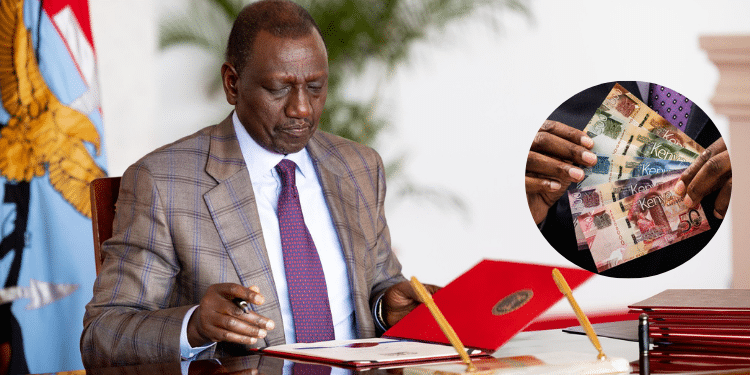

Recent years have seen heightened tension between taxpayers and the government over the level of taxation, with complaints that many tax measures are regressive and disproportionately burden low-income populations. Citizens, led by Gen Z’s, have voiced concerns over rising cost of living, especially as the government continues to impose taxes through Finance Acts on essential goods and services.

On the other hand, Kenya’s debt crisis places the government in a precarious situation. High levels of borrowing have limited the fiscal space available for critical public investments, forcing the state to explore alternative revenue sources. This environment has led to a contentious debate about balancing fiscal responsibility with economic growth

With the government facing the challenge of balancing debt repayment with the provision of essential services, addressing Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) must become a national priority. IFFs are defined as illegal movements of money or capital from one country to another, typically driven by practices such as tax evasion, trade mis invoicing, corruption, and money laundering.

These flows drain the economy of billions of dollars, severely limiting the resources available for essential public services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure development.

The battle against IFFs has gained traction as stakeholders explore innovative ways to curb revenue losses. The issue has escalated in significance as it directly impacts the country’s Domestic Resource Mobilization (DRM), stunting efforts to realize critical development goals, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

IFFs Posing Risks to Domestic Taxation

IFFs are often linked to global trade practices, making it a complex challenge that requires collaboration across borders. Kenya’s legislative framework, while improving, has not fully insulated the country from financial manipulation that drives IFFs. This necessitates new revenue-raising measures that confront the risk posed by IFFs while addressing domestic taxation concerns.

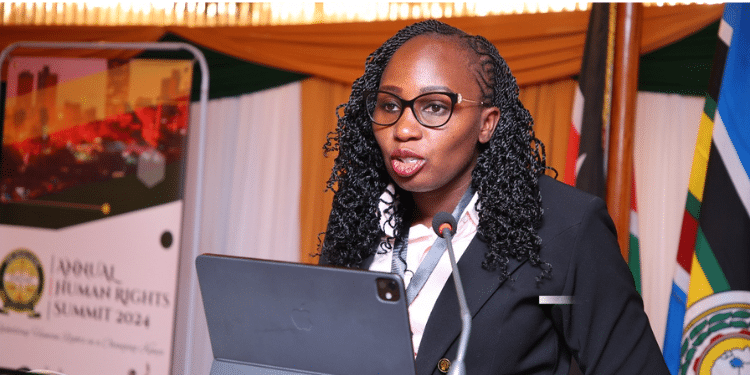

A recent review by the National Taxpayers Association (NTA) delves into the level of integration of IFF-related measures in Kenya’s revenue-raising initiatives. The review focused on Finance Bills and Finance Acts between the financial years 2022 to 2024. Despite the repeal of the Finance Act 2023 and the deletion of the Finance Bill 2024, the review explored the extent to which these legislative instruments aimed to align with international, regional, and national best practices to tackle IFFs.

According to the NTA’s findings, Kenya’s Finance Bills and Acts from 2022 to 2024 presented some progress towards addressing IFFs, although gaps remain. One significant step was the introduction of provisions for taxing digital assets, which opened new fronts for revenue collection. However, these efforts must be fortified by future legislation to fully align with IFF deterrence measures.

The review was based on desk research and interviews with experts in academia, legal practice, finance, revenue administration, and civil society organizations (CSOs). Although no taxpayers were interviewed, the perspectives gathered offer a glimpse into the ongoing challenges and opportunities for further integrating IFF-focused measures in Kenya’s fiscal policies.

