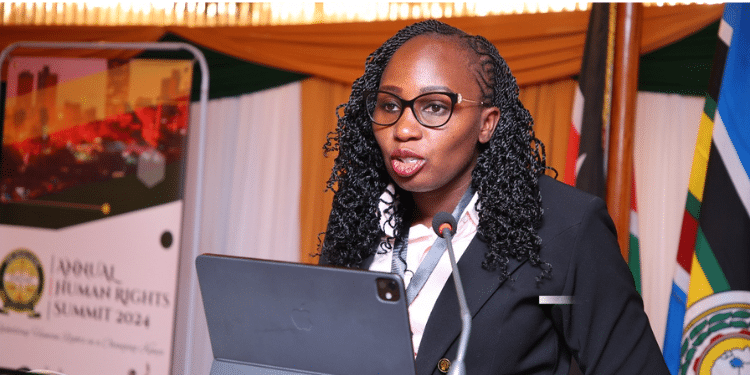

On February 18, 2025, an online stakeholder consultation took place as part of the ongoing intergovernmental process at the United Nations (UN) to establish a multidisciplinary Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and advance the Global Dialogue on AI Governance. The meeting convened approximately 500 participants, including representatives from NGOs, the private sector, and civil society, to discuss the risks, opportunities, expectations, and challenges of these two initiatives.

However, as discussions unfolded, it became glaringly apparent that voices from the Global South were either absent or unheard. While intergovernmental processes are structured to prioritize government representatives, this approach is wholly inadequate when it comes to AI governance. Artificial intelligence is not a technology that exists in isolation, nor should it be governed within the confines of political negotiations that serve short-term interests. AI is already reshaping economies, disrupting labor markets, influencing social structures, and redefining global power dynamics—making its governance one of the most critical ethical and geopolitical issues of our time.

Yet rather than ensuring a truly multilateral, inclusive, and participatory process, the discussions seemed to reflect the same North-South divide that has historically hindered progress in climate action, economic development, and digital equity. The result? An AI governance framework that risks being dictated by a handful of powerful nations and corporate interests, leaving behind those who are most vulnerable to the technology’s unintended consequences.

The Missing Voices: Indigenous and Vulnerable Communities

As someone who firmly believes in AI’s potential to address societal challenges and drive sustainable development, I found the lack of representation from indigenous and vulnerable communities deeply troubling. These communities—often excluded from major policy discussions—are the ones who bear the brunt of environmental degradation, economic inequality, and the digital divide.

Also Read: Ai is the Future: Exploring the Exciting Possibilities of Artificial Intelligence

While Silicon Valley debates the ethical risks of AI-powered automation, small-scale farmers in rural Africa, Latin America, and Asia face the existential threat of agriculture being disrupted by AI-driven agribusiness monopolies. While AI labs in major tech hubs discuss large language models (LLMs), millions of indigenous people lack access to digital infrastructure, let alone AI-powered tools that could amplify their voices and protect their cultural heritage. While wealthy nations focus on AI’s potential for economic growth, small island developing states (SIDS) and coastal communities are struggling to harness AI for climate adaptation, ocean conservation, and food security.

Without these perspectives, AI governance risks becoming not only incomplete but also profoundly inequitable, reinforcing the very structural disparities that AI has the potential to address.

Technology for Whom? Rethinking AI Priorities

During my work in the field, I have frequently encountered indigenous communities whose languages are not widely recognized or documented. I often wished for technological tools that could bridge this

communication gap, allowing me to listen to their concerns in their native languages and understand their priorities without intermediaries. However, this led me to confront a deeper reality:

- The same AI-driven language models that could enable communication could also be designed to document and preserve endangered languages, ensuring that indigenous knowledge systems are not erased in the digital era.

- The same AI-driven data analysis that is being used to maximize corporate profits could instead be harnessed for community-led conservation, real-time climate monitoring, and biodiversity protection.

- The same AI investments that fuel autonomous financial trading systems could be redirected toward precision agriculture, food security solutions, and climate resilience for smallholder farmers.

This raises a critical question: How do we ensure that AI development prioritizes the needs of marginalized communities rather than catering solely to market-driven, short-term projects?

The Funding Dilemma: Short-Term Profits vs. Long-Term Impact

Beyond the technical and ethical challenges, there is also a funding dilemma:

- How do we shift investment priorities from short-term, rapid-return projects toward AI-driven solutions that genuinely serve marginalized communities?

- Why do UN-directed funds, social impact investments, and development bank financing continue to prioritize short-term, high-visibility AI projects rather than long-term, community-driven initiatives?

- Why is AI research overwhelmingly concentrated in a handful of elite institutions in the Global North, while research in and for the Global South remains underfunded and underdeveloped?

Also Read: Embracing AI in Schools and Colleges While Safeguarding Human Agency

If AI governance is to be truly inclusive, the financial mechanisms that shape its development must also be restructured. We need to rethink how funding is allocated, ensuring that AI is developed not only for marginalized communities but with them, through collaborative, interdisciplinary, and culturally informed approaches.

The Role of the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI

This is precisely where the Multidisciplinary Independent International Scientific Panel on AI—currently under discussion at the UN—gains critical importance. If this panel is to be anything more than another bureaucratic exercise, it must include voices from indigenous and vulnerable communities.

- It should not just consult these communities but actively integrate them into decision-making processes.

- It should not merely assess AI risks and opportunities from a technical perspective but prioritize ethical, social, and environmental considerations.

- It must challenge the notion that AI governance should be dictated by those who have the most resources, rather than those who have the most at stake.

A Call for Global AI Equity

If AI governance is to be ethical, inclusive, and globally beneficial, it must acknowledge that:

- The solutions designed in the high-tech labs of the Global North should not dictate the realities of those living in the Global South.

- AI governance must go beyond intergovernmental negotiations and include multi-stakeholder participation—from local communities to grassroots organizations.

- AI must be seen not just as a tool of economic growth, but as a force for social justice, environmental protection, and human dignity.

The current trajectory of AI governance risks deepening global inequalities rather than bridging them. We have a responsibility—both as policymakers and as members of civil society—to ensure that AI does not replicate the same colonial patterns of exclusion and marginalization that have shaped technological development for centuries.

Only by embracing a truly collaborative, multidisciplinary, and people-centered approach can AI fulfill its true promise—not as a tool of exclusion, but as a force for empowerment and equity.

This article was written by Amaj Rahimi-Midani, a Costa Rican-Iranian environmental scientist and founder of Poseidon-AI. He collaborates with international organizations to implement sustainable practices in water, soil, aquaculture, and fisheries worldwide.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and join our WhatsApp Group for real-time news updates.