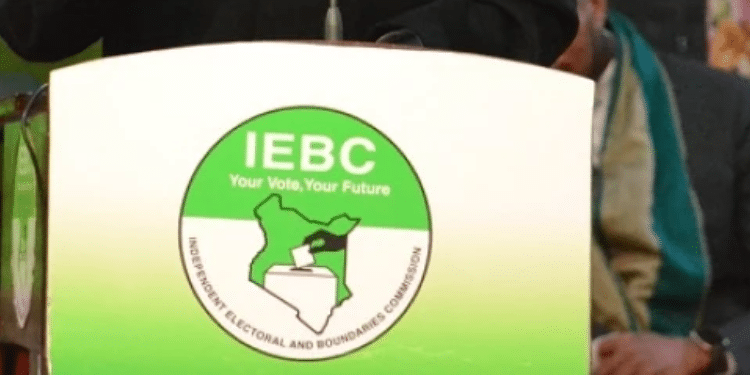

A central pillar of Kenya’s democracy, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) is tasked with the monumental responsibility of delivering free, fair, and credible elections, operating at the intersection of law, data, and public accountability.

Yet, beyond ballot boxes and vote tallies lies a broader mandate that shapes representation, influences resource distribution, and affects the daily lives of Kenyans in subtle but powerful ways.

But what exactly is the anatomy of the IEBC? How does its design influence national policy, governance, and accountability?

What are the critical tasks that define its mission, especially following the enactment of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (Amendment) Act, 2024?

Understanding the role of the IEBC in electoral delimitation

Among the most far-reaching functions of the IEBC is electoral delimitation — the process of redrawing and reviewing constituency and ward boundaries to reflect population shifts and ensure fair representation.

Delimitation is anchored in Article 89 of the Constitution, which mandates the IEBC to periodically review electoral boundaries so that each Kenyan’s vote carries equal weight.

In 2024, Parliament passed an amendment to the IEBC Act that significantly restructured this delimitation process, introducing timelines, transparency obligations, and strict oversight mechanisms aimed at restoring public trust and legal clarity.

Under the new law, the delimitation process must follow a five-phase structure. The Commission begins with a preliminary phase in which it announces its intention to review boundaries and publishes a preliminary report.

This report must contain the proposed names and boundaries of each constituency and ward, classification of areas (such as urban or rural), the population figures used, and the mathematical formulas applied to determine these boundaries.

Also Read: European Ambassadors and High Commissioners Affirm Support for New IEBC

This publication serves as the basis for public engagement. Public participation is no longer optional or symbolic.

The amended law requires the IEBC to carry out extensive public education and conduct hearings in every county. Kenyans are invited to submit their views — whether oral or written — and the Commission must consider all feedback in compiling a revised report.

This revised version is then tabled before both the National Assembly and Senate, which have a maximum of 14 days to make recommendations.

Importantly, the IEBC is not bound to accept all the parliamentary input, but it must consider it carefully before preparing its final report.

Once the final report is ready, the Commission must publish it in the Kenya Gazette. If the Government Printer fails to gazette it within seven days, the IEBC is permitted to publish the report in at least two newspapers of national circulation, which will have the same legal effect.

This clause is particularly significant as it shields the Commission’s independence from bureaucratic interference.

If any Kenyan is dissatisfied with the final delimitation, they may file a judicial review case at the High Court — but must do so within 30 days of publication.

This window ensures prompt legal redress without stalling the implementation of the Commission’s work.

Reliance on the census

Another major change is the reliance on the most recent national census data to inform boundary reviews.

This move underscores a shift towards evidence-based policymaking, where demographic realities, not political negotiations, determine representation.

Constituencies must, as nearly as possible, match the population quota — calculated by dividing the total population by the number of constituencies.

This is a step toward correcting imbalances where some MPs represent less than 50,000 people while others serve more than 200,000, creating disparities in development allocation and political influence.

The law further mandates that all records of the delimitation process — from hearings to formulas — must be documented, transcribed, and archived for public access. This transparency requirement enhances public confidence and allows citizens, researchers, and the media to scrutinize the Commission’s work.

Additionally, any public officer who unlawfully delays the gazettment of the Commission’s report now faces criminal liability, including imprisonment for up to one year.

This introduces a level of accountability rarely seen in Kenya’s bureaucratic processes.

To support this complex task, the Commission can now compel cooperation from other public institutions. The Ministry of Interior, the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), the Department of Surveys, and other state departments are legally obligated to provide data and technical support.

How IEBC Affects policies, governance and accountability

This ensures that the Commission’s decisions are not made in isolation but are backed by authoritative national datasets and expert input.

The cumulative effect of these reforms is a more transparent, accountable, and data-driven Commission.

For ordinary Kenyans, this means that their voices must now be heard during boundary reviews, that their areas will be classified and represented based on actual population data, and that any attempts to delay or sabotage the process will be met with legal consequences.

Also Read: IEBC Denies Claims of Mass Voter Registration in North Eastern

For policymakers, it means embracing a governance structure where fairness is not an afterthought, but a legal requirement.

And for the IEBC, it is both a burden and a badge — a test of whether it can deliver on its constitutional promise under tighter scrutiny and higher expectations.

New leadership sworn in

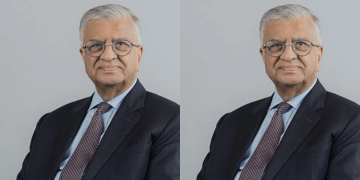

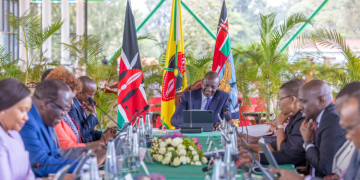

The new IEBC Chairperson, Erastus Ethekon, on Friday, July 11, alongside six commissioners, were sworn into office to serve a six-year term, at an event held at the Supreme Court Buildings.

The other commissioners are Vice-Chairperson Fahima Araphat Abdallah, Ann Njeri Nderitu, Moses Alutalala Mukhwana, Mary Karen Sorobit, Hassan Noor Hassan, and Francis Odhiambo Aduol.

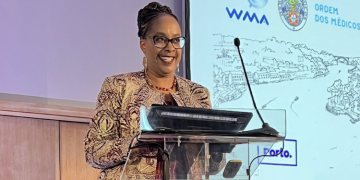

The swearing-in ceremony, which was presided over by Chief Justice Martha Koome, paved the way for the seven to formally assume their IEBC roles.

It came after President William Ruto, in two gazette notices dated July 10, 2025, formally regularized the commission’s appointments process following a recent High Court ruling.

In his maiden speech after taking over as the IEBC Chairperson said he is honoured by the trust placed in him to lead the commission, which is vital to the country’s democracy.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.

![President Ruto Address During Mashujaa Day And How He Honored Raila [Full Text Speech] President Ruto Address During Mashujaa Day And How He Honored Raila [Full Text Speech]](https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/10/ruto-mashujaa-address-360x180.jpg)