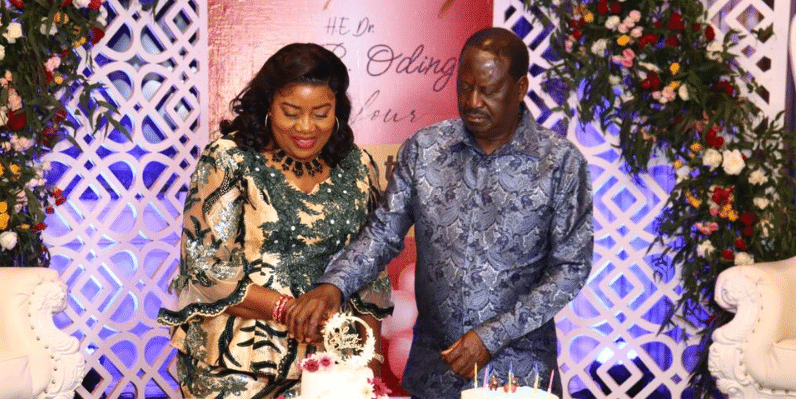

I was not shocked by the Supreme Court’s rejection of Raila Odinga’s petition against the IEBC declaring Deputy President William Ruto the President-elect. The previous elections in 2007, 2013 and 2017 had also been deeply flawed and fraud-filled but the IEBC’s declared candidate was nevertheless ushered into the presidential office each time.

So, I awaited the IEBC’s declaration with only muted hope, so this decision was not a huge surprise. But horrified I definitely was.

If anything, there was an even stronger case of electoral wrongdoing in the just concluded election. Indeed, the Court said it had found considerable evidence of “dysfunction” and “malaise” and the “obvious need for far-reaching reforms” in the IEBC.

But the Court still held that the IEBC lawfully declared Mr. Ruto President-elect!

Possible Charges

Interestingly, during the course of the fascinating hearing, the Court seemed to be headed towards a considered and tempered judgement, whatever that might be.

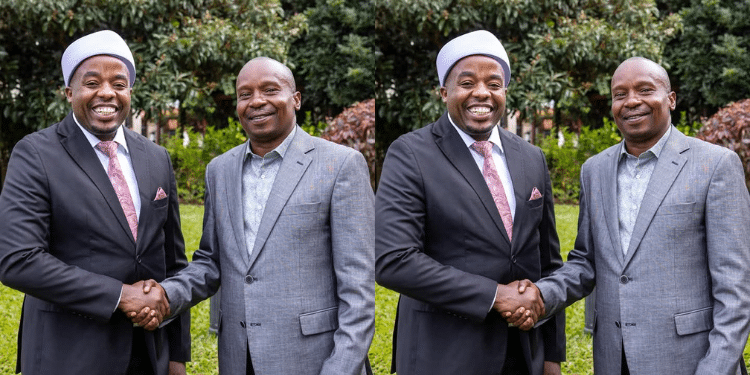

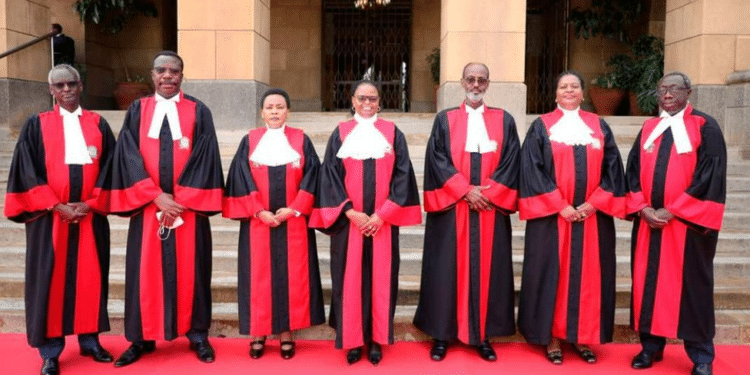

Justice Koome had skillfully handled the proceedings, and she and the other Justices had asked probing questions about multiple IEBC failures and the petitioners’ submissions.

But the judges’ thinking changed dramatically during their weekend deliberations, and on Monday a spellbound nation witnessed a unanimous court categorically rejecting, in the most aggressive way, every single complaint by the multiple petitioners.

The Justices debunked and even mocked some of the submissions, going as far as warning about possible charges of criminality being filed against them!

