John Dewey, an American philosopher, is one of those great people whose thoughts on education never wither. In his 1907 book titled The School and Society he says: “What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all of its children.”

He goes on to say: “Any other ideal for our schools is narrow and unlovely; acted upon, it destroys our democracy.” This emphasis on the need for quality education holds true whether one refers to a socialist or a capitalist oriented society, or to other ideological variants.

In line with those thoughts, I suppose in Kenya we are agreed that education is the cornerstone of a nation’s progress, a foundation upon which the future workforce, leaders, and innovators are built.

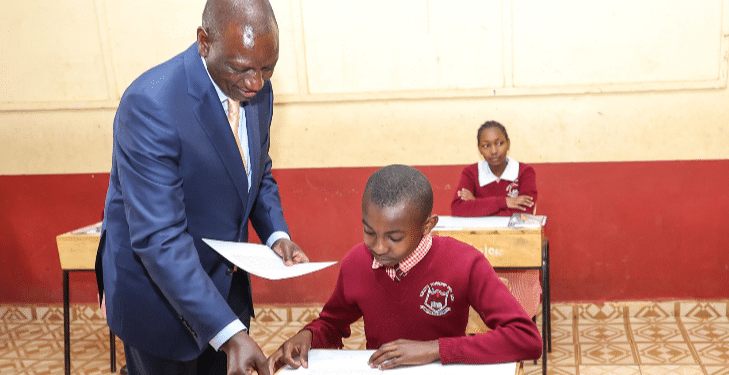

Over the last nine years, our government embarked on an ambitious education reform by transitioning from the 8-4-4 system to the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC). The aim was — and still is — to address the gaps in skill acquisition and adaptability that plagued the old system.

However, as the pioneer group of the CBC transitions to Grade 9 in less than two months from now, the reform process remains marred by significant challenges that continue to raise serious concerns among stakeholders.

The question of where to house Grade 9 students—in primary or secondary schools—is just one representation of the broader issues facing the CBC’s implementation.

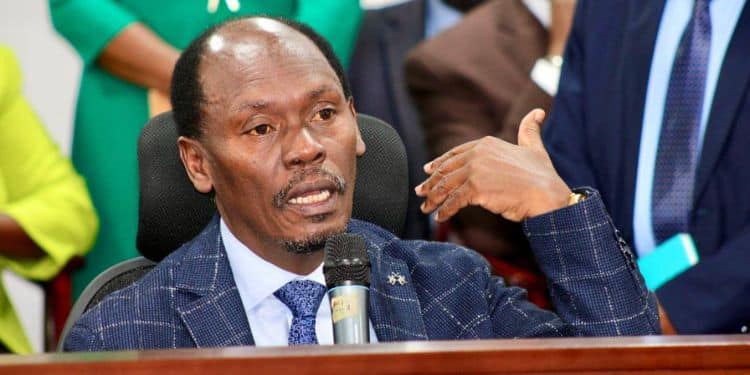

Lately, the government has insisted that the venue of Grade 9 students will remain in primary schools where they took their Grade 7 and 8 studies. However, some stakeholders have divided opinions on the matter. Even within the government, some educationists have had different opinions while others were just unsure where the class should be placed. However, they know well that they have to toe the official government line.

As Form 1 rooms turn idle in Jan, Grade 9 to grapple with crowding

This confusion on where ninth graders are to be hosted is a symptom of the poor handling of education sector reforms. Despite initial projections and plans, coupled with hours of expensive sittings in workshops in big hotels, the government has failed to create a clear, cohesive strategy, leading to embarrassing uncertainties. The use of vacant Form 1 classrooms in secondary schools, for instance, is logical yet unaddressed, illustrating how a lack of foresight can compromise the welfare and rights of the children.

Also Read: Ministry of Education Clarifies Fresh Changes to CBC Program

That is why philosopher and educator John Dewey is right in saying that “what the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all its children.” At this juncture one is poised to ask: if education is not prioritized, what kind of future is the country preparing for its young citizens?

