What would you do if your daughter had to skip school every month because you couldn’t afford pads? For many families in Isiolo, this is not a hypothetical question; it is the silent struggle of countless girls in Northern Kenya, and Amina Guyo is determined to change it.

When Amina Guyo was growing up in Isiolo, periods were something you never spoke about. Not with your parents, not with your teachers, and definitely not with the boys in class.

However, years later, she is on a mission to change that silence into action. Amina is showing up with something different.

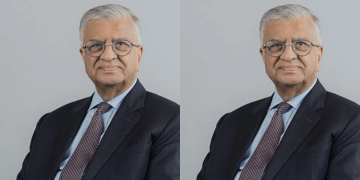

Skills, conversations, and a lot of compassion. Through her organisation SITIRI, she is teaching young girls about menstrual health and hygiene, and reminding them that their periods shouldn’t come with shame.

Additionally, Amina is a Youth Advisor at UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund), where she advises and guides on youth-related matters regarding SRHR (sexual and Reproductive Health Rights).

Amina, what does period poverty look like in your community? Can you paint us a picture of what many girls and women are going through?

Period poverty is often misunderstood. Many assume it only refers to the lack of access to menstrual products. However, it goes far beyond that.

Period poverty includes the absence of accurate information about menstruation, limited or no access to safe and hygienic menstrual products, and a lack of appropriate facilities to change and dispose of those products with dignity.

I come from Isiolo in Northern Kenya, and in the town areas, many of the basic needs for menstrual hygiene are available. There are multiple shops that stock sanitary products, access to clean water is relatively reliable, and there are toilets where girls and women can safely change and dispose of used sanitary products.

However, in the rural parts of Isiolo, there are very few, if any, shops where menstrual products can be purchased. Many girls resort to using old pieces of cloth in place of sanitary pads, which can be uncomfortable, unhygienic, and unsafe.

Access to water is also a major challenge. Some families must travel long distances to fetch even small amounts of water, making it difficult for girls to maintain proper menstrual hygiene. The infrastructure in these areas is severely lacking. On average, there is only one toilet shared between five households, making it extremely difficult for girls and women to find a private, clean space to change or dispose of their menstrual products.

As a result, many suffer in silence, feeling shame, discomfort, and isolation during their periods. This is the harsh and often overlooked reality that many women and girls face every month in rural Isiolo.

Also Read: Best and Worst Sanitary Pads Brands in Kenya – 2025 Report

What does dignity in menstruation mean to you personally?

Dignity in menstruation means never having to go without menstrual products. It means having access to clean water, not just during that time of the month, but always.

It means having safe and private disposal facilities for used menstrual items. In essence, dignity means menstruating without shame, fear, or disruption to daily life.

Was there a specific moment or story that pushed you to start this work?

My work in advancing menstrual equity was deeply influenced by a visit to rural Isiolo, where I witnessed, first-hand, the inequalities faced by menstruating women and girls in the region.

What struck me most was how something as natural and routine as menstruation had become a major barrier in their lives, not because of the biological process itself, but because of the lack of support, resources, and education surrounding it.

To many, menstruation might seem like a minor issue, but it is a critical cog in a much larger system that continuously disadvantages women and holds them back. When we fail to address these “small” injustices, such as access to menstrual products, water, and private sanitation facilities, how can we expect to solve the larger systemic issues like corruption, climate change, or gender inequality?

As a nurse, how have your interactions with patients shaped your views on menstrual health?

My experience as a nurse has given me a unique and sometimes painful insight into how menstrual health is misunderstood, neglected, and even stigmatised.

I have cared for patients suffering from menstrual disorders who had no understanding of what was happening to their bodies. Some of them genuinely believed they were cursed, simply because no one had ever explained to them what menstruation is, or what conditions like endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome entail.

I have also witnessed how the medical system can fail these women.

Many healthcare workers, including both doctors and nurses, have been trained to dismiss period-related symptoms as “normal” pain, instead of exploring them further. This lack of attention means patients are often left without a proper diagnosis or any understanding of how their menstrual health impacts their fertility, emotional well-being, or physical changes.

That is why menstrual health education is so critical. We need to normalise conversations around menstruation, in every setting from schools and homes to clinics and policy rooms.

Only when we talk about it openly can we truly begin to understand it, and more importantly, change the systems that have ignored it for far too long.

What are some common myths or taboos around menstruation that you’re working to dismantle?

I have interacted with people who believe that menstruation is dirty and impure, and during that time of the month, they should hide and not be seen.

I have met people who thought menstruation was a disease, and whoever was touched by a menstruating woman would die.

This is how bad myths about menstruation are; until we demystify these myths, our young girls will never learn to love and respect their bodies wholly and take care of themselves accordingly.

Also Read: Makueni Bans Women on Monthly Periods from Fetching Water

How do you start conversations about menstrual health in spaces where it’s still considered “shameful”, especially in your community?

I have learned that the best way to start conversations around menstrual health is by meeting people where they are, beginning with what they already know and slowly introducing what they may not understand or feel uncomfortable discussing.

I approach these sessions much like a sermon and start by speaking about how God created every human being perfectly, regardless of their size, colour, or background. This familiar and spiritual context helps create a safe and open environment.

From there, I gradually guide the conversation toward menstruation, explaining that it too is part of God’s creation and a natural, necessary function of the female body. I draw connections between menstruation and pregnancy, helping people understand that, just as children are seen as blessings, menstruation, which makes pregnancy possible, should also be regarded as a blessing.

This method has been incredibly effective. It allows people to view menstruation through a spiritual and respectful lens, and helps dismantle shame with understanding. Many women and girls leave these sessions feeling empowered, uplifted, and with their self-esteem restored. They begin to see themselves as honoured and purposeful, not ashamed of something so natural.

