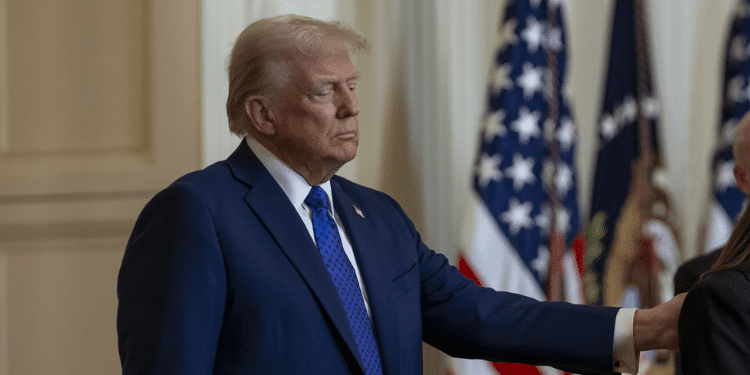

Greg Garrett is a former humanitarian deckhand turned global advocate for healthy food systems.

After sailing remote seas with Mercy Ships in the ’90s, he now leads high-level conversations with investors, governments, and corporations about food and nutrition equity as the Executive Director of the Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNi).

His mission is to put people’s health and nutrition at the heart of global food policy.

Backed by the Gates Foundation and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), ATNi holds the world’s biggest food companies accountable for what ends up on our plates.

In East Africa, that mission is urgent. A silent shift is reshaping diets in Kenya and beyond. Traditional meals are giving way to processed, sugary, and salty packaged foods, even in rural areas.

According to Greg Garrett, malnutrition has not disappeared; it has evolved. Today, undernutrition exists alongside rising obesity, diabetes, and other noncommunicable diseases. Garrett sees this as a chance for the region to course-correct before it follows the same dangerous path as Western nations.

In this conversation with The Kenya Times’ Joy Kwama, Garrett unpacks the nutrition crisis, the rise of silent obesity and other non-communicable diseases, and why East African companies and governments must act now to protect future generations.

How would you describe the current state of health and nutrition in Kenya? In your view, what are the most pressing challenges the country is facing in this space?

When I first started coming to Kenya in 2012 with different organisations, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiency were more severe than it is today.

I think Kenya has done a good job of influencing micronutrient intake. There are still issues, for sure. But now that there’s a mandatory fortification program for wheat flour, edible oils, and iodised salt. We are seeing more and more people getting the necessary vitamins and minerals.

But at the same time, since 2012, I have seen a difference. And that is in the urban and peri-urban areas, where people are consuming more and more unhealthy packaged foods, which are often too high in fat, sugar, and salt.

You can see that modern food retail is also providing more and more packaged food options. And of course, that’s convenient for people, but it’s not very healthy.

I think the big challenge now for Kenya is to continue to do the good work on undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies. But that has been going better than the other problem, which is growing obesity, growing diabetes, and overall growing noncommunicable diseases.

In fact, when the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) produced its State of Food and Nutrition Security Report in 2023, the report showed that many countries in Africa, including Kenya, now have higher populations at risk of becoming diabetic.

Until now, often these reports would just focus on hunger and undernutrition issues.

And for the first time, we’re seeing that these reports are saying that it’s not just among the wealthy in Africa, this problem exists among the poor and even among children in rural areas that have access to these foods, which are creating an obesity pandemic.

For example, Tanzania, where I lived, has quite a few brands which are locally produced, and they’re extremely affordable now to people who would be considered lower middle class. We hear stories of people saving money to go buy those foods as well.

Also Read: How the Food You Eat Everyday is Slowly Killing You

Based on your research and experience working in East Africa and across the continent, how would you say culture influences our eating habits?”

Of course, there must be. I am not qualified to speak to it.

I think the fact that people are eating so much ugali is a reality. And so that’s why fortification, for example, of staple foods is really important. It’s because it’s going to be a long time, probably a decade, before we see a significant decrease in the consumption of staple foods like maize.

On the other hand, I talk to Kenyans who often say that they can’t wait to have the ability to go into a grocery store and buy packaged foods, processed foods. So, there’s an aspiration there.

Now, at ATNi, we do not demonise packaged foods. Rather, we say packaged foods are increasingly part of the market. We must make sure they’re regulated. We must make sure they are as healthy as they can be and tasty.

And that’s what we are engaged in, improving their overall healthiness because you cannot stop consumers from wanting convenience.

