Two months ago, William Ruto was sworn-in as the fifth president of the republic of Kenya following one of the most closely contested presidential elections in Kenyan history.

Ruto won – his victory was unsuccessfully challenged at the apex court – by some 233, 211 votes. At least eight million registered voters boycotted the vote.

While those who voted for Ruto are optimistic that he will change particularly the economy, a significant number – close to seven million voters who voted for Raila Odinga – have expressed reservations on his ability to save the country’s economy for the simple reason that, they argue, he was part of the previous regime that messed the economy.

I asked a few Kenyans from different walks of life about their expectations with regard to the new regime’s economic policy in particular and overall performance in general.

Ruth Njeri, a trader at Toy market, who voted for the Kenya Kwanza Alliance believes Ruto will deliver his campaign pledges. “It is God who put him there. He will help him lead us well,” she said. When I asked her what she understands by the bottom-up economic model through which the Kenya Kwanza regime will endeavor to address Kenya’s economic challenges, she said she does not know what it means but she is certain it will work.

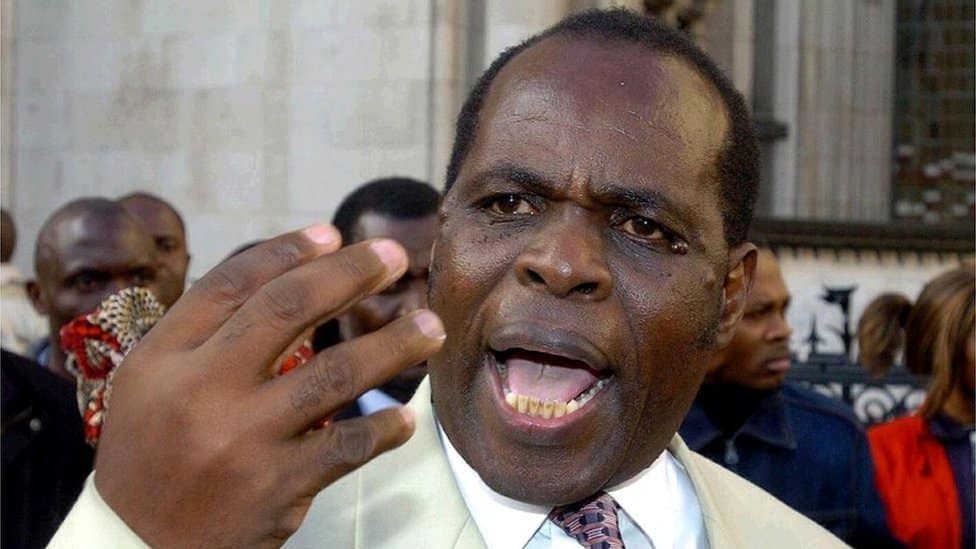

Dan Mwanzo, a die-hard Raila Odinga supporter and trader in the same market argues that Ruto is a political con who has perfected the art of deceit and doublespeak throughout his political career. “Huyo jamaa ni mkora sana, ile kitu ilimsaidia ni ati anajua kusema uongo (that guy – Ruto – is a con, what helped him is that he knows how to lie)

While propagating the idea of an innate optimism bias built into the human brain, Tali Sharot, associate professor of psychology at UCL, argues that “it is a peculiar empirical phenomenon that while people tend to be optimistic about their own future, they can at the same time be deeply pessimistic about the future of their nation or the world.”

In other words, Sharot argues that we normally tend to be optimistic rather than realistic when considering our individual future.

Jane Atieno who lives in Kibra says that even though she did not vote for him, she hopes Ruto will not renege on his promises. “Mimi naomba tu afaulu, Maisha imekua ngumu sana (I am praying that Ruto succeeds, life has become very difficult),” she said. The (single) mother of three lives on Ksh300 or less on a day and is worried about the rising cost of living.

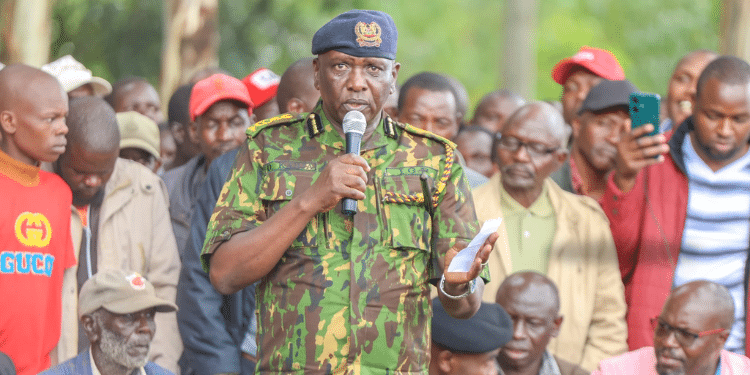

A senior police officer at Capitol Hill Police Station whom I talked to when I visited the station last week told me he does not think Ruto will do much to reform the police service. When I asked him whether we are going to see a decrease in cases in extrajudicial killings, he said, “that would require internal reforms within the service.” “For the high-profile murder cases, forget about it…these guys are wielder dealers, what they want fixed will be fixed,” he offered.