You often tie menstrual health to economic empowerment. How are the two linked in your day-to-day advocacy?

In our efforts to promote empowerment, we often talk about reaching one’s full potential. But to achieve that potential, every individual, especially women, needs necessities: a roof over their head, food on the table, and peace of mind.

Peace, in this case, comes from comfort. And a woman who is bleeding through her dress while trying to earn a living does not experience peace or comfort.

For women to truly begin the journey of empowerment, they must first be comfortable physically, emotionally, and socially. Women who cannot afford menstrual products may feel forced to stay home from work or school out of fear or shame, which in turn prevents them from contributing to their communities and building their futures.

Similarly, women without access to menstrual hygiene information, clean water, or proper disposal facilities are placed in a disadvantaged physical and psychological position. That is why I believe menstrual health and economic empowerment are deeply interlinked because dignity, knowledge, and access are prerequisites for meaningful participation in society.

What role does education play in your work, and how are you helping to keep girls in school during their periods?

Education is central to everything I do. Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world,” and I truly believe that.

If we educate communities, we begin to erase myths and taboos surrounding menstruation. People start to understand that it isn’t a curse, an illness, or something to be ashamed of; it’s a natural part of life.

To help girls stay in school during their periods, I distribute sanitary pads to students, advocate for better menstrual hygiene practices, and evaluate existing policies to push for improvements, such as strengthening the government’s sanitary pad distribution program.

The goal is simple: to ensure girls never have to miss school because of something so manageable.

What kind of community reactions have you faced, both positive and challenging?

One of the most memorable and positive community experiences I have had was during the DDI Road Trip for a Cause in 2024, when we visited Naatum village. I was tasked to educate women and girls on menstrual health.

Although language was a big barrier, we met a young girl who helped translate my training session from Swahili into the local dialect.

I explained the menstrual cycle in the simplest terms possible, helping them understand what causes the symptoms they experience each month. I also shared practical tips on maintaining hygiene, changing pads, and safe disposal using what was available in their surroundings.

At the end of the session, we distributed reusable sanitary pads, a vital resource in an area so far from town and with limited access to menstrual products. The gratitude they expressed was overwhelming. They told me they had never encountered someone so confident, practical, and relatable, and that left a lasting impact on both them and me.

On the other hand, one of the most difficult moments I have faced came during a pad distribution program I organised in the same year.

Due to limited resources, I could only donate to the girls most in need. Every story I heard was heartbreaking, every girl’s situation deeply urgent. Yet, I was forced to make difficult choices and could not assist everyone.

It was one of the most emotionally taxing experiences of my work, knowing that the need is so great, and my resources sometimes so limited.

What is the one moment where you saw a real transformation in a girl’s life thanks to your work.

In 2024, a company reached out with the generous offer of donating reusable sanitary towels for distribution in my community.

As part of that initiative, I set out to identify young girls who were most in need. I met a 15-year-old girl who was living with her aunt. She had never felt comfortable enough to ask her aunt for menstrual products.

Out of desperation, she had entered into a relationship with a 20-year-old man, not because she liked him, but because he bought her sanitary pads each month.

When I gave her a pack of reusable sanitary towels, she looked at me with relief and said she would leave him immediately because she no longer needed to depend on him for something so basic. That moment has stayed with me.

I was grateful to have crossed paths with her and to have offered something that gave her freedom. But it also opened my eyes to how many other girls may be in similar or even worse situations, trading their safety and dignity for something as essential as menstrual products.

It reminded me why this work matters so deeply.

How do you collaborate with local schools, leaders, or even men in the fight against menstrual shame?

I work closely with local schools to equip teachers with the knowledge and tools they need to deliver menstrual health education in a way that is accurate, sensitive, and empowering.

I also encourage both girls and boys to speak openly about menstruation. It’s a natural process, not something to be hidden or feared.

With community leaders, my role often involves offering support in raising awareness, advising on how marginalised communities like mine can benefit from systemic reforms, and undertaking research to provide data that informs policy.

When it comes to men, I make it a point to involve them in the conversation. By doing so, we set an example for young boys and other male community members, teaching them that menstruation is normal and should never be stigmatised.

If you had unlimited resources for a menstrual health program, what would it look like?

If resources were unlimited, I would make sure no woman or girl ever lacked menstrual products. I would ensure that comprehensive information about menstruation was freely and widely accessible.

I would build disposal facilities in every community and guarantee that every toilet had a constant and clean supply of water. Every girl deserves to menstruate with dignity, and such a programme would make that possible.

What are your dreams for young girls growing up in Isiolo today?

I dream of a future where girls in Isiolo grow up without lack.

I want them to live in a system that already recognises and meets their needs, where they receive without needing to ask, because they’ve already been accounted for.

Often, marginalised communities like mine are left out of national planning and policy conversations until someone speaks up. I want these girls to grow up never knowing what it feels like to be excluded, overlooked, or unheard.

I want them to know they matter.

Who has been your biggest cheerleader or support system in this journey?

Beyond my family, my greatest support has come from the Nguvu Collective. They have walked with me through the toughest moments, even when I wasn’t sure what direction to take.

They believed in my potential before I fully saw it myself and helped me shape my dreams into actionable goals, and that support has made all the difference.

And finally, Amina, what keeps your fire burning, even on the hardest days?

Some people say leaders are born. Others say they are made. I believe both can be true. But no one ever took my hand and said, “Amina, this is the path I choose for you.” I carved my own path, often in the absence of visible female leaders from my community to look up to.

That is why I strive to be the role model I never had. I want to be someone the young girls of Isiolo can see and believe in.

What fuels me is the desire to challenge and change the systemic injustices that hold women and girls back. I look forward to a world where women don’t have to fight just to be heard, where their voices are welcomed, respected, and celebrated.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.