When we talk about packaged foods, are we referring solely to junk food, or does this also include traditionally-inspired foods that have been processed and packaged? Are there cases where traditional foods, once packaged, lose their nutritional value or even become unhealthy?

When I say packaged foods, I mean foods which would be on the formal market in formal packaging. They might be processed, they might not be processed. Mostly, they are processed.

According to data, on the packaged food global market, we’ve looked at about 60,000 products globally, and we’ve nutrient profiled each of them.

The data shows us that on average, using a health star rating system, that uses one to five rating system, five being the healthiest it can be in the diet, and one being the least healthy, 34% of global sales of packaged foods would be considered healthy.

So the rest are less healthy. And, we can argue about the nuance and the way the analysis was done, but it’s a very good indication that as people shift to more modern ways of consuming foods, they shift more and more to packaged foods, and those packaged foods tend to be dominated by processed foods.

And processed foods, in general, tend to be high in these additives like fats, sugars and salts. And taken together, that trend is unhealthy.

Now, that trend can be healthier, and that’s what we are doing as the modern food market grows in Kenya, let’s make sure there are healthier options available for Kenyans.

When it comes to local food production, several brands claim to be ‘Made in Kenya’ but are really just repackaging imported products. How can we influence these companies to truly invest in local production, especially of healthier foods? And have the multinationals move towards selling healthier foods as well?

Complementary foods that are often consumed by toddlers and young children during and mostly after breastfeeding, we’ve also done some analysis that shows that the least healthy of those come from the largest companies, often imported into Kenya.

What we are trying to do, and many of our partners are also involved in this, it’s not just ATNi, is to scale up local production.

But to do that, you will need impact investors, those, who say, okay, we realise this is not going to be the most profitable business, but we want our capital back after a period of time. We don’t necessarily want it back with a standard interest that you would expect from a bank, but we want it back with small interest and social or nutrition impact.

We want to see locally produced, healthier complementary foods. So there are quite a few initiatives now that we’re working on, UNICEF’s working on, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition are working on to do this very thing. And we are trying to identify small and medium enterprises, but also larger national enterprises that could produce more of these foods.

However, it will take significant concessional capital because you are working with multinationals who are producing these products at scale.

What does the future look like if we don’t handle this issue now, especially for East African countries?

If you look at what’s happened in the United States, where about 50% of calories are consumed through processed foods, you see that insurance is often paying for noncommunicable disease treatment.

One of the main non communicable disease is diabetes. The cost is huge. There’s also a loss of productivity.

I think if you looked at the United States or the United Kingdom, where the consumption of these foods is about 50%, that’s where Kenya might go. You would eventually go to a situation where people are eating less traditional diets and too many unhealthy foods.

They are not eating diverse diets. They are often eating highly processed foods, and they tend to be unhealthy in general. They’re not all unhealthy, but they’re generally unhealthy.

And then you would end up with a high burden for insurance. And then many people aren’t even going to have insurance, so they’re not going to be treated. Morbidity and mortality rates will go up significantly. And I’m afraid to say that it’s almost inevitable if policies aren’t put in place quickly.

Also Read: Ruto Under Pressure to Declare a National Emergency

Why does ATNi place particular focus on Kenya compared to other East African countries? What makes Kenya a priority in your work?

Because we can’t work everywhere. We can work where we are able to raise resources to do the work we do. And Kenya remains one of the focus countries of two of our major donors, the Gates Foundation. And the other one is the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, FCDO.

So we could have chosen a few other countries to go to among their priority list, but we decided on Kenya because of the need, feasibility for impact, political will and because many of us at ATNi have worked here before.

Given the complex dynamics of politics and accountability, especially when trying to hold institutions and organisations responsible, how is ATNi navigating these challenges in East Africa, while still managing to collaborate effectively with stakeholders on the ground?”

We are assessing dozens of companies, both in Kenya and Tanzania, these are food and beverage manufacturers, on how they’re delivering nutritious foods.

And, of course, to do that well, we like to also talk to those companies to really understand from the inside what they’re doing.

So we use a mix of interviews, data which is available in the public domain, as well as data and information that the companies give us. Using those information points, we try to understand how they are doing so that we can hold them to account.

Usually, in most countries, we are working with publicly listed companies.

These are companies that would be on a stock exchange, and they would have shareholders.

And when it’s available, we make the data also available to the shareholders, so that those of them who are responsible and want to invest in the long-term health of people, not just in financials, they can, as a shareholder, use our data.

For example, they can escalate to the boardroom of companies very important issues on marketing, very important issues on the healthiness of product portfolios. And it works because money talks and has power.

