Next to a wall surrounding an empty lot in central Johannesburg, a cherry picker carries a man above the street.

He is not repairing power lines, but instead spray painting a canvas larger than a billboard with portraits of four contemporary South African musicians.

Known as Dbongz, the artist is at the vanguard of a growing movement that has embraced Johannesburg’s grit to create paintings that have helped the once neglected city center spring back to life.

“(The city) used to be dull, mundane and at the same time dodgy,” said the 32-year-old.

“But because of color, because of these lively murals that we paint, people start seeing it as a place they can go into.”

What was an artists’ pastime has increasingly become a business, with real estate firms commissioning artworks to give their buildings a facelift.

In some neighborhoods, walls around every corner have been given a splash of color.

In the 1990s, Johannesburg’s city center notoriously descended into a period of blight and abandonment.

Already hollowed by sanctions in the 1980s, the advent of democracy in 1994 was met with the flight of white-owned businesses to high-walled suburbs.

Entire blocks were left empty. Hotels simply bricked over their doors, without even bothering to auction off the contents.

In the early 2000s, property entrepreneurs returned and started experimenting.

City Property, a real estate firm, bought several abandoned office towers to convert them into affordable housing.

Stuck with an old, tiled wall facing the street, the company commissioned South African artist Hannelie Coetzee to revitalize it.

“Cities are cold, concrete, very gridded-up places. Art brings a bit of a soft edge, or a thought-provoking moment that you might not expect,” she said.

“That for me is the magic thing about public art. It creates meaning through the artists’ voice, for a specific city.”

She created a 166-square-metre portrait of a woman, crafted from more than 2,000 plates, saucers, and bowls.

The woman’s sweep of hair was inspired by how South African women today are adapting traditional hairstyles into trendy new looks.

Developer Adam Levy handed a 10-storey building to American artist Shepard Fairey, best known for his iconic “Hope” portrait of Barack Obama.

An exposed wall became a portrait of Nelson Mandela towering over the city.

Bigger light

Artistic improvements serve as subliminal cues to visitors that someone is caring for the neighborhood, said Levy.

“Now it’s so patently evident that there is a system behind the scenes that cares about what’s going on here. And I think people can open in that space,” Levy said.

“They feel comfortable and safe. They feel well looked after and appreciated.”

Over the past decade, brands have waded into the sector, commissioning murals for advertising purposes, said Marcel Swain, a head of marketing at Heineken South Africa, which recently held a street art competition.

Graffiti artists can be paid thousands of rand for a piece, he said.

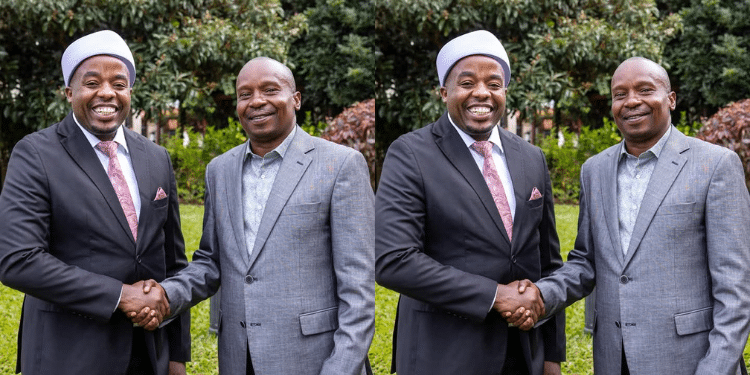

Dbongz has become one of Johannesburg’s most recognizable street artists.

His works have become a visual trademark for the city and have inspired a wave of others.

Dbongz’s latest mural was commissioned by Apple Music to highlight vocalist Simphiwe Dana, folk guitarist Bongeziwe Mabandla, jazz musician Mandisi Dyantyis and amapiano sensation Nobuhle.

The musicians’ faces are painted black and white, but their clothing and jeweler jumps out in vivid colors, against a bright green backdrop in patterns inspired by traditional textiles.

The artwork speaks to another set of portraits of deceased musicians he painted on massive concrete pillars supporting a double-decker highway cutting through the Newtown cultural district.

Born in a township on the western outskirts of the city, the artist is also known for his work in impoverished areas, where he sometimes paints neighborhood children on large walls.

“It gets people to believe in themselves and see themselves in a bigger light, bigger than what it is that’s happening in their lives,” he said.