Across Kenya, the concept of a meal is deeply tied to the presence of staple foods—those central ingredients like maize, rice, or cassava that anchor every plate. Yet, beneath the surface of this culinary tradition lies a growing threat to the very foundation of Kenya’s food systems: seed and livestock colonialism. This dual menace not only endangers food security but also undermines the cultural and economic fabric that sustains millions of Kenyan families. For many, whether Christian, Muslim, or adherents of traditional beliefs, food is more than sustenance—it is identity, ritual, and comfort. And in this equation, side dishes alone cannot suffice.

Seed Colonialism: When Staples Become Out of Reach

Seed colonialism refers to the dominance of multinational corporations in seed production and distribution, compelling farmers to buy genetically modified (GM) or hybrid seeds each year. These seeds often require synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, further entrenching dependency on external inputs controlled by foreign entities. Meanwhile, traditional seed-saving and sharing practices have been criminalized through international trade agreements such as UPOV 91, which prioritizes corporate intellectual property rights over indigenous knowledge.

For Mary Wanjiku, a farmer from Embu County, the shift has been stark. “We used to plant sorghum and millet, which would survive even in dry years,” she recalls. “Now, we rely on maize, but when the rains fail, we have nothing to harvest.” Maize, now deeply entrenched as a staple food in Kenya, forms the backbone of ugali—a stiff maize flour porridge considered essential to any meal. Without it, many Kenyans feel they haven’t truly eaten, regardless of what else they consume.

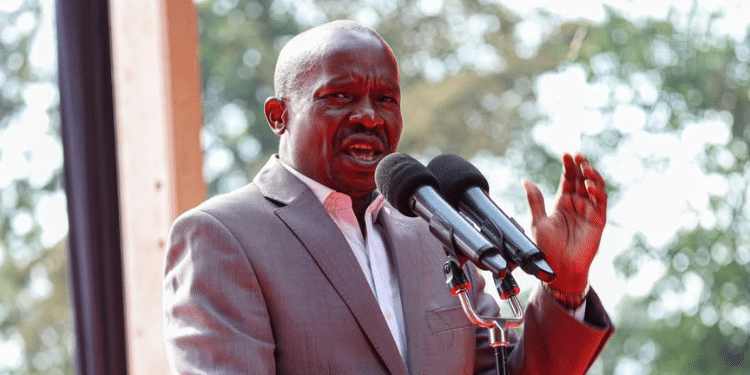

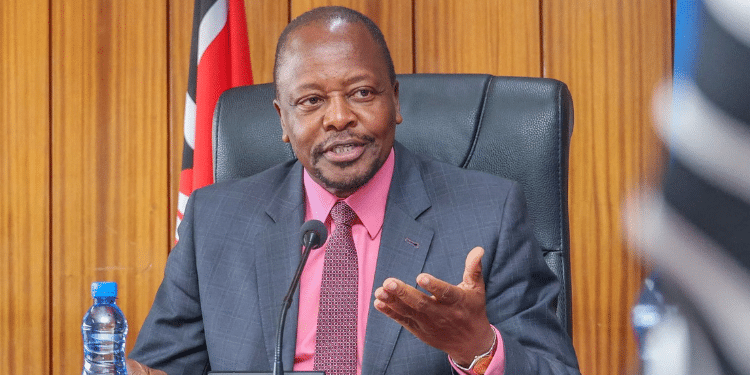

Also Read: Mutahi Kagwe’s Declaration of Water Buffalo as Food Raises Critical Questions

This cultural attachment underscores why seed colonialism is so dangerous. When multinational corporations control access to seeds, they indirectly dictate what ends up on people’s plates. The loss of indigenous crops like finger millet and teff—not only nutritious but also climate-resilient—means fewer options for communities facing increasingly unpredictable weather patterns. This is particularly felt during fasting periods, when breaking fast with familiar staples provides comfort and continuity.

Livestock Colonialism: Prioritizing Exotics Over Natives

Parallel to seed colonialism is livestock colonialism, where exotic breeds are promoted at the expense of indigenous ones. Friesian cows and Boer goats, prized for their high yields, dominate policy incentives and subsidies. However, these animals often struggle in Kenya’s harsh environmental conditions without expensive imported vaccines and feeds.

“Indigenous livestock, like Zebu cattle and Red Maasai sheep, are naturally resistant to diseases and better suited to local climates,” explains Dr. Peter Lole, a livestock researcher. Yet, policies favor exotic breeds, creating an unsustainable reliance on costly imports. For pastoralist communities in regions like Turkana and Samburu, this dependence threatens their ability to sustain herds during droughts.

