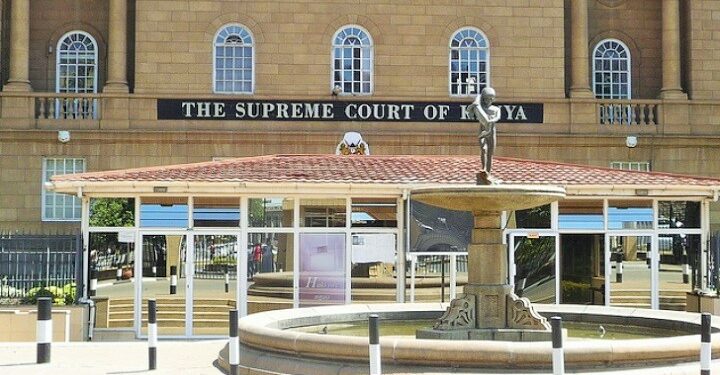

In Kenya, the court system operates under a hierarchical structure, including superior courts: the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal (COA), and the High Court. Subordinate courts, such as Magistrates, Kadhis, Courts-Martial, and others established by legislation, complete the system.

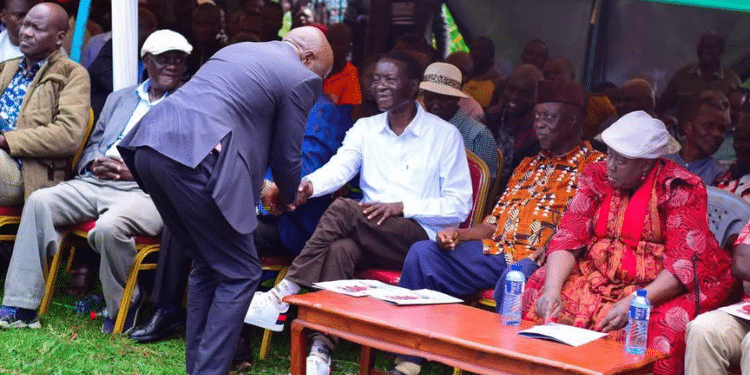

The Chief Kadhi, holding the same status, privileges, and immunities as a High Court Judge, presides over the Kadhis’ Court. A crucial role of this Court is determining inheritance rights for non-Muslims and children born out of wedlock to a Muslim father.

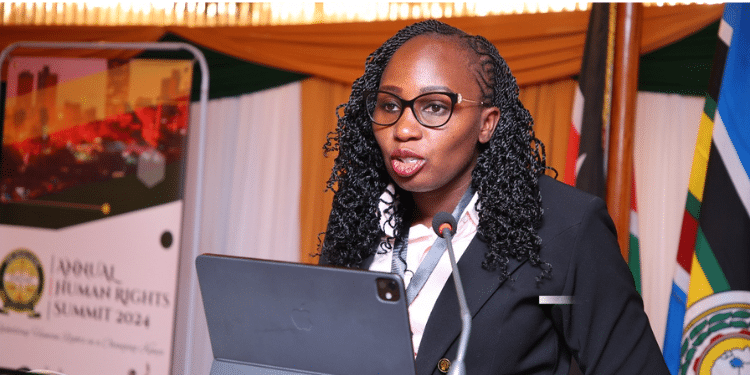

The Kenyan judiciary has extensively explored human rights concerns arising from Islamic inheritance laws, with an ongoing evolution in legal understanding. In re Estate of CCBH (Deceased), the High Court examined the constitutionality of provisions in Islamic law that exclude “illegitimate children” and their non-Muslim mothers, who were not married to the deceased Muslim father, from inheriting. The central issue was whether these provisions were discriminatory based on religion and violated property rights.

During the case hearing, evidence showed that the young children depended on their father for support. The applicants invoked regional and international human rights agreements upholding equality and fairness. The Court, in 2017, determined that the Kenyan Constitution does not guarantee an absolute right to equality. Additionally, it recognized that Kenyan law lets Muslims distribute their assets solely according to Islamic law.

Thus, under Kenyan law as it is, “illegitimate” children and non-Muslims are not entitled to inherit from a deceased Muslim.

While sympathizing with the children, the Court held that the responsibility ultimately lies with the deceased and the children’s mother, who knew that the applicants were not recognized as heirs under Islamic Sharia. To avoid such situations, provisions should have been made for the children through a will. Khadhi courts generally respect the freedom of Muslims to create a valid will and allocate at most one-third of their estate to non-heirs.

Although the Kadhi’s Court has consistently enforced the law’s provision that assigns women only half of what men receive from their deceased fathers, circumstances were quite different in Ramadhan Mustafa vs. Zulfa Ngasia Juma. In 2019, the High Court addressed whether daughters who had married Christian men and changed their names could inherit from their father’s estate. The Kadhi’s Court had earlier denied their acknowledgment as legitimate heirs. It prompted the High Court to examine whether this decision violated Article 27 of the Kenyan Constitution, which prohibits the denial of rights based on religion.

In the High Court decision, it was held that the provision of equality under Article 27 is qualified by Article 24(4). It thus allowed the application of Muslim (Sharia) law in matters of personal status, marriage, divorce, and inheritance before the Kadhi’s courts. Consequently, the Court affirmed that the daughters could not inherit from their father, confirming the correctness of Kadhi’s Court decision.

This ruling clarifies that non-Muslims, including children and relatives, cannot inherit from Muslims. It aligns with previous case law where the High Court determined that non-Muslims and “illegitimate” children can only inherit from their mothers, not their fathers.

In 2018 in the CKC & Another v. ANC, the Court of Appeal addressed whether children born to a Muslim father and a non-Muslim mother, who were not formally married, could inherit from their deceased father’s estate. The lower courts ruled that Islamic law applied, excluding non-Muslim children born out of wedlock from inheriting. The children argued that Islamic law did not apply to them as non-Muslims and that the Kadhi’s Court lacked jurisdiction over the matter. The Court of Appeal largely agreed with them. However, the Court did not address the repugnancy and constitutionality of the Islamic inheritance law.

According to the Kadhi’s Court’s interpretation of Kenyan inheritance laws in the context of Islam, two significant human rights concerns arise.

First, while the Kadhis court acknowledges the freedom of Muslims to distribute their estate through testamentary provisions, a potential concern arises from the limitation that restricts non-heirs to receive only up to one-third of the estate and assigns women half of what men receive from their deceased fathers. Restricting the amount that can be bequeathed to legitimate female heirs and non-heirs (including illegitimate children) undermines individual freedoms per testation principles. Besides, it limits individuals’ ability to provide for or gift their loved ones according to their preferences or level of need.

Second, this restriction undermines the principles of equality and non-discrimination. By denying persons born out of wedlock the right to inherit from their fathers (in the absence of a will), their fundamental human rights are violated. These individuals did not have control over the circumstances of their birth and should not be disadvantaged based on factors beyond their control.

In conclusion, the inheritance laws pertaining to women and children born out of wedlock in Kenya raise significant human rights concerns. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensuring the protection of human rights and promoting a more fair inheritance legal system.