… that no man be informed of my death,

… and no man be made to grieve on account of my death,

…and I be not buried in consecrated ground,

…and no mourners walk behind me at my funeral,

… and that no flowers be planted on my grave.

Thomas Hardy

In boxing jargon, the almost four-year Russian-Ukrainian war can be compared to two punch-drunk boxers in a bout just going through the motions of exchanging punches with neither having the reserves to knock out the opponent.

This state of affairs partly explains why the two nations at war are desperate for recruits. It also explains why the social media in Kenya is awash with proven evidence that several Kenyans have travelled to Eastern Europe and have been recruited by either Russia or Ukraine as soldiers for hire. So far, there has been no official government statement on this matter. Considering the level of economic desperation in the country, it is undoubtedly true that many Kenyans will be eager to seize such an opportunity.

But who are mercenaries?

Mercenaries are privately trained protection personnel motivated by financial gain, or, in rare instances, professional soldiers hired to serve in a foreign army or militia. Unlike volunteers or regular draftees, they have no political, religious, or cultural affiliation with the nation-state they serve.

They are simply offering their expertise on a professional basis for monetary compensation. They have been called soldiers of fortune.

The earliest recorded use of foreign mercenaries dates back to ancient Egypt, in the thirteenth century BC, when Pharaoh Ramesses II employed over 11,000 Nubians as mercenaries to aid him in fighting his numerous wars.

Further North, the Punic Wars, fought between 264 BCE and 146 BCE, with Hannibal as the main prosecutor, mustered forces who were primarily mercenaries.

In the modern African setting, the most famous mercenary is “Mad” Mike Hoare, a retired British military officer who, upon relocating to South Africa, mobilised a mercenary force commanded mainly by South African veterans. Hoare’s mercenaries, known as Simbas, fought on both sides in the Belgian Congo during the early 1960s. His exploits were glamorised in the movie “The Wild Geese”

Another famous soldier of fortune was Bob Dennard, a former French special forces officer who led a mercenary outfit composed mainly of French Legionnaires. His adventures as a mercenary spanned seven African countries over a 12-year period. Dennard exploits were fictionalised in the 1973 bestseller “Dogs of War” by Fredrick Forsyth.

Eebeen Barlow is another South African Veteran, a Colonel whose mercenary outfit, Executive Outcomes, bolstered several weak but corrupt African governments, primarily in West Africa, in the late 1990s.

The Wagner Group, a Russian-supported mercenary outfit, remains active in the Sahel region, grappling with mixed results.

But who fits the mercenary calling?

In all serious standing armies, there is a breed of soldiers who are suspected of having that extra dose of testosterone, continually maintaining a regimen of superb fitness that exceeds the routine fitness expected of any fighting soldier.

They stand out as brash, reckless, brave, and maybe even stupid, as they like to live dangerously. Such soldiers, naturally, find themselves enlisted in the special forces. The world over, special forces, unlike regular soldiers, have acquired specialised training and sharpened their ability to think strategically, making them effective force multipliers.

Also Read: Russia Secretly Recruits 22 Kenyans to Fight War in Ukraine

It is such soldiers who, after a short stint in uniform, resign and find themselves forming the core of many professional mercenary outfits.

But how are the Kenyans recruited?

Recruitment in the country has apparently been done mainly through word of mouth, targeting personnel who had worked in security establishments and had experience in handling weaponry. The sales pitch may have been persuasive with a plausible layer of misinformation floated to obscure the overall purpose.

The recruiters’ sales pitch would be that the recruits were set to be deployed far from the front lines as rear-echelon personnel in the logistics corps, supporting the overall war effort by keeping the fighting soldiers fed, watered, and providing all necessary services to sustain the war.

Their deployment, the recruiter would be at pains to point out, would be well out of harm’s way and would mainly be tasked with freeing up the country’s troops from basic duties, allowing the national forces to concentrate on winning the war.

The recruiter would never dare mention the term “mercenary”. He would, however, dwell on the monetary gains to be garnered after appending their signatures on a page written in a language that the recruits don’t understand.

Upon arrival in the grim, cold country, the reality dawns on them that they are immediately outfitted in combat gear, armed, given rudimentary training, and mobilised into a fighting formation under the command of professional mercenary officers.

Unbeknownst to the recruits, their new commanders have a better understanding of the lay of the land, figuratively, and once they have deployed the new greenhorns, secretly make their planned exits.

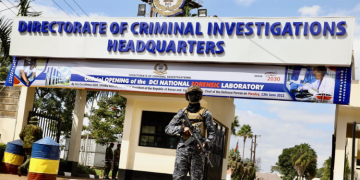

But what are the legal implications of deploying Kenyan citizenry as mercenaries?

Article 47 of the Geneva Convention states, “A mercenary shall not have the right to be a combatant or a prisoner of war”. A very grey statement indeed, as it does not prohibit one from being a mercenary, yet it prohibits one from being a combatant because, if captured, you have no rights as a prisoner of war and therefore can be tried as a civilian and a criminal.

With reports of foreign recruitment in the country, what are the likely emerging scenarios?

There are four likely scenarios: one, the recruitment pipeline will continue underground, and desperate Kenyans will likely continue to join the bandwagon and eventually end up in the war zones.

Also Read: Inside the Salary Package for Kenyans Joining Ukraine’s Army

Two, as long as the payments are constant from the war zone, the situation is bound to remain quiet.

The third scenario is likely to erupt when, suddenly, the expected stipend stops and reports start trickling in of Kenyans being seized as prisoners of war or, God forbid, having fallen on the war front.

This expected eruption invariably leads to the fourth scenario, which is an increase in national concern as calls become louder, calling for the government to make plans to repatriate the Kenyans back home.

So, what should the Government do?

The ongoing recruitment process needs to be addressed with the relevant government offices, which will assess the overall situation before making a policy decision and outlining a way forward.

Should the government decide to curtail this recruitment, few Kenyans are likely to ignore the government’s calls. There is then a probable need to have the above poem by Thomas Hardy, dubbed the Mercenary’s Prayer, advertised daily on prime-time television for potential mercenary recruits to take note of.

This article was written by Col. (Rtd) Owuoth, a combat veteran of the Somalia theatre and author of Somalia: Voices from the front.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates

I will appreciate when I have joined Russia army

I will appreciate when I have joined Russia army I will to my best to keep Russia safe