The future of journalism is grim, experts hold. Media organizations world over, including the established ones, are grappling with far-reaching financial challenges that have led to mass reorganizations.

Like their counterparts in other countries, Kenyan journalists have been impacted by the post-pandemic shift in business media environment, triggering a conversation on who owns the media and how can media organizations survive in these difficult times.

Apart from The Standard newspaper, only Daily Nation sells at least 60,000 copies daily. On February 21, 2022, the latter provided fresh fodder for the Kenya punditry mills with its headline: “Why is he still in office?”

The editor wondered why the then Deputy President William Ruto – now president – was hanging around Harambee House Annex, the office of the deputy president, despite having gone “rouge”.

Most Kenyans, particularly those on Twitter, called out the editor for what they described as “brown-envelope journalism”. “Kenyan journalism is crappy,” one Kenyan wrote. Another one added that Kenyan mainstream media is compromised.

Most journalists will tell you that journalism is not exact science. Journalists sometimes actually take sides and sometimes, if not most of the time, they get it wrong.

A friend of mine, a veteran newspaper commentator and university lecturer, asked me to read Who Owns the Media? at the backdrop of this debate.

I read the book and filed a brief report titled “the mythology of the free press in Kenya”. We might like to talk about journalism generally and Kenyan journalism in particular in the most liberal, refreshing manner, but the truth is there is no such thing as fully independent journalism in a market-driven media system.

The media system in Kenya, as is pretty much the case across the world, is controlled by capitalist, corporate forces whose biggest interest is maximization of profit.

Ownership structure of a media house usually defines its editorial independence, or lack of it. Equally, ownership structure defines the level of political and commercial interference that permeates the newsroom.

Mr. Victor Bwire, the Director, Media Training and Development at the Media Council of Kenya, says media houses should adopt business models that are financially sustainable.

In his powerful essay titled The Mythology of the Free Press in the United States, media scholar Robert McChesney notes that: the question is not whether the government plays a role in establishing media and communication systems, because it plays a foundational role.

The question is: in whose interest and for what values are government policies in communication meant to encourage.

Most people argue that as long as the government keeps its hands off the media, a society’s flow of information and ideas will be safe. It is uncommon to come across more nonsense in a single sentence than in what you just read: because who is the government?

The government is essentially the coterie that wields political power and systemically endeavors to manage the lives of the people.

In Kenya, the powerful forces in the media system are either politicians or are eminence grises who enjoy proximity to the political leadership.

Since the political elite own the media system in Kenya, as we have said, our journalism increasingly serves the interests of that clique. If anything, professional journalism is a stenographer to those in power.

Kenyans have two options. One, mobilise resources to establish an independent media system that is fully funded by the public. That way, we can demand the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth from our journalists.

Two, make peace with the fact that our media system primarily serves the interests of the capitalist, corporate forces that control it.

A senior journalist who recently lost his job, reportedly due to the ongoing reorganizations in the media industry, told me some media houses are taking advantage of the financial situation to settle scores with its staff. “They can do better,” he says.

Ideal journalism is free, liberal and progressive. It is important for us to understand that Kenyan journalism is not ideal journalism. Our journalists, strictly speaking, serve the political and commercial interests of the media houses that employ them.

Freedom of speech

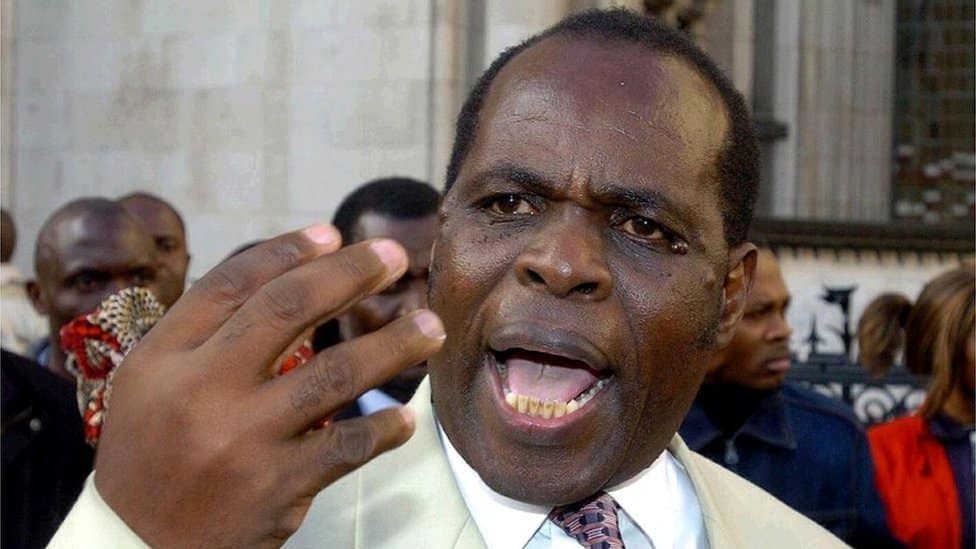

In 2018, David Mugonyi, the spokesman of the then Deputy President William Ruto, was caught on an audio recording, threatening Justus Wanga, Daily Nation reporter, in what became the fifth attack on a journalist that year.

Before that disturbing incident, there were four reported cases of violence visited on Peter Warutumo and Sammy Lutta, both of Nation Media Group, Phillip Ekadeli of Radio Maisha and Hesborn Etyanga of Radio Africa Group.

