Would you trade your privacy and freedom for safety?

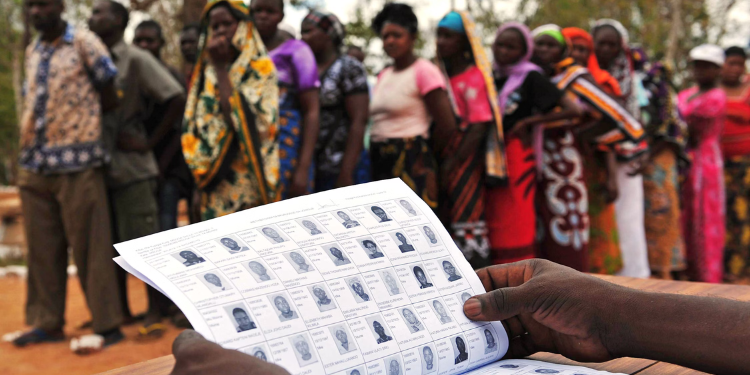

If you are a Kenyan, you already have. With CCTV cameras, facial recognition, and biometric IDs or commonly known as the Huduma Namba, integrated into everyday life, Kenyans are already living in the digital age of policing, whether we like it or not.

However, when the county government of Nairobi unveiled the “Safe City” project about 10 years ago, in collaboration with Huawei Enterprise, residents were promised that more cameras would lead to less crime.

Now, with almost 2,000 CCTV cameras keeping a constant watch, the streets do not feel any safer. Crime has not disappeared, but privacy slowly is.

Investigations by Coda Story reveal that transparency around the system is minimal. For instance, who controls the footage, who gets access, and how it is actually used remain unclear.

Technology that can make our streets safer, our police more efficient, and our justice system harder to manipulate. But if left unchecked, the same tools meant to protect us could be used to watch us, track us, and even silence us.

Also Read: Man With Police Handcuffs Nabbed in Nairobi CBD Crackdown on Criminal Gangs

The Surveillance History of Kenya

According to a report by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), surveillance in Kenya has deep roots in colonial intelligence networks that were designed to control populations instead of protecting them.

Today, that can be seen through CCTV on city streets, digital police records, and biometric systems like Huduma Namba, yet the government still lacks laws that regulate surveillance directly. Broad constitutional provisions and the 2019 Data Protection Act are being stretched to cover new digital realities, according to the IDS Report.

Furthermore, the IDS warns that if Huduma Namba were integrated with private sector data like telecoms or banks, it could evolve into Kenya’s most powerful surveillance tool with few legal safeguards against abuse.

An academic study by the East African Nature and Science Organization (EANSO) on the ethical implications of surveillance in Nairobi notes that although technologies like CCTV and facial recognition can help in crime prevention, they also raise significant ethical concerns.

However, they come with risks of breaches of privacy, insecure data storage, and the potential misuse of personal information.

This implies that Kenya is embracing surveillance technology faster than its ability to regulate it.

Also Read: Albert Ojwang: Technician Reveals He Was Paid Ksh3,000 to Delete CCTV Footage

Is Kenya Using Technology as a Tool for Justice or Fear?

Digital tools can empower citizens just as easily as they can empower the state.

A study in the Reviewed Journals International highlights how social media has become a powerful way to expose police misconduct through videos of brutality being spread rapidly to force accountability.

However, the same platforms are monitored by security agencies to track dissenters.

Kenyans hesitate to report abuse for fear of being targeted themselves most of the time, according to the journals.

Additionally, within the police service, the digital transformation is mixed. The use of digitized Occurrence Books (OBs) has reduced lost case files and strengthened accountability.

But according to a ResearchGate report, without proper ethical training, officers could easily manipulate these digital records as they once did with paper files. Therefore, technology is only as trustworthy as the people and systems behind it.

The East African Journal of Law and Ethics notes that although digital policing can improve efficiency, it can just as easily be weaponized against citizens.

What Smart Surveillance Looks Like for Kenya

Smart surveillance is not about installing more cameras or digitizing more records.

It is about designing a framework that ensures technology serves security while protecting the freedom of the people.

Consequently, the government, through the parliament, should pass specific surveillance laws that define what data can be collected, how long it is kept, and under what circumstances it can be shared.

The East African Journal of Law and Ethics makes a similar case: technologies like facial recognition and data integration can strengthen policing, but without strong oversight, they risk breaching privacy and enabling misuse of citizens’ personal information

Additionally, surveillance must not be left only in the hands of the police or the executive. An independent body should oversee its use, conduct audits, and report to the public regularly to build trust. The Institute of Development Studies (IDS) report warns that Kenya lacks a dedicated surveillance law, instead relying on broad constitutional provisions and the Data Protection Act.

The centralization of data under the Huduma Namba system, especially if merged with private-sector databases, could create Kenya’s most comprehensive surveillance regime (IDS, Surveillance Law in Kenya).

Further, surveillance works best when citizens are part of the equation to promote collaboration instead of coercion. When people feel ownership over security tools, they are more likely to trust and use them.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.

![Senator Allan Chesang And Chanelle Kittony Wed In A Colourful Ceremony [Photos] Trans Nzoia Senator Allan Chesang With Channelle Kittony/Oscar Sudi]( https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/11/Trans-Nzoia-Senator-Allan-Chesang-with-Channelle-KittonyOscar-Sudi-360x180.png)