Integrating Anti-IFF Measures in Future Finance Acts

To fully capitalize on the progress made, stakeholders must advocate for stronger integration of anti-IFF measures in future revenue bills and acts. The NTA recommends that the next cycle of revenue-raising measures include more robust provisions that align with international best practices, particularly in areas such as taxation of multinational corporations, digital economy regulations, and financial transparency.

The successful domestic adoption of these measures will require collaboration between government bodies, civil society, and the private sector. Furthermore, legislation should not only address existing gaps but also anticipate future trends in illicit financial activity, such as the rise of cryptocurrency and other digital financial systems.

The Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), led by its Digital Economy Tax Office, is taking critical steps to strengthen revenue collection while addressing financial misconduct.

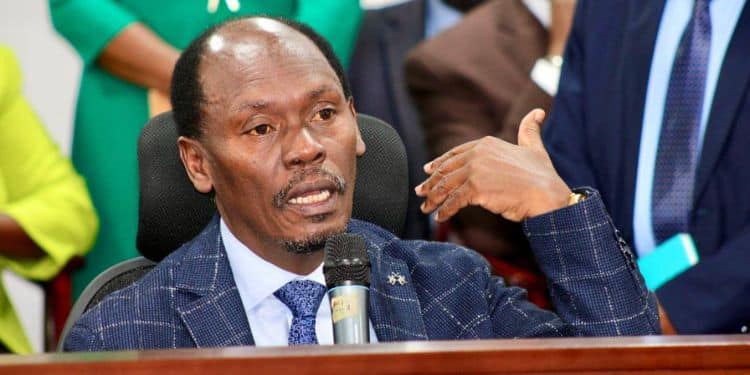

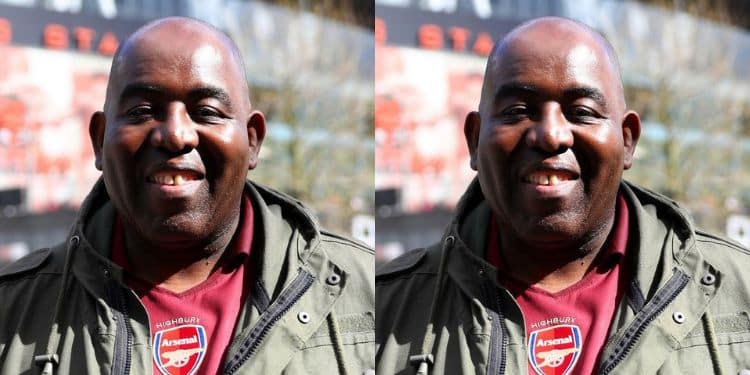

According to Nixon Omondi, the Digital Economy Tax Office Lead at KRA, the erosion of the national tax base due to IFFs has made it increasingly difficult to generate the revenue needed for effective budget planning.

He highlights the key initiatives introduced in the Finance Act 2023 and Finance Bill 2024, underscoring their significance in the fight against IFFs. Nixon Omondi explains that these legislative measures introduce key proposals aimed at combating IFFs while promoting a fairer and more transparent financial landscape.

Among the standout proposals in Finance Acts are:

Enhanced Reporting: Stricter financial reporting and disclosure requirements have been introduced to ensure transparency and reduce the chances of profit shifting—a practice often employed by multinational corporations to minimize their tax liabilities by shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

Increased Penalties: The new legislation imposes higher fines and penalties for non-compliance and fraudulent activities, acting as a deterrent for entities seeking to engage in illicit financial practices.

Anti-Money Laundering (AML): Kenya has strengthened its customer due diligence regulations to prevent abuse of financial incentives and ensure compliance with AML frameworks. This includes tightening controls on financial institutions and improving their capacity to detect suspicious transactions.

Tax Information Exchange: To foster global cooperation, Kenya has expanded its tax information exchange agreements with other countries. This “country-to-country” approach allows the sharing of tax-related data, making it harder for individuals and businesses to hide assets and income across borders.

Taxation on Digital Markets: In recognition of the growing digital economy, Kenya has also focused on better monitoring and taxing e-commerce and digital transactions. With digital platforms becoming a significant source of revenue, this initiative is expected to increase transparency and prevent tax evasion in the digital space.

Domestic Revenue Mobilization

While tackling IFFs, the new legislative measures also focus on bolstering Domestic Revenue Mobilization (DRM). For Kenya, IFFs not only hamper tax collection but also exacerbate fiscal deficits, hindering the country’s ability to fund crucial sectors such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure development.

