In the early 1950s, a quiet but consequential standoff unfolded between Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) over the baptism of his children, including Raila Amolo Odinga.

The dispute, rooted in the naming conventions imposed by Christian missionaries, would escalate into a rare confrontation between African tradition and colonial religious authority.

Jaramogi, a staunch advocate of African identity, had written to a local priest requesting baptism for his children.

He insisted they retain their Luo names, rejecting the European Christian names traditionally required by the church.

The priest refused, citing church policy that mandated names like “Aggrey” or “David” for baptism.

Unwilling to compromise, Jaramogi escalated the matter to the Church Missionary Society’s leadership.

Church Missionary Society Intervenes

Archdeacon Alfred Stanway, a senior figure in the missionary hierarchy, consulted the bishop in Nairobi.

After deliberation, the bishop ruled in Jaramogi’s favor, stating that African names were acceptable for baptism and that the church had no theological basis to reject them.

Despite the ruling, no African priest was willing to defy convention and perform the baptism.

In Not Yet Uhuru, Jaramogi recalled:

“Church zealots of the day thought I was insane when I insisted that my three eldest sons, be baptised with the names of local community heroes.”

The resistance reflected the deep entrenchment of colonial norms within local church leadership, even in the face of official approval.

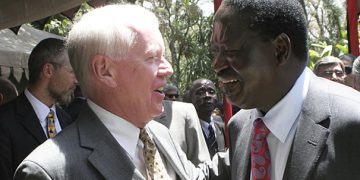

European Priest Steps In

Even Jaramogi’s wife initially refused to participate.

She saw no point in attending a ceremony that had already rejected her children’s names and, by extension, their identity.

Her absence was a silent protest against a church that demanded cultural surrender in exchange for spiritual inclusion.

Jaramogi didn’t wait.

He found a European priest willing to baptize his children without altering their names.

The priest baptised Ng’ong’a Molo Oburu, Raila Amolo Odinga, and Ngire Omuodo Agola—names rooted in Luo heritage, not European scripture.

The baptism was very discreet.

Jaramogi, then principal at Maseno Veterinary School, enlisted his students to assist with preparations.

His wife entered the church only at the last moment, allowing the ceremony to proceed.

This act of defiance was more than a personal victory as it challenged the church’s monopoly on naming and identity, and it set a precedent.

Raila would later write:

“Although people had at first thought him very strange, many later followed suit and baptised their children with African names.”

The unnamed priest did not become a public figure. He did not make headlines.

But his willingness to act where others hesitated made him a quiet enabler of cultural resistance.

No Word from England

Contrary to popular retellings, there was no directive from England.

Also Read: Profile of Winnie Odinga: Education, Career, Family and Net Worth

The decision was made locally by church leadership in Kenya.

While the CMS was a British institution, the ruling came from the bishop in Nairobi after consultation with Archdeacon Stanway.

Raila Odinga’s Religious Life

Unlike many Kenyan politicians who use religion as a campaign tool, Raila rarely invoked scripture or church platforms for political gain.

He attended church regularly, especially Anglican services, and maintained close ties with clergy.

Also Read: Raila Odinga’s Final Message to Football Fans Before His Death

Those close to him, including clergy, often described him as a man of quiet devotion.

Bishop Kodia, in his funeral sermon, said:

“I saw in him a man who had made peace with God in everything that he said and everything that he did.”

Raila also supported interfaith dialogue, appearing at Muslim and Christian events without bias.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.