The ripple effects extend beyond rural areas. Shortages caused by declining herd sizes could leave urban tables bare. Here again, the absence of familiar staples—whether ugali or hearty portions of meat—would leave consumers feeling unsatisfied, even after long periods of fasting. For Christians observing Lent or Muslims fasting during Ramadan, the act of breaking fast with traditional foods is both a physical and spiritual necessity. Without these staples, the experience feels incomplete.

When Side Dishes Aren’t Enough

In many cultures, including Kenya’s, staple foods are more than sustenance; they embody tradition, identity, and comfort. Ugali, made from maize flour, is not just a food item—it is the cornerstone of a meal. A person may eat vegetables, meat, or fruits but still claim they haven’t had a meal unless ugali graces their plate. Similarly, in parts of Asia, rice is so central to the concept of eating that a meal feels incomplete without it.

This cultural attachment stems from centuries of agricultural practice. Staple foods are typically abundant and affordable, making them the default base of meals while relegating other foods to accompaniments—or side dishes. Eating without the staple feels akin to having only “side dishes”—something lacking in fullness or substance.

Psychologically, staples provide more than satiety; they evoke comfort and normalcy. Imagine a Kenyan farmer who eats a bowl of soup but declares their stomach “empty” because there was no ugali. Or consider a Japanese office worker who opts for bread instead of rice for lunch, feeling they’ve merely snacked rather than dined. The staple offers structure—a foundation upon which the idea of a meal is built.

From a nutritional perspective, a meal without a staple can still be balanced if it includes proteins, fats, and micronutrients. However, perception often outweighs logic. Efforts to substitute staples during food shortages frequently face resistance. For instance, a community reliant on maize might reject wheat-based alternatives, even if equally nutritious. This demonstrates the emotional and symbolic value of staples, transcending their physical role in a diet.

Globally, examples abound. In the Philippines, the phrase *hindi pa ako kumain* (“I haven’t eaten”) often implies “I haven’t eaten rice.” In Mexico, tortillas made from maize are integral to every meal. In Italy, pasta or bread anchors the dining experience. And in Nigeria, pounded yam, fufu, or eba are staples that signify eating well. Without them, even lavish spreads can feel insufficient.

During fasting periods, such as Ramadan for Muslims or Lent for Christians, the absence of these staples becomes even more pronounced. Breaking fast with unfamiliar or inadequate foods disrupts the sense of fulfillment and ritual that accompanies these spiritual practices.

Bridging Tradition and Innovation

Amid these challenges, efforts to counter seed and livestock colonialism are gaining momentum. Organizations like the Kenya Biodiversity Coalition advocate for preserving indigenous seeds and livestock breeds while promoting agroecological practices. Community-led seed banks and training programs empower farmers to protect traditional farming systems.

“The future of Kenya’s food systems depends on empowering farmers and herders to reclaim their independence,” says Dr. Josephine Muli, an agricultural expert. “This means protecting their rights to save seeds, access affordable veterinary care, and maintain indigenous breeds.”

Farmers themselves are innovating to reduce costs and retain control. Charles Kimani, a Dutch-trained animal nutritionist, highlights how small-scale farmers can produce animal feeds using locally available resources like maize, cassava, or farm by-products. Large-scale farmers, meanwhile, turn feed-making into a business, proving that resourcefulness—not privilege—is key to sustaining livestock productivity.

Safeguarding Kenya’s Agricultural Heritage

The fragility of Kenya’s food systems becomes apparent as indigenous crops and livestock, resilient to climate extremes, are being sidelined by commercial alternatives that demand high inputs. This dependence threatens year-round food security for millions.

Moreover, exotic livestock strains natural resources like water and feed, worsening environmental degradation. The loss of indigenous seeds and animals reduces biodiversity, leaving Kenya less equipped to face future challenges such as droughts and climate change.

Yet, hope remains. By prioritizing local solutions and biodiversity, Kenya can secure a food system that thrives for generations to come. Safeguarding agricultural heritage ensures that staples like ugali remain accessible, allowing families to enjoy complete meals—and ensuring food security for all Kenyans, whether they are fasting or feasting.

As plates are filled and shared across the nation, let us remember: side dishes alone cannot satisfy. But ensuring those staples remain culturally relevant and environmentally sustainable requires collective action. Only then can Kenya’s food systems endure the challenges of colonialism and flourish for years to come.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and join our WhatsApp Group for real-time news updates.

![Debate Rages Over Proposed Increase In Legal Drinking Age [Video] Nacada Raises Legal Drinking Age From 18 To 21]( https://thekenyatimescdn-ese7d3e7ghdnbfa9.z01.azurefd.net/prodimages/uploads/2025/07/beer-360x180.jpg)