The passionate hopes for transformed lives and democracy that swept across pre-Independence Africa were mostly dashed within years.

Among the many causes were the imperial powers: they were leaving the continent as the cost of maintaining direct rule was financially and politically too costly, but they wanted to hold on through other means the enormous benefits the colonies provided.

Broadly speaking, they pursued this goal by offering significant development support for countries and included political and security support to the leaders themselves in the difficult and potentially unstable transition period of heightened economic expectations.

The governor general-to-be Malcolm MacDonald spent time with Mzee Jomo Kenyatta to that end, hoping he would abandon the nationalist policies he had espoused in the 1950s.

Of course, Mzee had many other reasons to forego those policies, and he did.

But where leaders were not cooperative, the former colonialists tried to hold on to their privileges in other ways.

In the Congo, Patrice Lumumba was killed, while later in Ghana and Uganda, Kwame Nkrumah and Milton Obote were undermined, and eventually deposed by their generals.

Mostly, however, many independent regimes themselves proved incapable of meeting their new challenges and people’s expectations.

In many countries, fabulously wealthy elites were being corruptly created amid intensifying poverty, with governments either becoming dictatorial or murderous to contain dissent — or the military would step in — which often added mass political violence to the brew.

A few coups were led by army officers genuinely interested in pursuing radical reforms in favor of the poor, such as General Murtala Mohammed in Nigeria and Captain Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso. Their promising reigns were cut short through assassinations.

One of the very few who somehow managed to complete his mission was Jerry Rawlings.

In the chaotic and impoverished Ghana of 1979, as a flight lieutenant aged 31, he tried to overthrow the government and was sentenced to death.

Fellow junior officers rescued him from jail in a spectacular raid just before he was to be executed. A few months later, he led a successful coup and came to power.

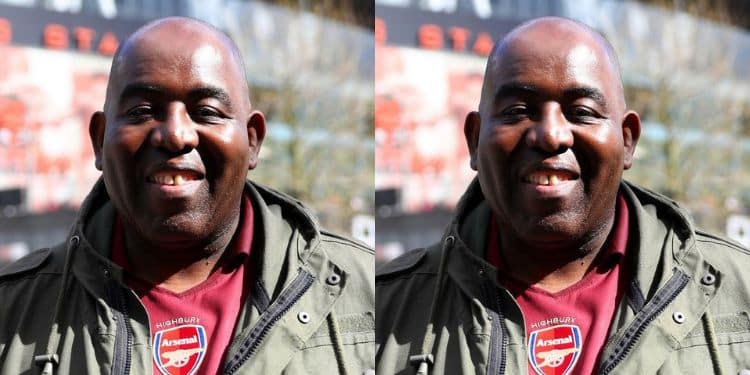

Overcoming enormous hurdles, he managed in the next 20 years to dramatically uplift his people’s economic well-being while simultaneously entrenching democracy and free and fair elections from 1991 on – Ghana’s clean elections are still the envy of all Africa.

Objectively, no other African leader in the last 40 years has managed to radically transform the economy and political freedoms as did Rawlings.

But his leadership did not escape some of the terrible contradictions that bedevil Africa and seriously undermined his early legacy.

These included executing two former presidents and four other officials in the early 1980s after they were found guilty of corruption, a vice Rawlings believed was the most damaging to a nation’s well-being.

I did not know how resonantly Rawlings lived on even in Kenyans’ imagination a full two decades after he retired from Ghana’s leadership in 2000.

On the day of his death, I did a simple two-sentence post of my view of Rawlings on Facebook. I was stunned that it elicited nearly 500 ‘reactions’, including lively debates about his legacy.

That was astounding for my small social media presence (except during Kenya’s elections, of course!). I was really pleased: Kenyans and Africans do not easily forget even distant heroes.

As it happens, Rawlings had a soft spot for Kenya as well. A profound pan-African in the Nkrumah mould, and committed to African liberation, he named his only son after Dedan Kimathi, the leader of our anti-colonial armed struggle – rather than after one the much better-known African presidents.

His Kenyan connection helped him take to me when we first met in Accra in 1988.

I myself had been a fan of Rawlings from his very early days. My deep respect was cemented when an hour-long discussion I had organized for 10 senior western correspondents whom I had brought to Ghana ended up lasting four intense, unscripted hours in Accra’s Osu Castle (State House) in 1988.

As the Chief of Information of the United Nations Africa Recovery Programme, I had taken the correspondents to observe first-hand the impact the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programmes were having on urban workers, farmers and the poor in Ghana and Senegal.

A number of African leaders from Rawlings’ time or after have had impressive successes too. Ethiopia’s Meles Zenawi did wonders for the economy, lifting millions out of poverty and linking up distant parts of the country through major infrastructure projects.