What concerns me as a citizen and keen observer is that the CBC’s implementation has suffered too many drawbacks – some of them incidental and others systemic, some resulting from sheer oversight while others stem from state neglect. Staff shortages, inadequate teacher orientation, and a severe lack of facilities and learning materials have left reforms on shaky ground.

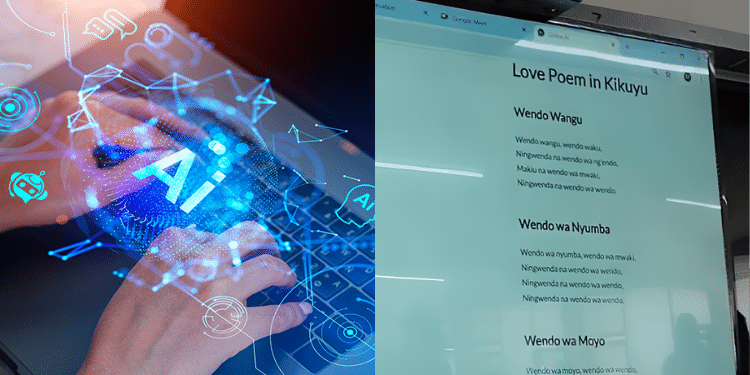

Further, the expectation that teachers would seamlessly adapt to a fundamentally different curriculum without thorough and sustained training has exposed a major flaw in the reform strategy. In reality, teachers—the backbone of educational success—have often found themselves under-resourced and underprepared, leading to disjointed learning experiences for students.

Ninth year into the CBC-based reforms, one would expect more progress. Sometimes, stakeholders seem to read from different scripts courtesy of skewed information dissemination, which worsens an already bad situation, leaving many parents, teachers, and administrators unsure of their roles and responsibilities. This information gap wears out the level of public (stakeholders’) trust and undermines unity of purpose in the reforms process.

How education sector crisis mirrors health sector crises

When implementing education that is competence based, the implementers should always exhibit competence lest citizens lose confidence.

The root of these challenges appears to lie in the government’s commitment—or lack thereof—to public education. There is a pervasive belief that decision-makers remain detached from the struggles of public schools, as many can afford expensive international education for their own children. This detachment is mirrored in other public sectors, such as healthcare, further eroding public confidence.

The CBC transition to senior secondary, and eventually to tertiary education, risks being dogged by the same unresolved issues seen today. If urgent action is not taken, Kenya faces a bleak future where dashed hopes and a fractured education system undermine national progress. This outcome would be tragic, considering that we all know the purpose of CBC is to foster holistic, skill-oriented learning. The sight of unoccupied Form 1 classrooms while Grade 9 students scramble for space in ill-equipped primary schools symbolizes the inefficiency and half-hearted execution of these reforms.

Also Read: Plan to Roll Out CBC in Universities Countywide in Top Gear

Way Forward

To steer the CBC reforms toward success, the implementation team must be more visible and actively engaged with all stakeholders. Genuine partnerships between the Ministry of Education, teachers’ unions, parents’ associations, and community leaders are essential to ensure seamless communication and most importantly action on the feedback from different stakeholders. Engaging stakeholders should not be seen as a favour or act of generosity by those at Jogoo House. Neither should they see criticism as detraction.

The government needs to demonstrate commitment to resolve the problem of shortages of staff and resources. More teacher orientation programs are called for so as to align their teaching methods with the principles of CBC, which is supposed to be learner centred rather than teacher cantered, focused on discovery rather than rote memory, and based on individuality rather than competition. The time for addressing issues of staff, infrastructure, and materials is now, as students, parents, staff and other stakeholder have persevered enough promises.

When launching an outfit called Mindset Network in South Africa back in 2003, former president Nelson Mandela noted that “education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” Here at home, it behoves upon our government and all stakeholders of education to demonstrate that CBC is more than just a policy on paper. Let’s end confusion in its implementation now.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and join our WhatsApp Group for real-time news updates.