Pessimism

From the end of 1995 to the middle of 2015, European Union’s Eurobarometer surveys show, around 60 per cent of people anticipate that “their job situation will remain the same, while 20 per cent expect their situation to improve.”

If compared with the response of the same group of individuals considering the future of the economic situation in their home country, results show that “most people expect the economic situation in their home country to get worse or stay the same.”

If we feel more in control of our lives, Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests, we tend to be happier, healthier and more optimistic about the future. This could also help, as Our World in Data’s Max Roser points out, to explain the gap between individual and societal optimism: since we are in direct control of our own lives but not the destiny of the nation we feel more optimistic about ourselves.

A teacher at Kilimani Primary School who spoke to me on condition of anonymity believes the government has failed to address the plight of teachers sustainably. “The previous government weaponised different policies through the Teachers Service Commission to stifle our course. Teaching is still one of the most undervalued professions in this country,” she said.

At least 52 per cent of people globally believe that global poverty is rising. In reality, the opposite is true. In fact, Roser writes, “the share of people living in extreme poverty across the world has been declining for two centuries and in the last 20 years this positive development has been faster than ever before.”

But for Kennedy Moseti, a resident of Mukuru kwa Rueben, the argument that global poverty is declining does not make sense. He lives on Ksh200 daily, that is, if he is lucky. “Ni kama serikali ilitusahau (It is as if the government forgot about us), he told me.”

“In low-income or lower-middle-income countries, more people understand how global poverty has changed. People in richer countries on the other hand – in which the majority of the population escaped extreme poverty some generations ago – have a very wrong perception about what is happening to global poverty, writes Roser.

Surveys conducted by Our World in Data shows that “we do not only believe that the world is stagnating or declining, we also expect that this perceived stagnation or decline will continue into the future.” This pessimism about what is possible for the world, Roser emphasizes, matters politically.

Also Read: Of Power and Money: How Capitalism Facilitates Global Inequality

Nancy Maina, 43, a trader at Muthurwa market in downtown Nairobi, says she voted for Ruto because he came from a humble background and will not forget about the plight of the ordinary people.” Ukiangalia mahali ametoka…Ruto hawezi sahau mwanainchi wa chini (If you look at where he has come from…Ruto cannot forget about the ordinary person)

Roser argues thus: “Those who don’t expect that things get better in the first place will be less likely to demand actions that can bring positive developments about. The few optimists on the other hand will want to see the necessary changes for the improvements they are expecting.”

In addition, the survey suggests that there is a connection between our perception of the past and our hope for the future. “Those that were most pessimistic about the future tended to have the least basic knowledge on how the world has changed. Of those who could not give a single correct answer to the survey questions, only 17 per cent expect the world to be better off in the future. At the other end of the spectrum, those who had very good knowledge about how the world has changed were the most optimistic about the changes that we can achieve in the next 15 years,” the survey indicates.

An accurate understanding of how global health and poverty are improving, for instance, leaves no space for cynicism. As Roser puts it, those who are optimistic about the future can base their view on the knowledge that it is possible to change the world for the better, because they know that we did.

Patricia Waithera, a nurse at Pumwani Maternity Hospital notes that the facility has undergone tremendous reforms and if the available resources are managed efficiently, the largest maternal facility in Nairobi could become more reliable. “I expect to see more resources being channeled in healthcare. For instance, like in most health facilities, we need more beds in Pumwani,” she says.

Declinism

Declinism ideally refers to the belief that a country or some other institution is in decline. It was, as Roser notes, a prevalent feature of British political and economic history, whereby the decline of Britain as a world power was seen as the result of internal failures rather than international forces or global convergence. David Edgerton writes: “Declinism is beginning to appear as one of the last vestiges of imperial grandeur: for declinism holds, implicitly but clearly, that if Britain had done better, it would have remained a much larger player on the world stage.”

Dr Tom Odhiambo, a public intellectual and lecturer at the University of Nairobi, believes the political leadership nipped the Kenyan dream at the bud. “Kenya has failed to achieve its potential because of a greedy, incompetent and corrupt political leadership. Dr Joyce Nyairo, one of Kenya’s most important thinkers, told me in a virtual conversation recently that Kenyan political leadership, like their peers pretty much across the world, preach water and drink wine.

As Roser correctly recommends, there are three main reasons why we should try to combat social pessimism and declinism. The first reason, he says, is simple; indicators of living standards are significantly improving around the world. “By monitoring and researching these changes we can identify ways in which progress can be achieved. Over the long-run, say 50-100 years, human progress has been staggering with the benefits not confined to the richest or most powerful,” he writes.

He goes ahead to suggest that if our perceptions of the reality are wrong, we can end up prioritising the wrong things and making ineffectual change. Lastly, according to Roser, being optimistic can be good for your health, while having a pessimistic outlook can be detrimental to your health.