In an effort to address tax avoidance by multinational corporations, the Finance Bill 2024 introduced two critical tax measures that are directly linked to DRM:

One, Minimum Top-Up Tax ensures that multinational corporations operating in Kenya pay a minimum tax rate of 15%, even if they shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions. By setting a minimum tax threshold, the government seeks to prevent multinationals from exploiting loopholes in international tax systems to avoid paying their fair share of taxes.

In Kenya’s quest for economic development, Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Economic Processing Zones (EPZs) have long been hailed as key drivers of growth, attracting multinational corporations (MNCs) and spurring industrialization. However, these zones, designed to foster economic activity through preferential tax treatments, are increasingly seen as a double-edged sword.

As Catherine Ngina Mutava, Associate Director of the Strathmore Tax Research Centre, highlights, the preferential tax breaks offered within these zones contribute to the global phenomenon of Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs), raising questions about their true economic benefits.

Also Read: Why Africa Needs to Combat Illicit Money Flow

Role of Special Economic Zones and Economic Processing Zones

Special Economic Zones and Economic Processing Zones are established in many countries to stimulate investment, promote exports, and create employment. These zones often offer tax breaks, lower tariffs, and exemptions from certain regulations as incentives to attract foreign and domestic businesses. Globally, SEZs and EPZs have proven effective in catalyzing economic activity, but they have also facilitated IFFs, including profit shifting and tax avoidance.

In Kenya, the preferential tax treatment granted to businesses in these zones is classified as “tax expenditures.” While Kenya’s government views these tax breaks as crucial for driving economic growth, experts like Mutava argue that the exclusion of SEZs and EPZs from the country’s tax expenditure report reflects a significant gap in addressing IFFs.

These tax breaks, though intended to boost economic activity, also create opportunities for companies to shift profits to lower-tax jurisdictions, ultimately reducing domestic revenue.

And two, Significant Presence designed to target companies with substantial economic activities in Kenya but no physical presence. Significant Presence tax ensures that companies profiting from the Kenyan market contribute to the country’s tax base.

This measure addresses the challenges posed by digital companies that operate across borders without being physically present in the countries where they generate profits.

These measures, while primarily aimed at expanding the tax base, also indirectly combat IFFs by preventing profit shifting and tax avoidance. However, Nixon Omondi notes that the primary focus remains on ensuring that Kenya broadens its tax base and mobilizes domestic resources more effectively.

The proposals in the Finance Act 2023 and Finance Bill 2024 reflect the Kenyan government’s growing emphasis on broadening the tax base while easing the burden on individual taxpayers and sectors that are already heavily taxed. Kenya’s citizens and corporates have raised concerns over the high tax levels, particularly regarding taxes on essential goods and services that disproportionately affect lower-income groups.

Exploring Alternative Revenue Sources

The government’s new approach seeks to explore alternative revenue sources, such as the digital economy, without further straining vulnerable sectors.

According to Dennis Moroga, a lecturer at Moi University and Partner at Moroga Wangwi Advocates, recent legislative efforts—including the Finance Act 2022 and Finance Act 2023—have introduced important changes aimed at enhancing transparency and closing financial loopholes. However, these measures have also encountered significant challenges.

The Finance Act 2023, through Section 6A, introduced pivotal reforms to improve transparency and curtail the misuse of corporate structures for illicit purposes. One of the most significant provisions of this act is the Beneficial Ownership Disclosure, which mandates that companies disclose their beneficial owners—the individuals who ultimately control or own these companies. This provision is designed to prevent individuals from hiding behind anonymous corporate entities to engage in illicit activities like money laundering or tax evasion.

In addition to beneficial ownership disclosure, the Finance Act 2023 strengthened financial reporting requirements for entities involved in financial transactions. These tighter regulations aim to ensure that suspicious activities are flagged and reported to the appropriate authorities, making it harder for illicit actors to exploit Kenya’s financial system.

However, despite these legislative strides, challenges remain. The implementation of these provisions faces practical hurdles, such as the potential conflicts between new reporting requirements and the principle of lawyer-client confidentiality.

This is particularly relevant because, in Kenya, advocates are now considered reporting agents under these laws. Advocates are required to report suspicious financial activities they encounter during their professional duties, raising concerns about the burden this place on them, as well as the risk of undermining their confidentiality obligations to their clients.

The success of these reporting measures will depend on how well Kenya manages to balance the need for transparency with respect for legal confidentiality.

