“Voting is your civic duty” is a familiar catchphrase. But its true weight is only understood through the long, hard-fought struggle for that right. While every Kenyan over 18 now holds this power, our history shows a journey from brutal exclusion to hard-won suffrage, a journey today’s generation must honour with action.

A Journey of Exclusion and Struggle

Before colonization, Kenyan communities did not have a Western-style voting system. Governance was typically exercised through councils of elders (e.g., the Kiama among the Kikuyu, or the Laibon among the Maasai), where leaders were chosen based on lineage, wisdom, age, and wealth, rather than universal suffrage. (One person, one vote).

The British colonial regime then introduced a Western-style system designed to exclude. Initially, it was a club for white settlers, with the first members being appointed by the Governor. There was no voting for Kenyans.

Its purpose was to advise the Governor on the administration of the colony, primarily serving the interests of the European settlers.

Also Read: IEBC Announces Leading Counties in Voter Registration Turnout

A shift began in 1944 with Eliud Mathu, the first African member of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Later, the 1954 Lyttelton Constitution allowed the election of African representatives, but under separate racial rolls: Europeans, Asians, and Africans voted for their own representatives. The franchise was extremely limited.

To vote, an African had to meet stringent criteria, including proof of literacy. Income requirements. Ownership of property. Long-term residence. Voting was thus a privilege for a small, “qualified” elite loyal to colonial rule.

The turning point came in 1957 with the first direct elections for African representatives. Though the racial rolls remained, this election galvanized the nation.

Leaders like Tom Mboya, Oginga Odinga, and Ronald Ngala were elected and used their platforms to aggressively demand independence.

This marked the birth of mass-mobilization politics and cemented the cry for “one person, one vote” as the central pillar of the liberation struggle.

That dream was realized with the 1963 Independence Constitution, which established universal adult suffrage for all citizens aged 21 and over.

The first general elections were hotly contested, with KANU defeating KADU. Yet, this hard-won freedom was soon curtailed.

By 1969, Kenya became a de facto one-party state under KANU.

The constitution was amended in 1982 to make this official, legally outlawing opposition.

Voting continued, but its essence was stripped away.

The presidency became a mere “Yes” or “No” affair for the sole candidate.

Elections were reduced to intra-party competitions, marred by fraud, a lack of a secret ballot, and state-sponsored harassment.

The vote was no longer an exercise of choice but a ritual of loyalty, a hollow echo of the democratic promise of 1963.

Kenya’s Second Liberation

Pressure for change, the “Second Liberation”, forced President Moi to repeal the one-party law in 1991.

Multi-party politics returned, but the 1992 and 1997 elections were deeply flawed, featuring violence, ballot-box stuffing, and a biased electoral commission. A divided opposition allowed KANU to cling to power with a minority of the vote.

The 2002 election was a landmark. KANU lost power peacefully. But hope collapsed in 2007. The Electoral Commission’s opaque declaration of Mwai Kibaki as the winner sparked catastrophic violence.

Over 1,100 lives were lost, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. That national tragedy exposed the rot in electoral governance and became the painful catalyst for a new constitution.

Also Read: Tyranny of Numbers: Distribution of 22,102,532 Million Voters in Kenya [FULL LIST]

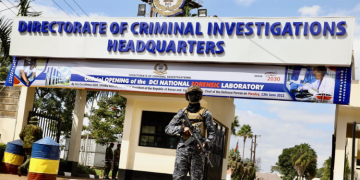

The 2010 Constitution ushered in reform. The discredited commission was replaced by the independent IEBC. New measures, including biometric voter registration, electronic identification at polling stations, and results transmission systems, were introduced to clean the register and enhance transparency.

The voting age was lowered to 18, and diaspora voting was introduced. The system’s strength was tested in 2017 when the Supreme Court nullified the presidential election, a historic global first. Yet, political instability, doubts about the IEBC’s independence, and ethnic politics persist.

The Modern Paradox: Protest vs. Participation

This entire history, the decades of struggle, collides with a modern irony.

In June 2024, Kenyan youth, led by Generation Z, took to the streets to demand better governance, the rule of law, and respect for constitutionalism.

They shook the nation and the world. Yet, when the IEBC launched its subsequent voter registration drive, only a fraction of this energized populace had turned out.

A simple, damning question has been asked: Where are the Gen Z voters?

There is a fundamental disconnect. Governance is ultimately a political process secured at the ballot box.

Protests are vital for applying pressure, but lasting, structural change is enacted by those who win power.

To surrender the voter’s card is to surrender the political future to others. The energy of the streets must be channelled into the polling station.

Why Your Vote Is Decisive

Some argue that one vote is insignificant among millions. History proves this false.

In the 2000 U.S. presidential election, the outcome hinged on a mere 537 votes in the state of Florida. Closer to home, in Kenya’s 2013 election, a shift of just 8,000 votes would have forced a presidential runoff.

In 2022, the presidency was decided by a margin of less than 2%, roughly 200,000 votes out of over 14 million.

Your single vote is amplified within your constituency and county.

In our winner-takes-all system, narrow majorities decide everything from the presidency to the local MCA, which oversees community projects.

When voter turnout is low, as it often is, the power of each individual ballot increases exponentially. Your vote is not just a drop in the ocean; it is the drop that can tip the scale.

How to Be Heard

The path to influence is simple.

Register and Vote: This is the foundational, non-negotiable act of citizenship.

Stay Informed: Follow issues and manifestos, not just political personalities.

Volunteer: Offer your time and skills to candidates and causes you believe in.

Advocate: Use your voice on social media and in your community to shape public opinion.

The right to vote was a prize won from a long and painful struggle. Honouring that history requires more than nostalgia; it demands that we use it.

Follow our WhatsApp Channel and X Account for real-time news updates.