The horror on the ground: On February 11, 2025, Kenya woke to one of the most chilling stories in recent memory. In Githogoro, near Runda, a woman named Monica allegedly killed her three children with bedsheets before hanging herself.

She left behind an eight-page note.

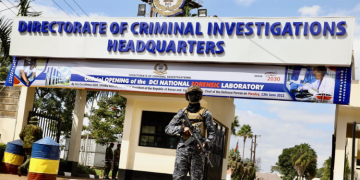

Her husband, returning from a night shift, found the lifeless bodies and raised the alarm. Neighbours poured in, police followed, but all they found was horror.

Barely three months later, in May 2025, police recorded multiple suspected suicides across the country in a single day.

In Nairobi’s Kahawa West, 28-year-old Henry Ndika was found dead in his locked house.

In Nyeri, 34-year-old Winfred Wangari’s body was discovered in her home.

In Baringo, a 55-year-old woman named Cecilia Ruto was found hanging from a tree.

In Migori, 25-year-old Julius Magina was found hanging inside the house.

And just weeks ago, on September 22, 2025, the body of 34-year-old Aisha Kajuju was found in Mihango, Nairobi.

She had sealed her house with tape and wet clothes before lighting a jiko. It was her third attempt. This time, she succeeded.

These are not distant headlines. They are our neighbours, our friends, our families.

Every week, Kenyan newspapers carry these grim stories. Each death is a scream in the dark, and yet we move on as though it were inevitable.

Suicide Global picture

Globally, more than 700,000 people die by suicide every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). That is one person every 40 seconds.

In Kenya, the Ministry of Health estimates about four deaths every single day, and those are only the reported cases.

Suicide is now the fourth leading cause of death among young people.

Also Read: Wives Beating Husbands in Mt. Kenya Pushing Men to Die by Suicide, Chief Lifts Lid

Men are disproportionately affected; nearly three-quarters of cases are male, from teenagers to retirees.

The World Bank places Kenya’s suicide rate at 6.1 per 100,000, higher than India and Mexico. Men are hit hardest, with 9.1 cases per 100,000 compared to 3.1 for women.

This is not a coincidence. It is a national emergency hiding in plain sight.

In a society that prides itself on being religious and community-based, how is it that despair has become this common?

How can a nation of churches, mosques, chamas, and ‘family-first’ produce so many lonely deaths?

Root Causes

The causes are not mysterious.

They are written in our headlines and our households.

Mental illness, untreated and hidden, festers because counselling is expensive, psychiatrists are few, and stigma is everywhere.

Depression is dismissed as “laziness.” Anxiety is mocked. Trauma is silenced.

Economic despair drives many to the edge.

When a father cannot provide, when a young graduate sends CVs for years with no reply, when debts choke and hustling no longer sustains, suicide becomes the “way out.”

Poverty is not just a statistic; it is a daily humiliation that crushes dignity.

Substance abuse fuels the spiral.

Cheap alcohol and drugs numb the pain but deepen the void. And when the intoxication clears, the noose or pesticide waits.

Family and relationship breakdowns add to the storm.

Also Read: CCTV Captures Moment of Pedestrian Attempting Suicide Before Being Struck by Vehicle

Domestic violence, land disputes, separations, and gender-based conflicts are common in police reports.

These intimate failures cut deepest because they happen in the very spaces where people expect refuge.

And then there is the cruelty of the law itself.

Until 2023, Kenya criminalised attempted suicide.

Imagine waking up in a hospital bed after trying to end your life, only to be handcuffed. That is not prevention, that is cruelty dressed as law.

Kenya’s structural failures

This is not just about individuals making desperate choices. It is about a system that abandons its citizens.

Kenya has fewer than 100 psychiatrists for 50 million people.

Counsellors are concentrated in cities.

Rural communities are left with pastors, herbalists, and silence.

Schools have no mental health programmes. Workplaces treat stress as weakness.

Our public health system barely acknowledges mental health.

Churches preach hope while ignoring the desperation in their pews.

Politicians shed crocodile tears when a tragedy goes viral, then move on to the next rally.

The hypocrisy is unbearable.

We preach “family first,” yet families cast out children who fail exams, women who cannot bear children, or men who cannot provide.

We praise masculinity, then mock men when they cry. We recite Bible verses about comfort, then condemn those who seek help.

Hope

In 2023, Judge Lawrence Mugambi struck down Section 226 of the Penal Code, declaring it unconstitutional to criminalise attempted suicide.

Doctors like Mathari Hospital’s Dr. Julius Ogato remind us that just as diabetes comes from an insulin imbalance, suicidal thoughts come from a chemical imbalance. They require empathy, treatment, and support, not condemnation.

Kenya’s Suicide Prevention Strategy (2021–2026) acknowledges the scale of the crisis. Hotlines exist: Befrienders Kenya (+254 722 178 177), Red Cross (1199).

These are important, but how many rural youths are aware of their existence? How many can afford the airtime when calling itself is a luxury?

The demands

Every statistic is a grave.

Every “case file” is a father, a mother, a child, a neighbour. And every death is an indictment of our silence.

We bury the bodies, whisper condolences, move on, and wait for the next obituary.

Kenya can no longer afford this cycle.

We cannot keep condemning despair while investing almost nothing in mental health.

We cannot claim to be religious and community-driven yet shun those most in need of compassion.

We cannot pretend suicide is “personal weakness” when it is in fact the mirror of our national failures.

Kenya must face its suicide crisis as a national emergency.

This is not about awareness days or hashtags.

It is about funding mental health care, hiring professionals in every county, integrating counselling into schools, and building community-based support.

It is about creating jobs, easing economic despair, and treating poverty as suicide prevention.

We must confront our cultural hypocrisy. Stop shaming men for being vulnerable, stop silencing victims of abuse, stop burying the issue under prayers and platitudes. Faith without structural action is empty.

Kenya can no longer criminalise despair, whisper condolences, and move on.

Every suicide is an indictment.

Every death is a question we keep refusing to answer. And if we keep ignoring it, the graves will keep filling.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.