Kenya’s presidents have a long history of falling out with their deputies – Rigathi Gachagua’s impeachment would be no surprise.

The process of removing Kenya’s deputy president Rigathi Gachagua is part of a long history, dating back to independence, of fallouts between the president and his deputy. The difference this time around is the process.

Historically, presidents have fired their deputies. But the adoption of a new constitution in 2010, saw the introduction of a process for impeachment – for both the president and the deputy – that’s run by the legislature. This is the first time it’s been used.

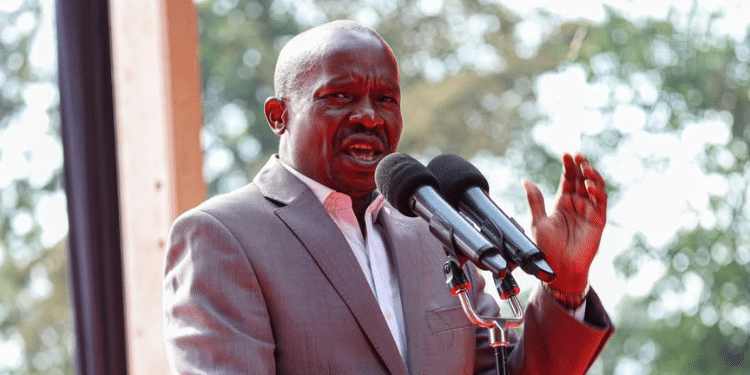

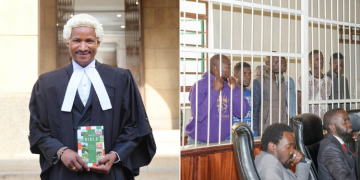

On 8 October 2024, members of Kenya’s national assembly voted to impeach Gachagua on grounds that included corruption, insubordination and ethnically divisive politics.

The case now moves to the senate where members will hear the charges – and Gachagua’s defence – and vote.

If at least two-thirds of senate accept the charges, and Gachagua’s legal challenges fail, then Gachagua will make history as Kenya’s first deputy leader to be impeached.

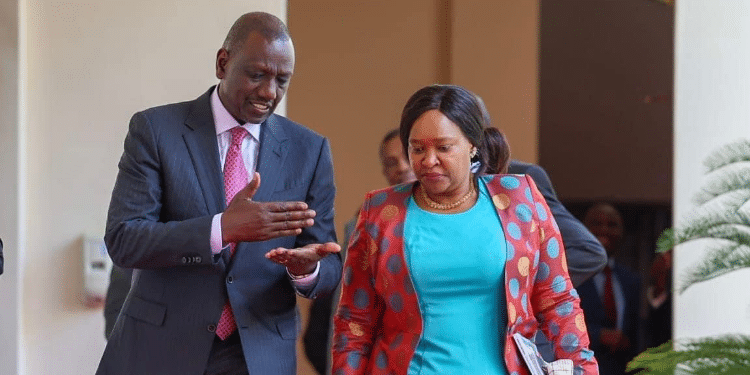

So far, President William Ruto has stayed silent on the matter, but the process would not be proceeding without his blessing.

Amid the novelty of the impeachment process, it’s easy to forget that it is the norm for Kenyan presidents to fall out with their deputies. As a political scientist interested in Kenya’s ethnic politics and democratisation, I argue that this is because of how deputies are selected in the first place.

Deputies are initially selected largely on pragmatic grounds as people who bring something useful to a political alliance. This could be resources, a support base or a reputation for being a good technocrat or administrator.

They’re not usually people with whom the president has a strong and continuous personal relationship or someone with whom they share a clear political ideology. Neither are they usually someone who has made their way up through a political party.

This has brought about a long history of tensions and fallout between Kenya’s presidents and their deputies.

History of fallouts

Independent Kenya’s first vice president, Oginga Odinga, saw his ministerial portfolio gradually reduced by President Jomo Kenyatta. Kenyatta then replaced Odinga as vice president of the ruling Kenya African National Union (Kanu) in 1966 further undermining his powers.

Soon after, Odinga joined the opposition Kenya’s People’s Union.

His successor, Joseph Murumbi, resigned within months. The official reason given was ill health, but it is widely believed that Murumbi was troubled by corruption and authoritarianism within the Kenyatta regime.

Kenya’s second president, Daniel arap Moi, elected Mwai Kibaki as his first deputy. Kibaki was dropped after a decade. He went on to form an opposition party as soon as Kenya shifted to multi-party politics in 1992.

Moi’s second vice president, Josephat Karanja, resigned after a year to avoid a vote of no confidence for allegedly plotting to overthrow the government.

Moi’s third deputy, George Saitoti was sidelined to pave way for Uhuru Kenyatta’s nomination as the party flagbearer in 2002. Moi’s final deputy, Musalia Mudavadi, fell with the rest of the Kanu government in the 2002 elections.

As Kenya’s third president, Kibaki similarly oversaw a regular change of guard. His first deputy, Michael Wamalwa, died after a few months in office. His second, Moody Awori, lost his seat in the 2007 election.

Kibaki’s third deputy, Kalonzo Musyoka, joined the president during Kenya’s post-election violence of 2007-08. He left at the end of his term in 2013 to run with Raila Odinga in the 2013, 2017 and 2022 presidential elections.