A total of 93 cases of threats, harassments and physical attacks against journalists had been reported in the previous two years – 2016 and 2017 – alone, raising grave concerns among journalists and media practitioners on the future of media freedom in Kenya.

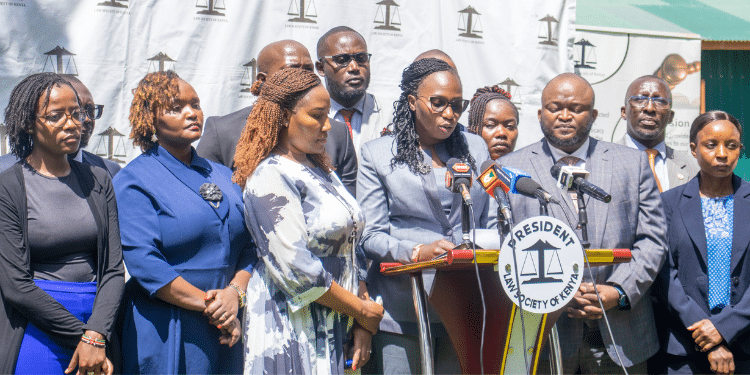

Recently, Baraza Media Lab, a co-creation space for media practitioners, in collaboration with Law Africa, launched a simplified Media Law Handbook for journalists in Kenya.

The publication, described by Judge Kathurima M’Inoti of Court of Appeal and Appellate Division as “magisterial and timely”, provides an elaborate guide for journalists on how they can and cannot practice their craft as far as the law is concerned.

“The philosophical underpinning of freedom of speech and how that freedom sits with the freedom of the press calls for revelation,” the author, Joseph Kihanya, a media law practitioner, submits.

“The idea that a public servant can insolently threaten an employee of a private company with sacking purely because of a story that he is not pleased with means that editorial independence is under attack and that for survival most journalists may resort to self-censorship of conveyor belt journalism to please those in power,” Henry Maina, a media law expert and a former member of the Media Complaints Commission of Kenya argues.

Voice of consciousness

A journalist is traditionally seen as the nation’s voice of consciousness. Their work, as Russian playwright Aton Chekhor puts it, is not to solve problems but simply to present them correctly. But journalism, as we have said, is in itself not an exact science.

In those instances when journalists commit mistakes, or are seen to have done so, depending on the nature of mistakes in question, they risk running into problems with the law.

Judge Kathurima notes in the foreword: It is from this background that laws regulating media practice world over are enacted. “In the colonial period, laws of sedition, national security and public order, incitement, censorship, civil and criminal defamation, as well as harsh regulation of the printing press, virtually destroyed the core of freedom of expression.

Even after independence and the entrenchment of freedom of expression as a constitutional right, a perverse and authoritarian state ill-drafted and overtly broad exceptions to the guaranteed freedom of expression, opaque and arbitrary licensing procedures and continued enforcement of colonial anti-expression laws, combined to ensure that free expression was as illusionary as it was in the colonial period.

Also Read: George Magoha’s Tenure at The Ministry of Education Was Horrendous…Refreshing That It Has Ended

Kenya has made huge strides in the fight for freedom of expression. Some four decades ago, the government could jail, sometimes without trial as was the case of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, dissenting voices at will.

When it didn’t agree with what a particular media house was doing, government officials could walk in a newsroom, vandalize equipment before arresting journalists. That is not the case today. We, as one panelist put it during the launch of the Handbook, have come to birth.

The 2010 Constitution made sweeping changes to the law as we had experienced it before by introducing important guarantees on freedom of the media under article 34.

The revolutionary constitutional guarantee bars the state from “exercising control over or interfering with any person engaged in broadcasting, the production or circulation of any publication or the dissemination of information by any medium, penalize any person for any opinion or view or the content of any broadcast, publication or dissemination.

Though not a legal advice, as the author warns the reader, the Handbook puts into context the place of the law in media practice and why it is important for anyone who engages in the practice of journalism at whatever level to understand the same.

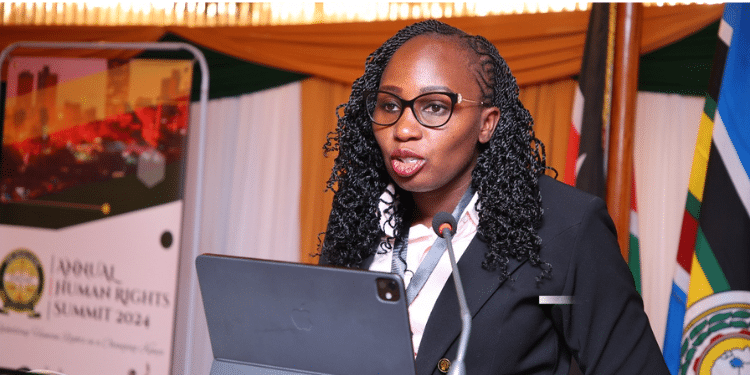

The handbook comes at a time when the conversation around data protection is mainstreaming. The 1948 United Nations on Declaration of Human Rights, under article 19, entitles everyone to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media, regardless of frontiers.

The advent of new media has turned virtually everyone with a smartphone into a journalist. Social media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Twitter are slowly replacing traditional media platforms such as newspapers through what has come to be known as “citizen journalism.”

If there was a time when progressive laws governing media practice were necessary, it is now. “Laws on many aspects of media law and practice are in an ever-changing paradigm. The practice of journalists is changing as this environment changes,” the Handbook observes.