As The Kenya Times and other news outlets reported, “the top court used strong language in dismissing the case. The judgment discredited the evidence presented by the petitioners as ‘hot air, outright forgeries, red herring, wild goose chase and unproven hypotheses’… All the 23 grounds listed in the 72-page petition filed by Mr. Odinga and his running mate Martha Karua in the petition fell flat.”

Justices on the Supreme Court are some of Kenya’s most auspicious, learned, and independent legal minds.

It strains the imagination that on the extremely complex 63 legal decisions that had to be made, (seven justices, nine counts), not even one thought that the election was compromised.

Unrealistic Judgment

Supreme Courts throughout the world have numerous judges because their decisions have a profound impact on their societies’ futures. A larger bench ensures that no vital dimensions of the case are overlooked.

So, two or three or even four justices cannot be trusted with that decision. In addition, diverse opinions or dissent add to the Court’s legitimacy and credibility.

Unanimous verdicts are associated not with justice, but with juries since criminal trials often need unanimity for conviction. But unanimity is not the goal of a Supreme Court case.

So, except in totalitarian or dictatorial societies, unanimity in Supreme Courts is extremely rare, as Justices wish to leave a legacy of their learnedness and their independence on the invariably grave issues they are ruling on.

Decisions on a presidential election, which determines a nation’s destiny for 5 and often 10 years, are easily the most momentous the Court makes.

How then did this decision of the seven justices turn out to be identical on so many multiple counts? Did the Chief Justice or one of the others persuade the judges that a unanimous outcome was essential so that that Kenyans would be less likely to question their verdict? I definitely don’t think so – the opposite would be true, I would presume.

Or did the justices decide that there was safety in numbers and the verdict would be irreproachable. Again, I don’t think so – a split verdict, even a 6 to 1, would be more persuasive and credible.

Kenyans are eagerly looking forward to the final judgement to learn the reasoning that underlay this unanimity. But in the meantime, we do have a judgement that is final and irreversible, so lawyers and commentators have an obligation to discuss and critique it for the very expectant audiences.

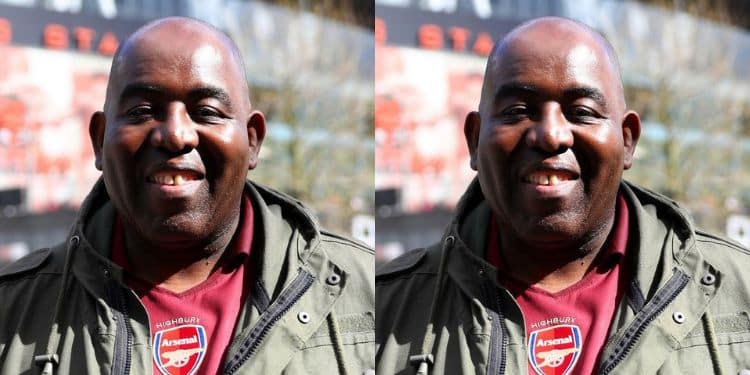

Senior Counsel James Orengo’s comments right after the judgment captured it all. He “vehemently disagreed” with the Court’s decision. “It is unrealistic,” he said “that we lost on ALL the grounds. The Court was looking for things to destroy our case with, but not taking sufficient time to look at what happened on the other side.”

As mentioned earlier, it was also disturbing for many that there were warnings, made at considerable length, that the Court directed at the petitioners and their highly learned counsels.

To quote just a few small snippets:

“We must remind counsel who appear before this Court…of the provisions of Sections 113 and 114 of Penal Code, that swearing to falsehoods is a criminal offence, as is presenting misleading or fabricated evidence…Any person who swears falsely or makes a false affirmation…would have amounted to perjury.”

Every element in the above quote is well-known, so why was it spelled out at such length, and why seemingly directed at the petitioners’ corner only? For example, IEBC chairman Wafula Chebukati “published a Gazette Notice in which he designated himself as the Presidential Returning Officer, a position unknown in law and the Constitution,” Justice Koome quoted. Did that not qualify for serious rebuke? And who will be charged with the clearly illicit role Jose Camargo, of Venezuela, played with his access to the server?

Then there was the declaration of the election outcome when so many results had still not been verified. Where did the push come from to deliver a verdict prematurely, when IEBC still had another 24 hours to make its final determination.

But what troubled me most was Mr Chebukati announcing the result when four of the seven commissioners had already indicated their dissent.