Kenya’s fourth president, Uhuru Kenyatta, was the only leader to have the same deputy, William Ruto, for his full term as president – from 2013 to 2022. However, relations between Kenyatta and Ruto were hardly rosy.

The two fell out after the 2017 elections as Kenyatta teamed up with long-standing opposition leader, Raila Odinga. Ruto beat Odinga, Kenyatta’s favoured candidate in the 2022 elections.

Lessons to learn

Because deputies are selected for their practical value, the person who made a good deputy at one point in time can come to be seen as a liability or threat as the political context changes.

For example, at independence, Oginga Odinga made an excellent ally for Jomo Kenyatta. He had some resources and was a proven mobiliser. He brought a support base. However, within a few years, Odinga became a problem for the president as a more radical faction within the ruling party coalesced around him.

Similarly, Ruto made an excellent ally for Uhuru Kenyatta when they both faced charges for crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court. The two fell out once Kenyatta had won his second and final term, and Kenyatta turned to his succession.

Gachagua was useful to Ruto in 2022. He had personal wealth, was an effective mobiliser and hailed from central Kenya where the election looked to be won or lost. However, once elected, Gachagua’s populist statements and reputation for ethnic bias became more of a liability.

Second, as contexts change, someone else can soon come to be seen as more useful as second in command.

For Jomo Kenyatta, Moi had shown his utility and loyalty during the “little general elections” of 1966, which effectively sidelined the Kenya People’s Union and Oginga Odinga.

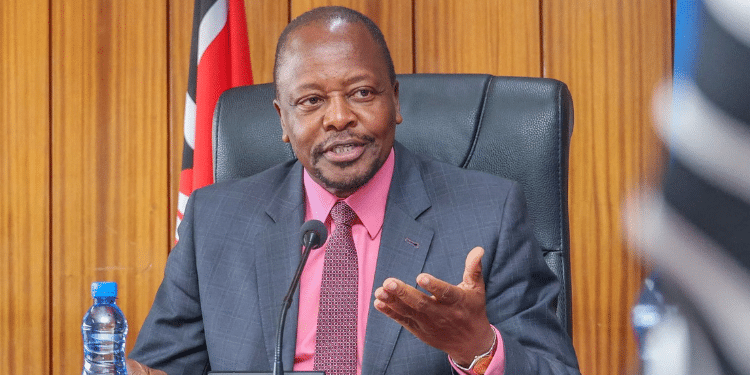

Kithure Kindiki, Kenya’s interior cabinet secretary, is the current frontrunner to replace Gachagua. He is seen as better able to negotiate with the international community, especially during a critical economic period for Kenya as it seeks new International Monetary Fund loans.

Third, being the country’s vice or deputy president comes with a lot of opportunities to network. These interactions have often led individuals to be seen as a growing threat, or as actively plotting against the president. They may also be seen as a future challenger.

History has shown that there is no ideal way of dealing with such a potential challenger, leading subsequent presidents to try different approaches.

Current context

Ruto and Gachagua have clearly fallen out. Their differences became apparent soon after the 2022 elections. However, they came into sharp relief in the face of anti-tax protests in June 2024. There were subsequent allegations that Gachagua and some of his allies had helped to finance the protests.

The question, therefore, isn’t why they have fallen out but why Gachagua is being impeached now.

Ultimately the answer to this can only be known by a few individuals. But perhaps an indication of the answer lies in the emotions the fallout has stirred: a desire to distract the public and show that the government is taking action to deal with Kenya’s ongoing economic crisis. There may also be a desire to undercut Gachagua before he can build national networks.

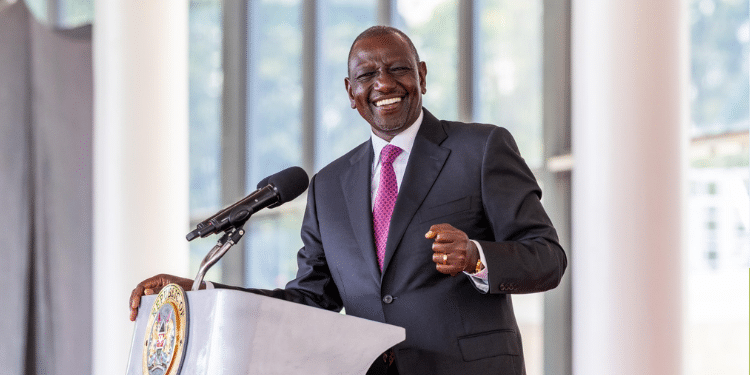

Ruto has the numbers in the senate to see the impeachment process through. But this is a dangerous game. Those sidelined have a habit of coming back to haunt their former allies.

At the moment, most Kenyans are supportive of the impeachment process, but many also feel that Gachagua is being unfairly targeted especially in central Kenya, where a majority oppose the process.

While a successful impeachment might see Gachagua barred from holding public office, this wouldn’t necessarily mean an end to his career as an effective political mobiliser.

The next few months – and the narratives that emerge about why Ruto and Gachagua fell out – will be critical in determining both their futures.![]()

Gabrielle Lynch, the author of this article, is a Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![Debate Rages Over Proposed Increase In Legal Drinking Age [Video] Nacada Raises Legal Drinking Age From 18 To 21]( https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/07/beer-360x180.jpg)

![Debate Rages Over Proposed Increase In Legal Drinking Age [Video] Nacada Raises Legal Drinking Age From 18 To 21]( https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/07/beer-120x86.jpg)