Muammar Gaddafi toppled a corrupt monarch and dramatically lifted Libya’s economic fortunes while simultaneously ensuring the country’s wealth was well deployed in services and distributed to Libyans.

Yoweri Museveni and Paul Kagame took power at unimaginably low points after the horrendous internal brutality of a vast genocide and Idi Amin’s barbarity, and brought economic and political stability — but quickly became tyrants.

We celebrate Tanzanian leaders who have maintained the exceptional stability Mwalimu Nyerere bequeathed the country.

There were also grander presidents like Nelson Mandela, Samora Machel and Joaquim Chissano, who achieved miracles amid extreme adversity.

In Kenya we have great political freedoms and highly skilled, youthful whiz kids and entrepreneurs who compete internationally — but we also have ceaseless political turmoil, extreme inequality, corruption, and lousy elections.

No African leader radically transformed the economy and political freedoms.

How did Rawlings do it?

Rawlings was politicized early by the mass Ghanaian suffering he saw and the government and the elite’s utter disregard of it. So in the Air Force when he was 30, Flight Lieutenant Rawlings joined the Free Africa Movement of junior revolutionary officers inspired by Nkrumah’s vision of Pan=Africanism, which they had taken one step beyond.

Believing that only a united Africa could fight poverty and be strong enough to tackle imperial interests, they committed themselves to forcibly removing corrupt national leaders. The radical pro-people views from a charismatic and fiery speaker endeared the youthful leader to the masses of Ghanaians, and his early successes saw his fame spread across the continent.

Coming to Power

Rawlings’ Pan-Africanism was deeply felt. As his semi-critic, Nii Ntreh of Face2Face Africa, wrote last week, he “fiercely plugged Pan-Africanism wherever he could, to the delight of [arch Pan-Africanists] Muammar Gaddafi and Nelson Mandela.”

After being freed from jail, Rawlings’ group shortly thereafter overthrew the military regime, but quickly handed over power to a civilian government that won the election they organized.

But the government totally failed to stanch the chaos, the economy plunged into incoherence and plunged Ghanaians into even deeper impoverishment.

Convinced now that even ‘democratic’ governments were incapable of national stewardship, Rawlings overthrew the government two years later, on December 31,1981, and took over the reins of power.

During the next 20 years, he worked obsessively to bring about a grassroots-oriented democracy committed to devolving genuine control and resources to the regions. Through this process, he brought deeply marginalized populations and communities into governance.

His other exceptional legacy is genuinely free and fair elections that still remain elusive on the continent.

Paying this tribute does not mean I am unmindful of Rawlings’ failures, or of the fact that many people hold very different perspectives of him.

As a writer who knew Ghana and Rawlings told me after his death last week, “Rawlings had a burning sense of Ghanaian society’s inequality and injustice, and identified with the young soldiers who desperately wanted change, for Ghana and for Africa. But over the years in power, his own lack of discipline and patience, as well as relentless external destabilization, undermined his dreams of becoming a leader like Nkrumah.”

Rawling held ‘military’ power for a decade, till 1991, and managed to restore a level of economic and political coherence that Ghanaians had not seen since Nkrumah’s early days.

It was authoritarian rule that saw the evisceration of many liberties mentioned earlier. But many believe motive was not the preservation of personal power but the stability and re-ordering of society in which the marginalized and the rural communities saw their lot improve significantly.

Industry and farming made gains, and infrastructure growth had begun to connect distant areas that hitherto had little connection to government services.

I believe this was the majority Ghanaian view, as the economic and political outcomes Rawlings delivered saw him decisively win the 1991 and 1996 multiparty elections. Having served two terms, he did not stand in 2001, and his chosen candidate to succeed him, John Ata Mills, lost that election.

As Prof Emeritus Jeffrey Haynes of London Metropolitan University has written, this was not simply a case of an authoritarian regime trying to legitimize itself by dubious elections, as contemporaneously happened in Kenya in the 1990s.

It is interesting to note Ghana under the socialist-inclined Rawlings in the early 1980s had opposed the SAPs (Structural Adjustment Programmes), as he considered them, as did many at the United Nations, as detrimental to national well-being.

But failing to generate growth without external assistance, he was forced to sign on to World Bank/IMF’s conditionalities and the economy did make significant gains for most Ghanaians.

Farmers and rural workers became more economically integrated and their incomes rose. But SAPs had a negative impact on the incomes of the urban population and market women, which saw resistance from these two influential groups rise, leading to Rawlings’ crackdowns.

In purely objective terms, Rawling’s contributions to sustained political freedom and economic stability still evident a full 20 years after he gave up power voluntarily are unchallenged.

That these are not fully acknowledged universally is due in part to his mercurial temperament, as well as his lack of an elite Ghanaian education.

This led to many traditional opinion-making power center’s and opinion makers not offering Rawlings the full acceptance he so ardently desired.

Thankfully, it did not deter him from pursuing his goals.