In Kenya, there are not a lot of food companies yet publicly listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange.

That is a barrier for us because one of our levers has sort of been removed. There are a few though, and we are mapping the investors of those few companies who are on the Nairobi Stock Exchange. So what does it leave us with? It leaves us with the most powerful one of all, which is policy.

And that’s why all of our assessment is being made available to the government, the Ministry of Health in Kenya, to KEBS, the Kenya Bureau of Standards, and of course, to our partners like APHRC, because they must have the tools, the data, the analysis, the recommendations available to really push possible food policies.

You mentioned that there’s been some progress in addressing nutritional deficiencies in Kenya, even though noncommunicable diseases continue to rise. How does it make you feel to witness this kind of improvement, knowing there’s still a long way to go?

Well, it shows you that with the right amount of effort and collaboration, things can get done. I am very proud of the work that I was able to support in Kenya for years on fortification.

And it started as voluntary, then it went to mandatory. But just because something’s mandatory doesn’t mean it actually works. Then it must be enforced. It has taken Kenya at least a decade, but they’ve done it.

Through good legislation, through good regulatory monitoring policies, through budgetary allocations, they have actually moved from no staple foods having fortificants added, to a fairly compliant system of fortified foods available to the general population.

If it can be done for fortification, it can be done for processed foods. We can move from voluntary measures to mandatory. We can mandate, in Kenya, labelling that shows what is healthy and what is not healthy. We can mandate fiscal policies that tax the bad food and subsidise the good food.

Kenya has made progress with fortification. They can certainly also regulate packaged food.

Do you think that’s possible?

I joined the support of the Kenya fortification program in 2011 and it has taken a decade to see that program’s success and get to a very well-regulated, modern food environment here in Kenya, where the packaged foods are healthier, clearly labelled, and taxed appropriately.

In the near future, what are some of the bold steps you would recommend Kenya take?

Here is the most exciting one for me. Kenya has the opportunity to get ahead of every single country on earth.

I would suggest that the Nairobi Stock Exchange moves to hold all food companies to account on the healthiness of their portfolios.

How? Disclose the information using standards. Put a nutrition indicator within the mandates of investment criteria so that when a company goes public on the stock exchange. Every year, when they submit their earnings report to investors, they also have to submit data on how healthy their foods are. That would be impactful.

Note that we are talking to the International Sustainability Standards Board, ISSB, about this. We have also been talking to the Securities and Exchange Board of India about the metric on nutrition. It is a challenging thing to do because it’s sector-specific.

I tend to go follow the money, and I think fiscal policies, as challenging as they are, could be scaled up and implemented better in most countries.

To get specific for Kenya, rather than just look at sugar-sweetened beverage tax, many of the foods which score particularly low on the new Kenya nutrient profile model? So if it’s unhealthy, then it would attract a tax to the company, not to the consumer.

If the Kenyan government could subsidise certain fresh fruits and vegetables so that those who cannot currently afford them could afford them in the future.

Quoting the World Bank, we say for every dollar invested in nutrition, they get 23 dollars in return, based on years and years of evidence. But it takes time and it takes investment. The government is the player who can make that investment.

Is your fight for better nutrition systems driven by personal conviction, or is it purely professional for you?

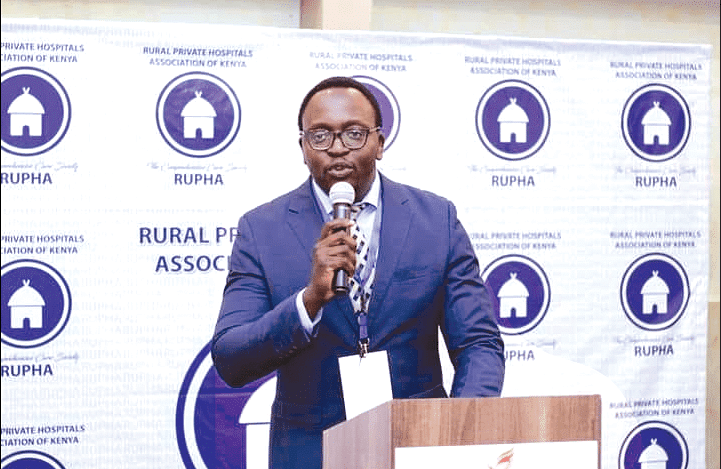

I got started in my career in the nineties, actually, on Mercy Ships. We were providing humanitarian aid as well as care from doctors and dentists to regions of the world. I was out in the South Pacific following devastating tropical storms.