The Chief Justice herself had asked Mr Chebukati why he did not mention in his declaration that there had been serious dissent within the commissioners.

Indeed, is a majority not legally required for the all-crucial declaration?

Does a minority decision that was read out by Mr Chebukati not hugely undermine its credibility, especially as it was read prematurely”? And no less important, he spoke right after four of the seven commissioners had minutes earlier spelled out their objections at a press conference just before he spoke?

Does the Court’s decision that a majority is not needed for the IEBC verdict mean that the Chairman’s solo judgement, over the objections of all the other six justices, would also be lawful in the future? And even if the four dissenting commissioners did not speak up earlier, doesn’t their refusal to participate in the final judgment nevertheless render it unlawful?

I am not a lawyer, but my questions are based on logic and common sense – questions very much on the mind of very many Kenyans; Ultimately the Court’s standing and authority depend on whether Kenyans as a whole agree with and support the Court.

Rebuking Petitioners

The harsh rebukes and veiled warnings to petitioners and counsels startled me!

This will surely make future petitions against IEBC’s presidential declarations a fraught affair. Indeed, it is possible that many of the current Justices will again be assessing petitions against the IEBC’s presidential declaration in 2027 (if there are any after these warnings).

Five years hence, President Ruto will likely be a candidate as the incumbent president, when his informal authority over the IEBC and the Court will add additional (unconstitutional) power to influence the outcome.

It was very interesting for me that despite upholding the IEBC verdict, the judges pointed to profound IEBC weaknesses in conducting the election. Let me cite a few examples:

“Clearly, the current dysfunctionality at the commission impugns the state of its corporate governance. All this in our view, points to a serious malaise in the governance of an institution entrusted with one of the monumental tasks of midwifing our democracy. An institution that obviously needs far-reaching reforms. The Chairperson on his part, did not make matters any better by maintaining a stoic silence even as things appeared to be falling apart”.

The postponement of the elections in major Azimio strongholds such as Mombasa and Kakamega “was occasioned by a genuine mistake which could have been avoided had IEBC had been more diligent” – but it did not diminish turnout on August 9, they contended.

These are damning findings, but not a single justice was persuaded that this combination of failures must have affected the IEBC verdict. Can a dysfunctional IEBC suffering from such serious weaknesses conduct a credible election? I do not think so.

But by deciding that it was only the petitioners who had to prove their case, the Court let IEBC off the hook.

This definitely is not acceptable.

The IEBC was budgeted an astronomical $385 million to conduct an election which would reflect the voters desire and shape our nation’s foreseeable destiny. What we saw play out in an election in which the declared winner exceeded the 50 per cent goal by a tiny margin leaves a lousy taste.

Server Access

Senior Counsel Philip Murgor, representing Mr. Odinga, pointed out that the servers contained all the secrets about what the election results were. “But the Supreme Court registrar’s report was completely silent on the failure to open the IEBC servers. And the documented involvement of the Venezuelans for half a month before the elections was set aside.”

Since servers lie at the heart of the election outcome, how can the petitioners ever hope to win a petition if they cannot receive full access?

Compromised Supreme Court

In 2017, we had got the first example of our Supreme Court’s potential when it stunned the world by making Kenya the first-ever country in Africa to nullify the election of a president.”

Given all the IEBC’s documented failures, the current Court has reversed that gain.

Supreme Court petitions are a crucial determinant of post-election peace. It is a time of highly charged emotions and passionate commitment to their chosen leaders, and tens of thousands have worked on the campaign and are exhausted and vulnerable at the end. The petitions in a Supreme Court diminish these tensions by providing breathing room and hope for redress for the losing candidate and his passionate supporters.

But if the petitions fail time after time, their raison d’etre will collapse, along with faith in democracy.

This is the fourth straight presidential outcome that has been bitterly disputed. It has led to a lot of dismay and cynicism among Kenyans. Hence the dramatic fall in turnout of voters, from a high of nearly 85 percent to only 65 percent this time round.

We must break this vicious cycle to keep Kenya peaceful. As my good friend Rev Gabriel Odima powerfully wrote in the IPS news service, “When electoral fraud began to replace the ballot as means to install rulers like in the case of Kenya today, corruption, suppression of human rights and freedoms became the leading force of governance in Africa.”

I am afraid that those determined to win elections at all costs care not a hoot for such consequences.

They want the political and economic power that a presidency confers and are prepared to risk even the country going up in flames as it happened back in 2007.