The Beneficial Ownership Disclosure is a significant hit, as it aligns Kenya with international best practices in transparency and corporate governance. By making it more difficult for illicit actors to hide behind complex corporate structures, this provision has the potential to curtail a significant portion of IFFs.

Monitoring of Financial Transactions

The Enhanced Reporting Requirements also reflect a move in the right direction. By compelling entities to report suspicious financial activities, Kenya is creating a more robust framework for identifying and addressing IFFs. These measures are designed to improve the monitoring of financial transactions and increase the accountability of corporate entities.

However, there are misses as well. The effectiveness of these measures depends heavily on their implementation. The practical challenges posed by the inclusion of advocates as reporting agents cannot be overlooked. For many lawyers, the conflict between their duty to report suspicious activities and their obligation to maintain client confidentiality creates a moral and legal dilemma.

Additionally, the administrative burden placed on advocates may hinder the smooth implementation of these reporting requirements, potentially reducing their effectiveness.

Beyond the technical aspects of combating IFFs, Kenya has also faced significant public opposition to some of the tax changes introduced in the Finance Acts. According to Moroga, this backlash stems from several interconnected factors.

First, the method of implementing tax changes plays a crucial role in generating public opposition. Finance Bills often introduce new taxes abruptly, without adequate public consultation. When tax policies are seen as being imposed without sufficient stakeholder engagement, they are likely to face resistance. This is particularly true in cases where the public perceives that the tax changes are being rushed through the legislative process.

Second, a lack of public understanding about emerging business models and their corresponding tax implications exacerbates opposition. For instance, the taxation of digital markets and other new economic activities may be met with confusion and resistance from taxpayers who do not fully understand how these industries are taxed.

This knowledge gap often leads to accusations of unfairness, particularly when the new taxes appear to disproportionately affect certain sectors or income groups.

Political Considerations and Lobbying

Finally, political considerations and lobbying efforts by affected industries also play a significant role in shaping the public’s response to new tax measures. Governments may find themselves pressured to withdraw or modify tax policies to appease powerful interest groups or to maintain political support.

This creates a perception that tax changes are driven by political expediency rather than the public interest, further fueling discontent.

In the broader context, Kenya’s fiscal policy must also address the root causes of public opposition to tax changes. Greater public engagement, clearer communication, and more deliberate policymaking are essential to ensure that tax reforms are not only effective but also equitable and broadly accepted.

Combating IFFs requires a comprehensive approach, and Kenya’s continued progress will depend on its ability to integrate these measures into a cohesive strategy that benefits all stakeholders.

The Medium-Term Revenue Strategy (MTRS) provides a blueprint for how Kenya intends to address the tax expenditure dilemma while also reducing opportunities for IFFs.

The MTRS outlines a plan to reduce VAT tax expenditures—particularly on essential goods—over the next three years, with the aim of keeping these goods affordable for consumers. By prioritizing tax expenditures in sectors that directly impact the lives of ordinary Kenyans, the strategy seeks to protect vulnerable populations from the regressive effects of consumption taxes.

SEZs and EPZs

However, the challenge lies in striking a balance between protecting the poor and reducing the preferential treatment offered to MNCs and corporations in SEZs and EPZs. While tax incentives may attract investment, they also diminish the government’s capacity to mobilize domestic resources. Mutava warns that Kenya’s current approach, which excludes SEZs and EPZs from scrutiny as potential sources of IFFs, risks undermining the broader goal of improving Domestic Revenue Mobilization .

The Medium Term Revenue Strategy represents a step in the right direction by seeking to reduce VAT tax expenditures on essential goods while also addressing tax avoidance among larger entities. However, Mutava’s insights highlight the need for a more comprehensive approach that includes SEZs and EPZs in Kenya’s tax expenditure report, ensuring that these zones do not become havens for profit shifting and other forms of tax avoidance.

Ultimately, Kenya’s path forward will require a delicate balancing act—one that protects the vulnerable, fosters economic growth, and closes the loopholes that allow IFFs to thrive. By revisiting its approach to tax expenditures in SEZs and EPZs, Kenya can take a significant step toward reducing the loss of domestic revenue and achieving more sustainable economic growth.

One of the most notable proposals in the Finance Bill 2024 is the removal of the income exemption for registered family trusts. Traditionally, trusts, including family trusts, have been used by wealthy individuals as a means to shield income or assets from taxation. By registering their assets under trusts, particularly in jurisdictions with favorable tax laws, individuals could avoid paying taxes on these assets, thus reducing their contribution to the tax base.

