla (Honda), Matthias Walkner (KTM) and Adrien Van Beveren (Honda).

Concerns

This year’s race takes place against a backdrop of concerns linked to Saudi Arabia’s human rights record and military intervention in neighboring Yemen.

That ongoing war has left hundreds of thousands of dead, and millions displaced, with a large part of the Yemeni population close to famine, according to the United Nations.

Last year, preparations were rocked by an explosion two days before the start of the race which left French driver Philippe Boutron seriously injured.

An “accident” according to Riyadh, although French investigators concluded in February that the explosion had been caused by an improvised explosive device.

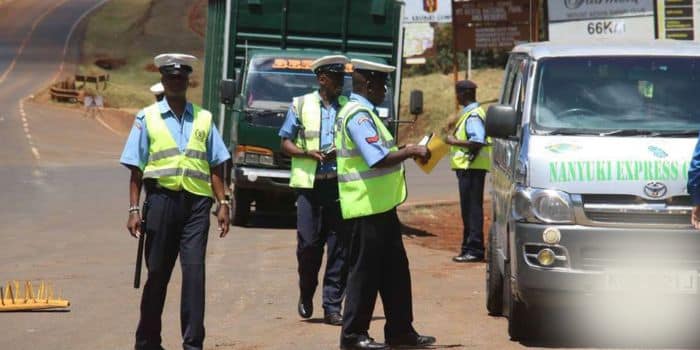

Amaury Sport Organization, which runs the event, says it has increased security around the bivouacs where the 2,700 people of the Dakar caravan will be accommodated.

The rally, of course, is no stranger to security issues.

The first race in 1978 set off from the Trocadero in Paris and ended in the Senegal capital but after 29 years in Africa, the threats became too great.

That meant moving the race to South American for 11 years before switching it to Saudi Arabia in 2020.

Since then, it has come under the spotlight of NGOs criticizing the “sport washing policy” of the Arab world’s largest economy.

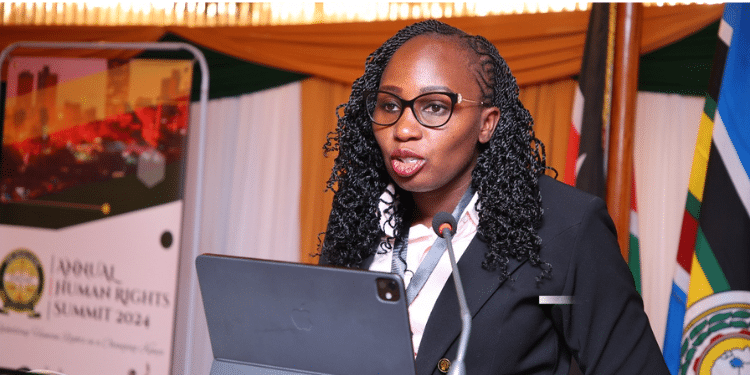

“Sports fans should not indiscriminately believe the image fabricated and presented by the Saudi government through these events,” said Joey Shea, Saudi Arabia researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The NGO documented “widespread human rights violations in the kingdom, including arbitrary arrests of peaceful dissidents and human rights activists, some of whom were sentenced to decades-long prison terms simply for posting on the social media,” she said.

A host of other sports have, like the Dakar, shelved any such concerns, with high-profile football, cycling, Formula E, Formula One and boxing events all having been staged in the country.

The rally ends on January 15 on the kingdom’s eastern sea border.