I was just a deckhand. But ever since then, I had a passion to use my career to actually build something and help people at the same time, I thought that was a neat thing to do.

And of course, it’s personal in the sense that all of us eat. All of us want to be healthy. So improving nutrition is a very palatable, very practical thing to be involved in.

For our work, we don’t hand out food, and we often don’t see the beneficiary. I think that’s where visiting Kenya and hearing the issues from those who are on the ground, disseminating our data and our analysis, is really important because we hear things from them.

So its indirect, but these are positive stories. Of course, when I get the chance to go to a school meals program or visit a hospital where foods have been impacted by our work, it is exciting because you actually see the impact.

We try to understand how many people are being reached by our work. Having numbers like that, even if they’re based on some high-level assumptions, also helps us to ground truth the reality of what we are doing.

I am curious, how do you track the real-world impact of your work? You conduct research and release reports, but how do you ensure that the right people act on your findings?”

We have three things we’re doing. One is a very simple metric.

When we profile foods globally or in a country, we try to understand how many people access those foods. So the 60,000 products that I told you about, we’ve we estimate that around 900 million people globally access those. So almost a billion. That’s one very high-level metric.

Then, going down a level, about 34% of sales are derived from healthier food products out of those foods that are being accessed by 900 million. We need to see that go up to 50% by 2030.

Indicator number three is what we’re working on now. We’re trying to model the impact of the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and sweetened biscuits, and other sweet products like packaged cakes. What is the current negative impact of that?

And we are modelling what would be the extra productivity days of people if we’re successful in getting companies to reformulate and improve the healthiness of products? So, if they drop the sugar by a certain amount or if people stop consuming those products altogether, how much better will the people be? How many more productive days will they have per year? And then we can also help understand what the extra GDP would be for Kenya. So these are all numbers we are modelling now.

If healthy food’s are bad for business, how are you going to convince, industry, especially?

We will not.

If it is bad for business and there’s no laws preventing them, we’re not going to fully convince them. So that’s why we have to work with investors and policymakers. They can convince the industry because investors for example can decide not to invest in them any longer.

We have to work with, government so that policies are put in place. We also have some agreements with consumer organisations.

If consumer member organisations can take our data and give consumers the tools they need to know what to buy. That also helps drive demand. Let’s also acknowledge that there are some food industry players who want to do the right thing, and some are creating the business case themselves and doing good and working to leave the unhealthy food business completely.

Let’s move into products which can be healthier. So some companies are doing the right thing, and you’ll see that in our assessment. So we need to work with that group to see what the good practices are and then scale up those good practices.

And that all of those things together, I believe, build the business case.

How do you maintain a personal healthy lifestyle? Because you live in these times where millions of people are subconsciously consuming these unhealthy packaged foods every day?

If you want to know how much packaged food I eat, it’s very little, actually. I am fortunate that I can afford to buy fresh fruits and vegetables, and many cannot.

You know, that is one of the problems we have generally around the world, is that fresh fruits and vegetables often are more expensive than just buying the unhealthy packaged alternative, whatever that may be. Unhealthy carbs are very, very cheap, too cheap, in my opinion. I think they should be much more expensive.

And of course, exercise, like anybody else. I like tennis and try to work out in the gym every week.

Which is the one food that you would now consider unhealthy that you still enjoy?

I like donuts.

I grew up eating donuts, and I still, well, sometimes enjoy a donut. But it’s rare, but its rare. But it’s a nice splurge.

ATNi is not trying to do away with all these special treats. When we celebrated our ten-year anniversary two years ago, we probably had one of the least healthy cakes you’ve ever seen. It is okay to indulge from time to time. That’s why they’re called indulgences.

By the time you move on to something else from your role at ATNi, what is a legacy that you would like to leave behind? What will make you proud?

I would like to be able to say that ATNi was part of a movement to change the market so that healthier food options are more affordable. And we measure that through looking at the sales and revenue of companies, and are they deriving that from healthier food?

So if that has progressed due to our work, I’ll be very proud because that means globally we’ve affected a change that is sort of unstoppable, that is a market-based change, that is sustainable.

Two, I’d like to be part of making sure that environmental, social, governance investing has a nutrition indicator. It does not currently. Health is underreported on, and nutrition, not at all. So if by the time I leave, I can say that ATNi was directly involved in getting nutrition as part of the trillions of dollars os assets under management, looking at nutrition, that would be very, very exciting.

I think the third one would be if we could help countries like Kenya to have the tools, the research methodology, and knowledge to run these sorts of assessments themselves, I’d be very happy because it is more sustainable.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.