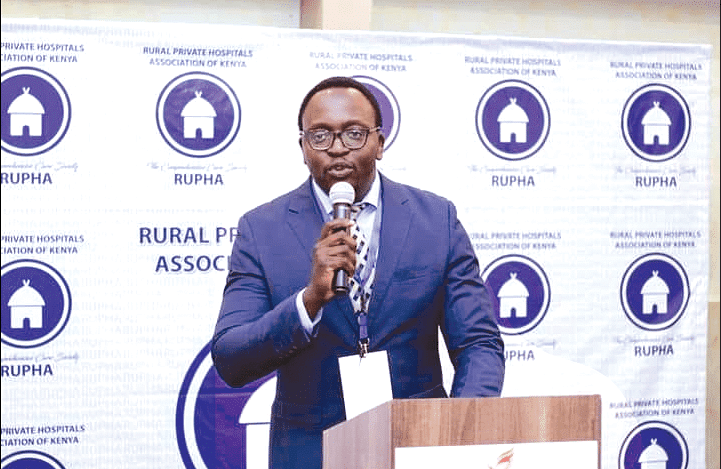

Robert Maina, a member of the Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Kenya (ICPAK), notes that this proposal seeks to strengthen anti-money laundering (AML) measures and ensure that wealthier individuals contribute fairly to the national tax base. The government’s move to delete this exemption is a step towards closing loopholes that have allowed tax avoidance and evasion. It also aligns with global efforts to increase financial transparency and prevent the misuse of trusts for money laundering and other illicit activities.

Maina explains that this measure promotes greater tax equity by removing the special privileges that trusts have enjoyed in the past. With these exemptions gone, trusts will be taxed just like any other

income-generating entity, ensuring that the wealthy pay their fair share and bolstering revenue collection for pro-poor policies and social programs.

Withholding Tax

Another significant proposal in the Finance Bill 2024 is the introduction of a 5% withholding tax (WHIT) on new bonds. This measure targets interest income, including that earned by non-residents, as a way of enhancing DRM. While this new tax may reduce the attractiveness of Kenyan bonds for some investors—particularly those engaged in arbitrage or using bonds to “clean” money—it represents an important step in ensuring that interest income is taxed.

Maina highlights that withholding taxes on bonds are a common practice in many jurisdictions, and this move by the Kenyan government is a natural progression in its broader efforts to discourage tax avoidance. By taxing the interest income generated by bonds, the government can better capture a share of the returns earned by investors, thereby increasing revenue for social spending and economic development.

However, the introduction of this tax may create some short-term challenges in the bond market. Investors, especially non-residents, could be less inclined to purchase Kenyan bonds if they perceive the tax as diminishing their returns. Nonetheless, the long-term goal of enhancing DRM through better tax compliance and collection remains crucial for the country’s fiscal health.

In its fight against IFFs, the government also aims to curb tax avoidance in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) by introducing a Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on property transfers within these zones. SEZs have been traditionally used as tools to attract investment through favorable tax regimes, but they have also become hotspots for profit shifting and other illicit financial activities.

Also Read: Tax the Rich to Beat Poverty: Kenya’s Extreme Inequality Out of Control

Why Impose Capital Gains Tax

By imposing a CGT on property transactions in SEZs, the government hopes to capture revenue from these high-value transactions and reduce the opportunities for tax avoidance. Maina emphasizes that while this measure is a step in the right direction, its effectiveness will depend on the consistent enforcement of tax policies across all agreements and jurisdictions.

Kenya has faced challenges in the past when it comes to the transparency and consistency of its tax agreements with foreign investors. Loopholes created by these agreements can undermine efforts to tax property transfers and other transactions effectively. Maina cautions that unless these agreements are scrutinized and harmonized with national tax laws, the introduction of CGT in SEZs may have limited success in addressing IFFs.

As part of its broader strategy to combat IFFs, Kenya is also prioritizing international collaboration and information sharing. By working with other countries to exchange tax information, the government aims to reduce the opportunities for Kenyan assets to be hidden abroad and avoid taxation.

Kenya’s participation in global initiatives like the OECD’s Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) further reinforces these efforts.

Addressing IFFs could serve as an alternative path to revenue generation, reducing the need to overtax already-burdened citizens. By diversifying the tax base and focusing on untapped sources like digital

assets, the government could alleviate pressure on essential goods and services. This, in turn, would promote economic inclusivity and drive Kenya closer to achieving its development goals.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel for real-time news updates.

https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaB3k54HltYFiQ1f2i2C